Understanding and Combating Ableism in Medicine

Understanding and Combating Ableism in Medicine: Promoting Access and Inclusion for Individuals with Disabilities Through Systemic Change

Author(s): Cori Poffenberger MD and Richie Sapp MD MS

Editor: Dina Wallin, MD

Definition(s) of Terms

Disability: American with Disabilities Act (ADA of 1990): The ADA is a law that prevents discrimination against people with disabilities. The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability. The ADA also makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person based on that person’s association with a person with a disability. (Ref.1)

Ableism: Ableism is the intentional or unintentional discrimination or oppression of individuals with disabilities. (Ref.2)

Accessibility: "Accessible" means a person with a disability is afforded the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a person without a disability in an equally effective and equally integrated manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use. The person with a disability must be able to obtain the information as fully, equally and independently as a person without a disability. (Ref.3)

Equity: The quality of being fair, impartial, even, just. (Ref.2)

Disability Humility: Disability humility refers to learning about experiences, cultures, histories, and politics of disability, recognizing that one's knowledge and understanding of disability will always be partial, and acting and judging in light of that fact. (Ref.4)

Inclusion: Inclusion, comparatively, means that all products, services, and societal opportunities and resources are fully accessible, welcoming, functional and usable for as many different types of abilities as reasonably possible. (Ref.2)

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

1 minute presentation

- Define ableism and discuss 1 example of how it manifests in healthcare.

- Discuss the medical vs social models of disability.

- Define disability based on the ADA and discuss who might be covered under this law.

10 minute presentation

- Define and discuss medical vs social models, the ICF, ableism, and representation of providers with disabilities. You could also touch on technical standards.

- Discuss the experience of patients with disabilities in healthcare, with examples of healthcare disparities.

30 minute presentation

- Define and discuss medical vs social models and ableism. Go over ableism examples and microaggressions in detail, utilizing the microaggressions as a leading point for discussion. Utilize the ableist privilege checklist as a pre or post session learning tool.

60 minute presentation

- Discuss definitions, medial and social models, ableism and healthcare disparities for 30-40 minutes, followed by small group discussion for the discussion questions.

- Same as a, but utilize the final 30 minutes for a patient panel with question and answer.

Discussion/Background

Summary

People with disabilities make up a large proportion of our population, but are underrepresented in medicine. This lack of representation is one factor that promulgates an ableist environment in medicine, both for care of patients with disabilities and also for healthcare learners and providers with disabilities. Disability is a frequently overlooked aspect of conversations and strategies aimed at increasing diversity. Healthcare workers with disabilities have a unique perspective, one that provides valuable insight into ways our system promotes marginalization and creates healthcare disparities for those with disabilities. Improving healthcare through systemic change requires listening to and involving individuals with disabilities, both from within healthcare and outside, to promote a more equitable environment, to promote accommodations and universal design, and to dismantle ableism.

Background:

Before discussing ableism in medicine, it is important to have a clear background in the definitions and frameworks used regarding disability. Below we will discuss key definitions, legislation, disability etiquette and best practices, and important frameworks that will frame the discussion as it applies to medicine.

Legal Framework:

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law in 1990. The ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public. The purpose of the law is to make sure that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else. (Ref.5) The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability. The ADA also makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person based on that person’s association with a person with a disability. (Ref.1)

Section 504: The ED Section 504 regulation similarly defines an "individual with handicaps" as any person who (i) has a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities, (ii) has a record of such an impairment, or (iii) is regarded as having such an impairment. The regulation further defines a physical or mental impairment as (A) any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological; musculoskeletal; special sense organs; respiratory, including speech organs; cardiovascular; reproductive; digestive; genitourinary; hemic and lymphatic; skin; and endocrine; or (B) any mental or psychological disorder, such as mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities. The definition does not set forth a list of specific diseases and conditions that constitute physical or mental impairments because of the difficulty of ensuring the comprehensiveness of any such list. (Ref.6)

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA): “The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; PL 101-476), the law governing rights to special education services, defines disability for the purpose of determining who is eligible for special education services (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011) (Ref.7,8):

- Intellectual Disability, hearing impairments (including deafness), speech or language impairments, visual impairments (including blindness), serious emotional disturbance, orthopedic impairments, autism, traumatic brain injury, other health impairments, or specific learning disabilities

- Who, by reason thereof, needs special education and related services.

Types of Disability:

Types of Disabilities and Examples:

- Mobility: Spinal Cord Injuries, Paralysis, Amputation

- Psychiatric: Depression, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia, Post Traumatic Stress

- Auditory: Deaf, Hearing Impaired

- Cognitive/Developmental/Intellectual: Autism Spectrum, Learning Disabilities

- Speech: Speech Impediment, Vocal Paralysis

- Environmental: Allergies, Chemical Sensitivities

- Medical: Impacts from conditions such as Cancer, AIDS, Epilepsy, Asthma, Diabetes, Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), Cystic Fibrosis, Severe Arthritis

Multiple definitions of disabilities exist with some definitions being more encompassing for human rights legislation and some more restrictive when it comes to accessing services.

Accessibility:

“The quality of being possible to get into, use, make use of”. (Ref.2)

"Accessible" means a person with a disability is afforded the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a person without a disability in an equally effective and equally integrated manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use. The person with a disability must be able to obtain the information as fully, equally and independently as a person without a disability. (Ref.3)

Equity:

The quality of being fair, impartial, even, just. (Ref.2) To achieve and sustain equity, it needs to be thought of as a structural and systemic concept. Systemic equity is a complex combination of interrelated elements consciously designed to create, support and sustain social justice. It is a dynamic process that reinforces and replicates equitable ideas, power, resources, strategies, conditions, habits and outcomes. (Ref.9)

Disability Humility:

Disability humility refers to learning about experiences, cultures, histories, and politics of disability, recognizing that one's knowledge and understanding of disability will always be partial, and acting and judging in light of that fact. Disability is a phenomenon with both medical and social components, and clinicians must work to successfully don what philosopher and bioethicist Erik Parens calls a “binocular” view of disability: a view that thoughtfully fuses both medical and social understandings of disability. Without this binocular vision, clinicians will not have the reflective depth necessary to best diagnose, treat, care for, communicate with, and otherwise interact with patients of abilities of all sorts. Without this binocular vision, clinicians will not achieve optimal health outcomes. (Ref.4)

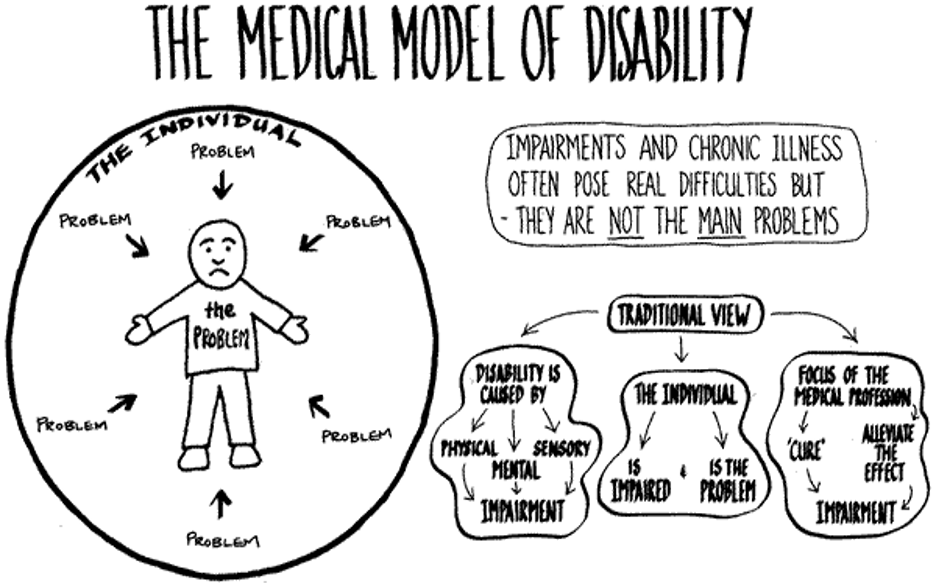

Medical Model of Disability:

The medical model views disability as a feature of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma or other health condition, which requires medical care provided in the form of individual treatment by professionals. Disability, on this model, calls for medical or other treatment or intervention, to 'correct' the problem with the individual. (Ref.10)

(Photo credit (Ref.2): https://www.nccj.org/ableism)

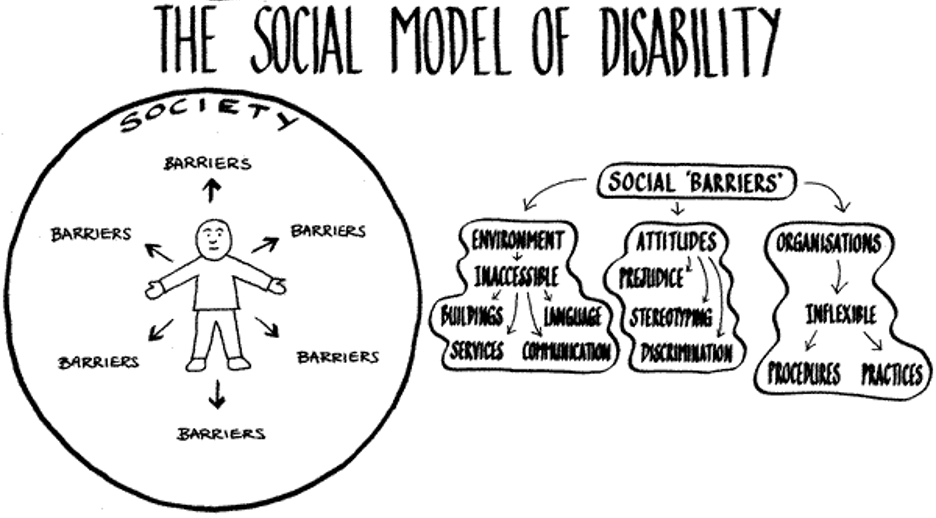

Social Model of Disability:

The social model of disability sees disability as a socially created problem and not at all an attribute of an individual. On the social model, disability demands a political response, since the problem is created by an unaccommodating physical environment brought about by attitudes and other features of the social environment. (Ref.10)

(Photo credit to (Ref.2): https://www.nccj.org/ableism)

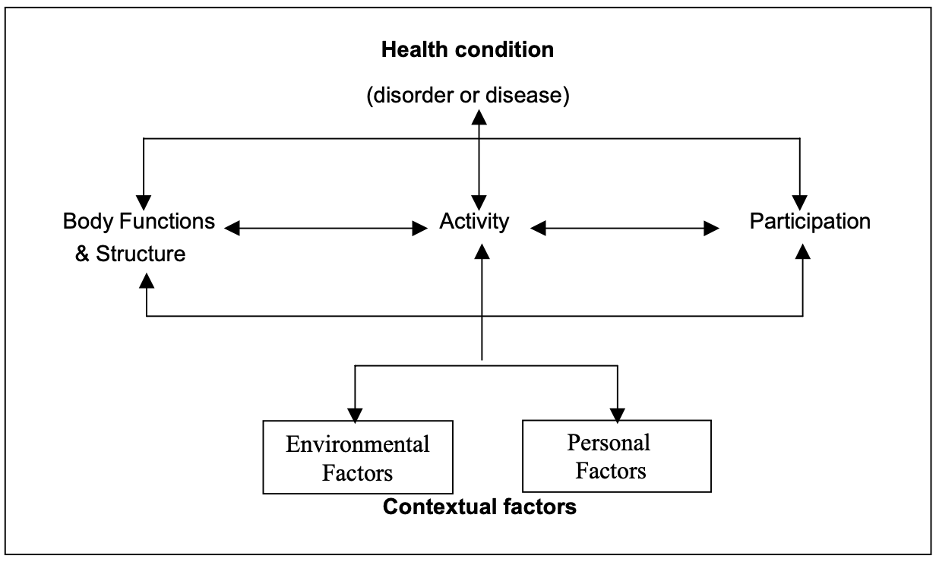

International Classification of Functioning (ICF)

Per the World Health Organization: On their own, neither the social or medical model of disability is adequate, although both are partially valid. Disability is a complex phenomena that is both a problem at the level of a person's body, and a complex and primarily social phenomena. Disability is always an interaction between features of the person and features of the overall context in which the person lives, but some aspects of disability are almost entirely internal to the person, while another aspect is almost entirely external. In other words, both medical and social responses are appropriate to the problems associated with disability; we cannot wholly reject either kind of intervention. A better model of disability, in short, is one that synthesizes what is true in the medical and social models, without making the mistake each makes in reducing the whole, complex notion of disability to one of its aspects. This more useful model of disability might be called the biopsychosocial model. ICF is based on this model, an integration of medical and social. ICF provides, by this synthesis, a coherent view of different perspectives of health: biological, individual and social. (Ref.10) The following diagram is one representation of the model of disability that is the basis for ICF:

(Photo credit to 10: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf)

Inclusion:

Inclusion means that all products, services, and societal opportunities and resources are fully accessible, welcoming, functional and usable for as many different types of abilities as reasonably possible. (Ref.2)

Inclusion, in relation to persons with disabilities, is defined as including individuals with disabilities in everyday activities and ensuring they have access to resources and opportunities in ways that are similar to their peers without disabilities. Disability rights advocates define true inclusion as results-oriented. To this end, communities, businesses, and other groups and organizations are considered inclusive if people with disabilities do not face barriers to participation and have equal access to opportunities and resources.

Common barriers to full social and economic inclusion of persons with disabilities include inaccessible physical environments and methods of public transportation, lack of assistive devices and technologies, non-adapted means of communication, gaps in service delivery, discriminatory prejudice and stigma in society, and systems and policies that are either non-existent or that hinder the involvement of all people with a disability in all areas of life.

Inclusion advocates argue that one of the key barriers to inclusion is ultimately the medical model of disability, which supposes that a disability inherently reduces the individual's quality of life and aims to use medical intervention to diminish or correct the disability. Interventions focus on physical and/or mental therapies, medications, surgeries, and assistive devices. Inclusion advocates, who generally adhere to the social model of disability, allege that this approach is wrong and that those who have physical, sensory, intellectual, and/or developmental impairments have better outcomes if, instead, it isn't assumed that they have a lower quality of life and they are not looked at as though they need to be "fixed", but rather advocates argue to fix abeslist systems, policities, laws and environments. (Ref.2)

Ableism:

Ableism is the intentional or unintentional discrimination or oppression of individuals with disabilities. (Ref.2)

Ableism is any statement or behavior directed at a disabled person that denigrates or assumes a lesser status for the person because of their disability. It includes social habits, practices, regulations, laws, and institutions that operate under the assumption that disabled people are inherently less capable overall, less valuable in society, and/or should have less personal autonomy than is ordinarily granted to people of the same age. (Ref.11)

Ableism is a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other. Ableism is intertwined in our culture, due to many limiting beliefs about what disability does or does not mean, how able-bodied people learn to treat people with disabilities and how we are often not included at the table for key decisions. (Ref.12)

Ableism can take many forms (Ref.13):

- Lack of compliance with disability rights laws like the ADA

- The use of restraint or seclusion as a means of controlling individuals with disabilities

- Segregating adults and children with disabilities in institutions

- Failing to incorporate accessibility into building design plans

- Buildings without braille on signs, elevator buttons, etc.

- Building inaccessible websites

- The assumption that people with disabilities want or need to be ‘fixed’

- Using disability as a punchline, or mocking people with disabilities

- Refusing to provide reasonable accommodations

- The eugenics movement of the early 1900s

- The mass murder of disabled people in Nazi Germany

Minor or every day ableism? (Ref.13)

- Choosing an inaccessible venue for a meeting or event, therefore excluding some participants

- Using someone else’s mobility device as a hand or foot rest

- Framing disability as either tragic or inspirational in news stories, movies, and other popular forms of media

- Casting an actor without a disability to play a disabled character in a play, movie, TV show, or commercial

- Making a movie that doesn’t have audio description or closed captioning

- Using the accessible bathroom stall when you are able to use the non-accessible stall without pain or risk of injury

- Wearing scented products in a scent-free environment

- Talking to a person with a disability like they are a child, talking about them instead of directly to them, or speaking for them

- Asking invasive questions about the medical history or personal life of someone with a disability

- Assuming people have to have a visible disability to actually be disabled

- Questioning if someone is ‘actually’ disabled, or ‘how much’ they are disabled

- Asking, “How did you become disabled?”

What are ableist microaggressions?

Micro-aggressions are everyday verbal or behavioral expressions that communicate a negative slight or insult in relation to someone’s gender identity, race, sex, disability, etc. (Ref.13) In the case of ableism:

- “That’s so lame.”

- “You are so r**** (R-word).”

- “That guy is crazy.”

- “You’re acting so bi-polar today.”

- “Are you off your meds?”

- “It’s like the blind leading the blind.”

- “My ideas fell on deaf ears.”

- “She’s such a psycho.”

- “I’m super OCD about how I clean my apartment.”

- “Can I pray for you?”

- “I don’t even think of you as disabled.”

Phrases like this imply that a disability makes a person less than, and that disability is bad, negative, a problem to be fixed, rather than a normal, inevitable part of the human experience.

Many people don’t mean to be insulting, and a lot have good intentions, but even well-meant comments and actions can take a serious toll on their recipients.

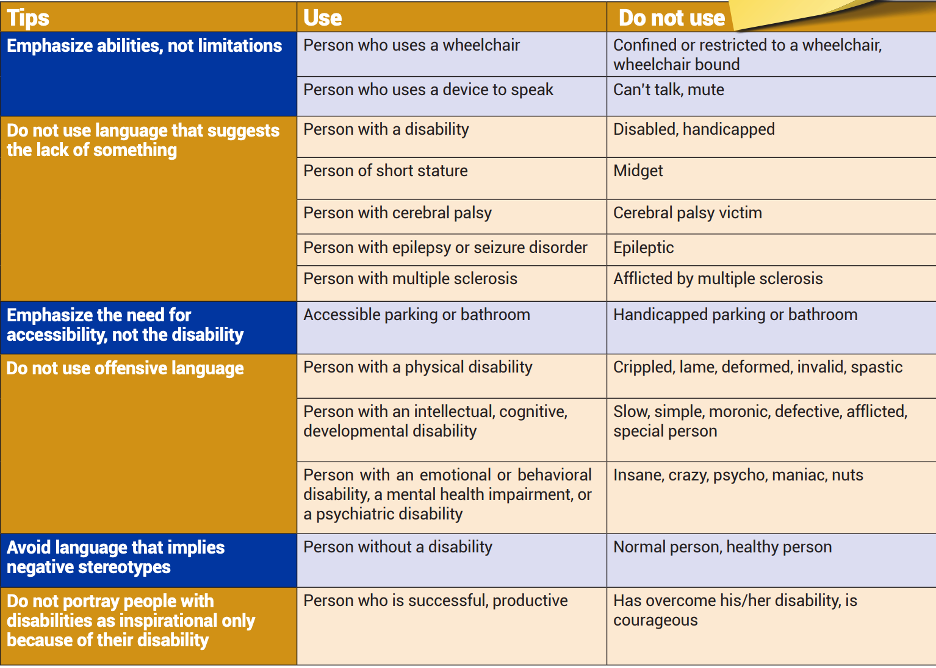

Disability Language

Important Do’s and Don’ts (Ref.14-17):

- Recognize obviously insulting terms and stop using or tolerating them.

- Aim to be factual, descriptive, and simple, not condescending, sentimental, or awkward.

- Respect disabled people’s actual language preferences.

People-first language is based on the idea that the person is not identified by their disability. An example of this is "People who are blind" instead of "Blind people."

Identity-first language means that the person feels that the disability is a strong part of who they are and they are proud of their disability. For example "Disabled person," versus "person who has a disability."

Ultimately, people with disabilities decide how their disability should be stated. Some may choose people first language, while others use identity first language. At this time, people-first language is recommended for use by anyone who doesn't have a disability and for professionals who are writing or speaking about people with disabilities.

Language is dynamic and nuanced, changing at a rapid pace along with social norms, perceptions, and opportunities for inclusion.

CDC language guide (Ref.14):

- People-first language is the best place to start when talking to a person with a disability.

- If you are unsure, ask the person how he or she would like to be described.

- It is important to remember that preferences can vary.

(Photo credit to Ref.14): https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/materials/factsheets/fs-communicating-with-people.html)

When writing about disability (Ref.16):

- Refer to a disability only when it’s relevant to the story and, when possible, confirm the diagnosis with a reputable source, such as a medical professional or other licensed professional.

- When possible, ask sources how they would like to be described. If the source is not available or unable to communicate, ask a trusted family member, advocate, medical professional or relevant organization that represents people with disabilities.

- Avoid made-up words like “diversability” and “handicapable” unless using them in direct quotes or to refer to a movement or organization.

- Be sensitive when using words like “disorder,” “impairment,” “abnormality” and “special” to describe the nature of a disability. The word “condition” is often a good substitute that avoids judgment. But note that there is no universal agreement on the use of these terms — not even close. “Disorder” is ubiquitous when it comes to medical references; and the same is true for “special” when used in “special education,” so there may be times when it’s appropriate to use them. But proceed with extra caution.

- Similarly, there is not really a good way to describe the nature of a condition. As you’ll see below, “high functioning” and “low functioning” are considered offensive. “Severe” implies judgment; “significant” might be better. Again, proceed with caution.

Discussion

People with disabilities make up a large proportion of our patient population but are underrepresented in the physician workforce. One in four (61 million) U.S. adults reported having a disability (Ref.18), however, only 4.6% of medical students, 4.02% of EM residents, and 3.1% of practicing physicians reported having a disability. (Ref.19,20) These numbers are likely underestimated due to the barriers to disclosing a disability in the medical profession. Disability is defined by a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. People with disabilities are a heterogenous group with a variety of different disabilities, both visible and invisible, acquired vs developmental, and have a diverse set of experiences.

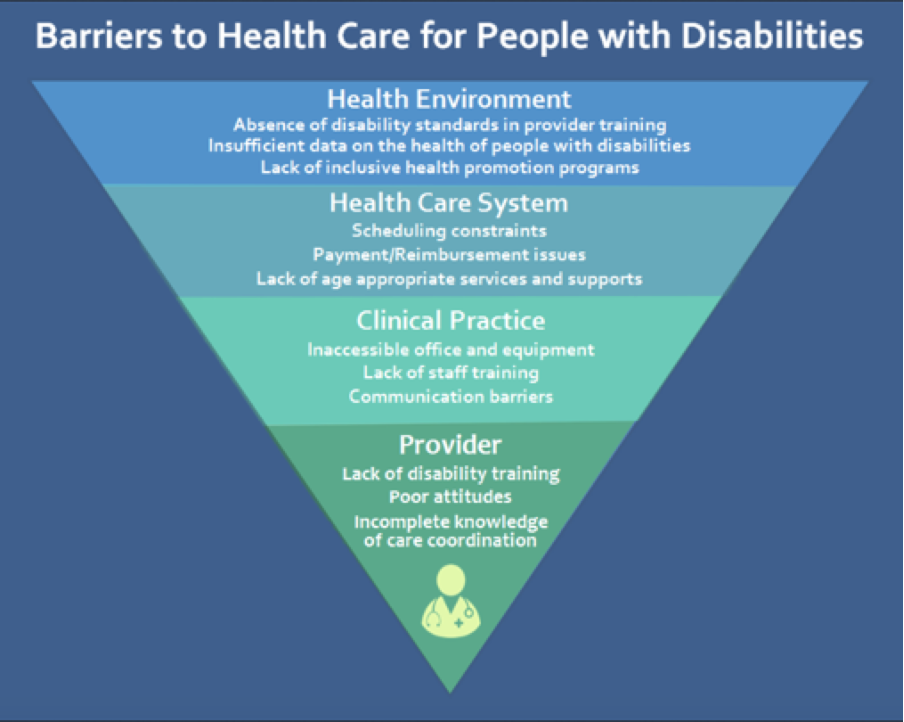

From the patient perspective, individuals with disabilities experience significant health disparities resulting from structural and socioeconomic barriers to health care. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 33% of Americans with a disability do not have a primary care provider, and 25% did not have a routine health examination in the past year (Ref.21). They are also more likely to experience violence or sexual assault and have increased rates of chronic illness and are more likely to develop chronic illness at an early age. Individuals with disabilities face difficulties with coordination among providers, challenges with insurance coverage, and report higher levels of unmet health care needs. As a result, many individuals with disabilities avoid medical treatment and report difficulty finding providers with whom they are comfortable. There are many barriers to health care for people with disabilities from issues with the health environment, health care system, within clinical practice and at provider level. There is also a lack of research about people with disabilities in health care and there is a lack of disability standards in provider training. There are barriers with providing accommodations in scheduling or physical spaces in hospitals and clinics and issues with accessibility for communication or with physical exams. At the individual level, there are biases towards individuals with disabilities on the individual and societal level. (Ref.21)

(Photo credit: Ref.14)

Ableism is discrimination and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that those with typical abilities are superior. At its heart, ableism is rooted in the assumption that disabled people require ‘fixing’ and defines people by their disability. In medicine, ableism can affect patient care when assumptions are made about patient quality of life. In a recent study, 82.4 percent of physicians reported that people with significant disability have worse quality of life than nondisabled people, even though people with disabilities state overall that they have a good quality of life (Ref.22). This idea is known as the disability paradox. One way for individuals to evaluate their inherent implicit bias towards disability is to take the Implicit Bias test from Harvard on Disability to self-reflect on your internal bias (Ref.23) (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html) and review an ableist privilege checklist, which is below.

Ableist Privilege Checklist (Ref.24):

The following activity was originally developed by Lydia X. Z. Brown, a disability justice writer and activist. The text was adjusted by Leora Morinis, Hannah Borowsky, and Dr. Megha Garg for a medical school session.

The checklist we are about to read is meant to serve as an educational tool to help people with and without disabilities become more aware of everyday interactions or observances that are impacted by ableism. Ableism is an entire way of thinking and doing that harms disabled people by treating some types of bodies and minds as valuable, worthy, and desirable, and others as undesirable and unworthy. Ableism is embedded in legal, social, and political institutions, as well as in commonly accepted and unquestioned attitudes and assumptions.

Like all examinations of privilege, this abled privilege checklist is limited. Even if you don’t have a disability, you might not experience some forms of privilege described on this list because of another identity or experience you have. Likewise, even if you do have a disability, you might still experience some forms of privilege described on this list because you don’t have another type of disability. This checklist is not meant to be exhaustive or complete, but rather to give a good and meaningful overview of a variety of disability experiences marked by ableism. In particular, this checklist is meant to help non- disabled people gain more critical consciousness of how ableism systematically advantages and values certain types of bodies and minds in the most ordinary ways, at the expense of others.

We begin this activity with a brief reflection to keep in mind (excerpted from “Understanding Privilege” by Bev Harp):

Privilege is not your fault. It is an artifact of systems that favor some people over others, systems that have evolved naturally to meet the needs of the majority, but have failed to provide adequate accommodations for those outside it.

Privilege is not, in itself, a terrible thing. Having any form of privilege does not make you a bad person. Just about everyone has some form of privilege. No, that doesn’t mean it all somehow “balances out.” A person can have, for example, white privilege, male privilege, heterosexual privilege, and able-bodied privilege without having class privilege. Other forms of privilege can act as a cushion against many of the harsher realities endured by those who belong to multiple disenfranchised groups.

The statement that privilege exists is not an accusation or attempt to blame. It is an invitation to see your experiences and the experiences of others in a new light. It is not an admonition to change the world, but a simple tool with which to begin considering if, possibly, some changes might be worth working toward.

Abled Privilege Checklist:

Instructions: As you read through this list, notice which statements stand out to you. Consider which of these statements apply to you, to people you know, or to patients you have met. Which statements have you previously considered and which introduce unfamiliar concepts?

- Strangers talk directly to me, and not to whoever happens to be with me, because they assume that I am capable of understanding and responding.

- I can choose to sit where I want when I go out to an event, restaurant, movie theater, or religious service.

- I'm not considered a burden on my family or society for being born.

- Strangers will generally not ask me very personal, invasive medical questions. If they do, they are considered rude and their questions are considered inappropriate and embarrassing.

- I don't have to educate every new doctor or health care provider about how my brain or body works.

- My type of body or brain is not used as a metaphor for brokenness, suffering, mediocrity, or ignorance.

- When I get grades from a class, they represent how hard I worked, and not whether or not I had accessible exams, instruction methods that work with my brain, or assignments that I was capable of doing.

- I don't have to worry that my body movements will result in being beaten, tasered, or arrested by the police, especially if I am also white.

- If I decide not to have children, no one will assume that my brain or body must be the reason why; if I do have children, people won't question whether it was responsible or ethical to add another person to the world who might end up being like me.

- I don't have to worry about a job interviewer's reaction to the way I talk or move, or to my adaptive equipment or service animal.

- If I don't have a college education, people won't assume that it's solely because of my brain or body.

- When someone says that all they want is a “healthy” baby, I know they mean a baby whose brain or body will be like mine.

- If I want therapy from a psychologist, licensed social worker, or other counselor, I know I can find therapists whose brains or bodies are like mine, or who at least understand people with brains and bodies like mine.

- People assume that I am able to have and express romantic and sexual desire.

- I don't have to worry about being sent to an institution or having my legal and political rights taken away when I would otherwise become of age to be a legal adult.

- I don't have to choose between working to earn and save money and keeping my life-sustaining supportive services.

- I will not be left to die in the hospital from treatable conditions like pneumonia because of negative assumptions about my quality of life, or a belief that I would be better off dead.

- If I become street homeless, I can go into any shelter or housing services agency, and can expect their building and services to be accessible to me.

- When I’m using the internet, I can access all of the material on most websites.

- People don't ignore me or act nervous because of how I communicate. They will also generally be able to communicate directly with me in the same way that I communicate.

- If the power goes out, I can still breathe.

- If I make a mistake, other people won't use it against all other people with brains or bodies like mine.

Inclusion advocates argue that one of the most significant barriers to inclusion is the medical model of disability, which supposes that a disability inherently reduces the individual's quality of life and aims to use medical intervention to diminish or correct the disability. Interventions focus on physical and/or mental therapies, medications, surgeries, and assistive devices. Inclusion advocates, who generally adhere to the social model of disability, allege that this approach is wrong and that those who have physical, sensory, intellectual, and/or developmental impairments have better outcomes if, instead, it isn't assumed that they have a lower quality of life and they are not looked at as though they need to be "fixed–” rather, the ableist system is what needs change. Physicians have responsibilities towards the disability community that include: 1) responsibility to develop disability humility, 2) responsibility to communicate better with and about patients with disabilities and 3) responsibilities to recognize the authority of people with disabilities as experts about their own lives and communities and to elevate their voices.4 On point three, it is vital to include people with disabilities in curricular development, policy reform, and as a part of the medical profession.

Ableism extends not only toward patient care, it also affects how we think of the inclusion of individuals with disabilities as providers in the medical profession. People with disabilities are vastly underrepresented as healthcare providers. One of the biggest barriers for individuals with disabilities to become physicians are technical standards on entry into medical school. These standards derive from an approach first promulgated in 1979 and have since remained largely unaltered. In 1979, an AAMC Special Advisory Panel on Technical Standards proposed a 5-part categorization of the technical standards that medical schools should require for admission: intellectual–conceptual abilities, behavioral and social attributes, communication, observation, and motor capabilities. Many medical schools’ technical standards do not explicitly support accommodating disability, and focus on incapacity rather than on preserved capacity (Ref.25). During the initial creation of these standards, there was a largely unspoken idea of the “undifferentiated physician”, where all medical students would be able to practice any medical specialty upon graduation, which imposes a standard any student might have difficulty meeting. Another obstacle that was historically an issue for applicants with disabilities getting into medical school was the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), which until March of 2015 included an asterisk on the exam for students who utilized an accommodation for the test.

The technical standards currently in use at most US medical schools are now at odds with both the changes occurring since the 1990 enactment of broad civil rights protections for people with disability (Americans with Disabilities Act; ADA) and the current aspirations for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the medical profession (Ref.26). Only 4.6% of medical students in 2019 report having a disability (Ref.19). There is a push to change these technical standards to focus more on “what” students must demonstrate rather than on “how” they must demonstrate it. In addition, when referencing skills based on the physical attributes of candidates, there is a shift to utilizing a functional approach, and allowing candidates to “provide or direct” medical care (Ref.27). Another barrier to inclusion for healthcare providers with disabilities is the process of obtaining medical licensure. Many state licensing forms require applicants to answer questions regarding mental health, even though there is no evidence that mental health affects patient safety or quality of care (Ref.28).

Medical schools and residency programs should be more proactive in discussing disability throughout aspects of the interview process and when applicants are enrolled. For example, Rush University Medical College has been proactive about changing their technical standards to become more inclusive, which is highlighted below:

“Rush University is committed to diversity and to attracting and educating students who will make the population of health care professionals representative of the national population…actively collaborates with students to develop innovative ways to ensure accessibility and creates a respectful accountable culture through our confidential and specialized disability support…committed to excellence in accessibility; we encourage students with disabilities to disclose and seek accommodations.” (Ref.29)

We recommend that residency programs clearly identify a person not involved with recruitment to confidentially answer applicants' questions about accommodations. Once individuals are in programs, it is important to reach out proactively to ask trainees what accommodations may be needed.

Ableism is not only from the medical profession towards individuals with disabilities, but stigma also can be from the patient toward the provider with a disability. Cheri A Blauwet expresses some of her viewpoints in the following articles: I Use a Wheelchair. And Yes, I’m Your Doctor (Ref.30) and Are you my doctor? (Ref.31) Based on the survey showing doctors perceiving individuals with disabilities with a worse quality of life, perceptions of ableism can be between medical professional colleagues as well as highlighted in the following article: The disabled doctors not believed by their colleagues (Ref.32).

Historically, disability has not been included as a diversity characteristic amongst under-represented groups, which is likely due to the entrenchment of the medical model of disability in medicine. Recently, there has been the formation of medical student groups highlighting disability such as Medical Students with Disability and Chronic Illnesses (https://msdci.org/join-our-movement/) (Ref.33) and groups promoting equity and inclusion amongst residents and faculty such as: Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability, Inclusion and Equity (https://med.stanford.edu/smadie.html) (Ref.34), MDisability (https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability) (Ref.35), #docswithdisabilities podcast (https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability/transforming-medical-education/docs-disabilities-podcast) (Ref.36), and Society for Physicians with Disabilities (https://www.physicianswithdisabilities.org/) (Ref.37).Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of note

1 in 4 (61 millions) US adults report having a disability. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3 (Ref.18)

In 2019, 4.6% of medical students reported disabilities, this is an increase from 2.7%. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.15372 (Ref.19)

This study used a representative sample of 6000 physicians, 178 of whom (3.1%; 95% CI, 2.6%-3.5%) self-identified as having a disability.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1254 (Ref.20)

In 2012, people with disabilities were about two times as likely to visit the ED compared to people without disabilities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.03.001 (Ref.38)

People with disabilities accounted for almost 40 percent of the annual visits made to U.S. EDs each year. Three key factors affect their ED use: access to regular medical care (including prescription medications), disability status, and the complexity of individuals' health profiles.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12025 (Ref.39)

43% of EM residency program directors who responded to the survey included disability-specific content in their residency curricula for an average of 1.5 total hours annually, in contrast to average desired hours of 4.16 hours. Reported barriers to disability health education included lack of time and lack of faculty expertise. A minority of residency programs have faculty members (13.5%) or residents (26%) with disclosed disabilities. The prevalence of EM residents with disabilities was 4.02%. Programs with residents with disabilities reported more hours devoted to disability curricula (5 hours vs 1.54 hours, p = 0.017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10511 (Ref.40)

The ADA mandates that patients with disabilities receive reasonable accommodations. In Iezzoni et al., survey of 714 US physicians in outpatient practices, 35.8 percent reported knowing little or nothing about their legal responsibilities under the ADA, 71.2 percent answered incorrectly about who determines reasonable accommodations, 20.5 percent did not correctly identify who pays for these accommodations, and 68.4 felt that they were at risk for ADA lawsuits. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01136 (Ref.41)

In Iezzoni et al., of 714 practicing US physicians nationwide, 82.4 percent reported that people with significant disability have worse quality of life than nondisabled people. Only 40.7 percent of physicians were very confident about their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disability, just 56.5 percent strongly agreed that they welcomed patients with disability into their practices, and 18.1 percent strongly agreed that the health care system often treats these patients unfairly. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452 (Ref.22)

Slide Presentation or Images

Slides (feel free to utilize and edit these slides as needed):

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1z5_KlZJ6ErdATkBD0VUgOfCweQhMRtwVmuskDNxNSF4/edit?usp=sharing

Role-playing Scenario

Joanna (they/them) is a fourth-year medical student with type I diabetes, who needs frequent opportunities to check and manage their blood sugar. Their Office of Accessible Education accommodations letter specifies that they can take frequent bio breaks without specifying why they need them. Joanna is about to start their ICU rotation. You are the attending on service for Joanna’s first week. How would you best provide an inclusive and supportive learning environment for the team? What do you anticipate the barriers or challenges might be?

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

- Does including individuals with disabilities as healthcare providers weaken our standards and/or the healthcare team? Aren’t people with disabilities less able to do the job?

The medicalization of disability in our society, and of course especially amongst those who are responsible for providing medical care for people with disabilities, results in ableism and the idea that people with disabilities are “less than.” Combatting this idea requires analyzing our understanding of disability and challenging ourselves to incorporate a social model approach. If we design our systems in a way that promotes access and inclusion for all, then people with disabilities are able to do the functions of the job just as well as those without disabilities. This requires flexibility and dismantling our often rigid adherence to doing things the way they have always done.

Disabled Doctors Were Called Too ‘Weak’ To Be In Medicine. It’s Hurting The Entire System. (Ref.42) https://www.huffpost.com/entry/disabled-doctors-medicine-ableism_n_60f86967e4b0ca689fa560dc

- Isn’t it good to “fix” differences to help individuals with disabilities function better in the world?

The answer to this is situation dependent. It depends on what the individual wants, and how those “fixes” will improve function. The important thing is that the focus should be on function and on the voiced needs of the individual with disability, rather than on making the individual more like those without disabilities just for the sake of helping them to “fit in.”

- I find individuals with disabilities in healthcare so inspirational–I am impressed they are able to be successful given all they suffer. Should I tell them that?

Ethical Issues

Physicians with disabilities in Medicine:

Physicians with disabilities have often been barred from partaking in medicine due to technical standards in medical school admission processes. When technical standards were created, they focused on a specific set of abilities and attributes that needed to be obtained by graduation to become a doctor in any residency field. Additionally, medical schools and residency programs have been ill-equipped to provide accommodations for individuals with disabilities once they reach that stage in training. Licensure applications ask questions regarding mental health and disabilities. The creation of these processes with the medical model of disability are ableist as they were created without inclusion of individuals with disabilities who may need accommodations, but can perform at the same level as any other individual.

Patient Care:

Despite the growing understanding that disability is a normal part of the human experience, the lives of persons with disabilities continue to be devalued in medical decision-making. Negative biases and inaccurate assumptions about the quality of life of a person with a disability are pervasive in U.S. society and can result in the devaluation and disparate treatment of people with disabilities, and in the medical context, these biases can have serious and even deadly consequences. The National Council on Disability has published reports (https://ncd.gov/publications/2019/bioethics-report-series) (Ref.45) exploring how people with disabilities are impacted by biases and assumptions in some of the most critical healthcare issues we face, including (Ref.45):

- Organ transplantation

- Physician-assisted suicide

- Genetic testing

- Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)

- Medical futility

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities:

“52 percent of people with disabilities who requested a referral to a specialist regarding an organ transplant evaluation actually received a referral, while 35 percent of those “for whom a transplant had been suggested” never even received an evaluation.” https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Organ_Transplant_508.pdf (Ref.45)

Patients with Disabilities: Avoiding Unconscious Bias When Discussing Goals of Care

False assumptions about patients' quality of life can affect prognosis, the treatment options that we present, and the types of referrals that we offer. Complex disability is sometimes equated with terminal illness. This common confusion can result in premature withdrawal of life-preserving care. (Ref.46)

Medical Futility and Disability Bias:

Over the past three decades, medical futility decisions by healthcare providers—decisions to withhold or withdraw medical care deemed “futile” or “non beneficial”—have increasingly become a subject of bioethical debate and faced heavy scrutiny from members of the disability community. Negative biases and inaccurate assumptions about the quality of life of a person with a disability are pervasive in US society and can result in the devaluation and disparate treatment of people with disabilities. Health care providers are not exempt from these deficit based perspectives, and when they influence a critical care decision, the results can be a deadly form of discrimination (Ref.45). https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Medical_Futility_Report_508.pdfOpportunities

In recent years disability has begun to be considered more as an aspect of diversity.. Recently, there has been formation of medical student groups highlighting disability such as Medical Students with Disability and Chronic Illnesses (https://msdci.org/join-our-movement/) (Ref.33) and groups promoting equity and inclusion amongst residents and faculty including: Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability, Inclusion and Equity (https://med.stanford.edu/smadie.html) (Ref.34), MDisability (https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability) (Ref.35), #docswithdisabilities podcast (https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability/transforming-medical-education/docs-disabilities-podcast)(Ref.36, and Society for Physicians with Disabilities (https://www.physicianswithdisabilities.org/).(Ref.37)

The percentage of medical students identifying as having disabilities increased from 2.7% in 2016 to 4.6% in 2019 (Ref.19). Rather than routinely excluding persons with disabilities, more research is needed into including people with disabilities as a unique and important population in healthcare. A recent article reported the number of physicians with disabilities in healthcare as 3.1% (Ref.20). A call to action paper in AEM Education and Training highlights the current state of disability education in emergency medicine residency training, and offers suggestions for improvement, including: designing curriculum using cultural humility, integrating disability into existing curricular and EM milestones, and engaging the disability community outside and within training programs (Ref.21).

Welcoming disability as an aspect of identity and diversity, and providing accommodations, is beneficial to all health care professionals regardless of ability, as this combats the toxic culture of strength in medicine. This culture is harmful to all who work in the healthcare system. Traditionally healthcare providers have been discouraged from taking care of personal healthcare needs, sacrificing all for the good of their patients or the system in general. Creating a culture that is supportive of accomodations, one where all who work in healthcare are encouraged to address their physical and emotional needs, promotes an equitable and inclusive environment for all that will reduce burnout and promote sustainability.

Through the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM), there is a group that focuses on disability rights and issues called the Accommodations Committee. Their mission statement is: The ADIEM Accommodations Committee shares the belief that all people have the right to accessible medical care and health care training. It seeks to promote physician delivery of equitable care regardless of a patient’s disability (physical, mental/cognitive, emotional) or cultural/linguistic discordance. The committee also seeks to promote accommodations for health care providers with disabilities. https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies/adiemnew/about/adiem-committees/accommodations (Ref.47)Journal Club Article links

- Commentary article: the authors review the state of disability in medical education and training, summarize key findings from an Association of American Medical Colleges special report on disability, and discuss considerations for medical educators to improve inclusion, including emerging technologies that can enhance access for students with disabilities. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2018/04000/Removing_Barriers_and_Facilitating_Access_.27.aspx?casa_token=AZID1fVHNV0AAAAA:WRY2-FpoMBF398_OeEV1dcHyKo7M7hpWKYYz0TJs2e1_rTx_xH7lpw1GsYGhLL_p9MGNNo6gA0mltPYfuu1da2I (Ref.48)

- The ACGME updated the common core requirements for graduate medical education (GME) programs in 2019 to include a new provision, “The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must engage in practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents.” To meet this common core requirement, GME programs must create inclusive policies and practices, understand their responsibilities under federal law, and educate themselves regarding reasonable accommodations for learners with disabilities. This article reviews the systemic barriers in GME for residents with disabilities and discusses mechanisms to reframe those barriers as opportunities to build programs that are more inclusive. It is a good starting point for GME programs that seek to include disability as an aspect of diversity in their program. https://meridian.allenpress.com/jgme/article/11/5/498/421201/Realizing-a-Diverse-and-Inclusive-Workforce-Equal (Ref.49)

- This report by the AAMC captures the day-to-day experiences of learners and academic medicine physicians with disabilities. By bringing these important voices into the discussion and sharing their lived experiences, this report elucidates the challenges and complexities encountered by these members of the academic medicine community. https://sds.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra2986/f/aamc-ucsf-disability-special-report-accessible.pdf (Ref.50)

- This EM paper reviews the current state of health care for patients with disabilities and the current state of undergraduate and graduate medical education on the care of patients with disabilities, then provides suggestions for an improved EM residency curriculum that includes education on the care for patients with disabilities. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7592824/ (Ref.21)

- Survey study of Emergency Medicine program directors looking at the current state of disability health education in EM residency programs, as well as the prevalence of residents and faculty with disabilities. Also looks at the association of residents or faculty with disabilities with likelihood of providing education on disability in residency. Good article to start discussion regarding practices for recruitment and retention, as well as review of the curricula regarding diversity topics. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10511 (Ref.40)

Discussion Questions

- What are the barriers for individuals with disabilities to becoming physicians or other healthcare providers?

- How can programs better promote disability as diversity?

- What are examples of ableism within the healthcare system for healthcare providers? For patients? How would you be able to mitigate and improve these institutional problems?

Summary/Take-home Themes

- Disability is a frequently overlooked aspect of programs that seek to increase diversity. As with other marginalized identities, the belonging of people with disabilities within healthcare makes our teams stronger. Healthcare providers with disabilities have a unique perspective that provides valuable insight into the ways in which our system promotes marginalization and healthcare disparities for disabled patients.

- Like forms of oppression, ableism, or discrimination against disabled people, is codified in the systems and structures that have been put into place in our society. In order to combat ableism, we need to look at the policies and procedures we have put in place that limit the participation of people with disabilities in healthcare.

- Disability is itself diverse, encompassing a variety of differences or impairments. There is no one size fits all to access. The key is to listen to disabled people, and to promote universal design as a way to improve the system for all.

Specialty Resource links

- This EM paper reviews the current state of health care for patients with disabilities and the current state of undergraduate and graduate medical education on the care of patients with disabilities, then provides suggestions for an improved EM residency curriculum that includes education on the care for patients with disabilities. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7592824/ (Ref.21)

- Survey study of Emergency Medicine program directors looking at the current state of disability health education in EM residency programs, as well as the incidence of residents and faculty with disabilities. Also looks at the association of residents or faculty with disabilities with likelihood of providing education on disability in residency. Good article to start discussion regarding practices for recruitment and retention, as well as review of the curricula regarding diversity topics. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10511 (Ref.40)

Video Links

Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution

Film: https://www.netflix.com/title/81001496#:~:text=Watch%20Crip%20Camp%3A%20A%20Disability%20Revolution%20%7C%20Netflix%20Official%20Site (Ref.51)

Discussion Guide: https://2t3wvj1gyj7x2wglr2wrwsaa-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Crip-Camp_Discussion-Guide.pdf (Ref.51)

Doctors with Disabilities: Perseverance in Practice

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X71TP7hitlo (Ref.52)

Disability Does Not Equal Inability

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r81WpiPUMYs (Ref.53)

Quiz Questions/Answers

- In the United States, what is the percentage of people with disabilities?

- 10 to 15% of the population

- 20 to 25% of the population

- 30 to 40% of the population

- 50 to 60% of the population

- How does the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) define a person with a disability?

- A person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.

- A person who is unable to do any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment

- A person, due to illness or injury, either physical or mental, prevents them from performing their regular and customary work.

- A person with any condition of the body or mind parent impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).

- Regarding accommodations, which of the following is not true?

- When judging students' competency, we should concentrate on the "what", not the "how." In other words, allowing students to satisfy objectives in a variety of ways, depending on their disability

- In the clinical setting, accommodations may include bio breaks, schedule modifications, and time off for appointments

- They are rights under the law, not special privileges

- If they are given to one person on a team, they must be given to everyone, regardless of disability status, in order to satisfy human resources equitable treatment mandates

- Regarding students with disabilities, which of the following is true? (select all that apply)

- We should screen them out in the admissions process in order to avoid future conflict over clinical accommodations.

- They often work harder than their peers to manage the dual responsibilities of their health and education

- They need accommodations to have equal access to programs, but do not want a less rigorous educational experience

- Their dual role as patients and future providers is a conflict of interest that must be disclosed

- Which of the following is the correct way to refer to a learner with a disability?

- Person-first language (person with a disability)

- Identity first language (disabled person)

- Depends on the individual

- Which of the following is the appropriate term when referring to someone in a wheelchair?

- A person who uses a wheelchair

- a wheelchair-bound person

- a handicapped person

- a person confined to a wheelchair

Answer Key

Answer: B, While 20-25% of the US population has a condition that could qualify as a disability, only around 5% of medical students and 3% of practicing physicians disclose a disability. These numbers are likely underreported due to stigma around disclosure and barriers to entry into the medical profession.

Answer: A, American with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) is a piece of human rights legislation that has a broad definition of disability, and prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities. “Learning” is considered a major life activity. B is the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) definition. C is the paraphrased definition of the California Employment Development Department for disability insurance benefits. D is the paraphrased medical definition defined by the CDC

Answer: D, Providing accommodations is about providing equity to individuals with disabilities as the way society is structured is the root cause of disability. Equity recognizes that people with disabilities need support to perform the essential duties of their jobs, and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed for each individual. Accommodations are not special privileges, but rather the legal right of people with disabilities.

Answer: B and C, Depending on the effort required to manage a disability and chronic illness, it can be like having a second job. A is illegal. D is incorrect. Having the dual role gives one important insight into the minds of both physicians and patients. It is not a conflict of interest.

Answer: C, Individuals vary on whether they like to be referred to as a “person with a disability” or a “disabled person”. Person first language highlights that disability is only one aspect of their identity. Identity first language highlights that their disability is inherent to their identity, not just something they have.

Answer: A, A person who uses a wheelchair is not bound to it, nor confined to it. A wheelchair is an assistive device. The term "handicapped" is no longer considered appropriate. A "person with a disability" or "disabled person" are the appropriate termsCall to Action Prompt

Reference

- What is the definition of disability under the Ada? ADA National Network. (2022, March 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://adata.org/faq/what-definition-disability-under-ada

- Ableism. NCCJ. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.nccj.org/ableism

- Understanding accessibility. Accessibility. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://accessibility.iu.edu/understanding-accessibility/index.html

- Reynolds J. M. (2018). Three Things Clinicians Should Know About Disability. AMA journal of ethics, 20(12), E1181–E1187. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2018.1181

- An overview of the Americans with disabilities act. ADA National Network. (2022, March 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://adata.org/factsheet/ADA-overview

- US Department of Education (ED). (2020, January 10). The civil rights of students with Hidden Disabilities and Section 504. Home. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq5269.html#:~:text=DISABILITIES%20COVERED%20UNDER%20SECTION%20504,as%20having%20such%20an%20impairment

- Sec. 300.8 child with a disability. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2018, May 25). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8

- About idea. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2022, February 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020, August 25). Equity vs. equality and other racial justice definitions. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.aecf.org/blog/racial-justice-definitions

- ICF beginners guide - who | world health organization. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). Words matter, and it's time to explore the meaning of "ableism.". Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2020/10/25/words-matter-and-its-time-to-explore-the-meaning-of-ableism/?sh=1484b878716

- Smith, L. (n.d.). Center for Disability Rights. #Ableism – Center for Disability Rights. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://cdrnys.org/blog/uncategorized/ableism/

- Ableism 101 - what is ableism? what does it look like? Access Living. (2021, January 8). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 1). Communicating with and about people with disabilities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/materials/factsheets/fs-communicating-with-people.html

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). Here are some DOS and don'ts of disability language. Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2020/09/30/here-are-some-dos-and-donts-of-disability-language/?sh=9610b77d1700

- National Center on Disability and journalism. NCDJ. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://ncdj.org/style-guide/

- Disability language guide - disability.stanford.edu. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://disability.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj1401/f/disability-language-guide-stanford.pdf

- Okoro, C. A. (2018). Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care Access by Disability Status and Type Among Adults—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3

- Meeks, L. M., Case, B., Herzer, K., Plegue, M., & Swenor, B. K. (2019). Change in Prevalence of Disabilities and Accommodation Practices Among US Medical Schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA, 322(20), 2022–2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.15372

- Nouri, Z., Dill, M. J., Conrad, S. S., Moreland, C. J., & Meeks, L. M. (2021). Estimated Prevalence of US Physicians With Disabilities. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e211254. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1254

- Rotoli, J., Backster, A., Sapp, R. W., Austin, Z. A., Francois, C., Gurditta, K., Mirus, C., 4th, & McClure Poffenberger, C. (2020). Emergency Medicine Resident Education on Caring for Patients With Disabilities: A Call to Action. AEM education and training, 4(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10453

- Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Donelan, K., Lagu, T., & Campbell, E. G. (2021). Physicians' Perceptions Of People With Disability And Their Health Care. Health affairs (Project Hope), 40(2), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

- Projectimplicit. Take a Test. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

- Borowsky H, Morinis L, Garg M. Disability and Ableism in Medicine: A Curriculum for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17(1):11073. https://doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11073

- DeLisa, J. A., & Lindenthal, J. J. (2016). Learning from Physicians with Disabilities and Their Patients. AMA journal of ethics, 18(10), 1003–1009. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.10.stas1-1610

- Curry, R. H., Meeks, L. M., & Iezzoni, L. I. (2020). Beyond Technical Standards: A Competency-Based Framework for Access and Inclusion in Medical Education. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 95(12S Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments), S109–S112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003686

- Kezar, L. B., Kirschner, K. L., Clinchot, D. M., Laird-Metke, E., Zazove, P., & Curry, R. H. (2019). Leading Practices and Future Directions for Technical Standards in Medical Education. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 94(4), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002517

- Lawson N. D. (2020). Eliminate Mental Health Questions on Applications for Medical Licensure. The American journal of medicine, 133(10), 1118–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.04.011

- Rush Medical College Admissions. Admission Requirements - Doctor of Medicine (MD) Program | Rush University. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.rushu.rush.edu/rush-medical-college/doctor-medicine-md-program/admission-requirements

- Blauwet, C. A. (2017, December 6). I use a wheelchair. and yes, I'm your doctor. The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/06/opinion/doctor-wheelchair-disability.html

- Stanford Medicine. (n.d.). A call for more doctors with disabilities. Stanford Medicine. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://stanmed.stanford.edu/listening/time-that-doctor-with-disability-seen-ordinary.html

- BBC. (2021, April 18). The disabled doctors not believed by their colleagues. BBC News. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/disability-56244376

- Get involved! MSDCI. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://msdci.org/join-our-movement/

- Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity. (n.d.). Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity (Stanford Med Adie). Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://med.stanford.edu/smadie.html

- MDisability: Family medicine: Michigan medicine. Family Medicine. (2021, April 29). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability

- Docs with disabilities podcast: Family medicine: Michigan medicine. Family Medicine. (2022, March 8). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability/transforming-medical-education/docs-disabilities-podcast

- Society for physicians with disabilities. Society for Physicians with Disabilities. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.physicianswithdisabilities.org/

- Kim, A. M., Lee, J. Y., & Kim, J. (2018). Emergency department utilization among people with disabilities in Korea. Disability and health journal, 11(4), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.03.001

- Rasch, E. K., Gulley, S. P., & Chan, L. (2013). Use of emergency departments among working age adults with disabilities: a problem of access and service needs. Health services research, 48(4), 1334–1358. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12025

- Sapp, R. W., Sebok-Syer, S. S., Gisondi, M. A., Rotoli, J. M., Backster, A., & McClure Poffenberger, C. (2020). The Prevalence of Disability Health Training and Residents With Disabilities in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. AEM education and training, 5(2), e10511. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10511

- Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Lagu, T., Pendo, E., & Campbell, E. G. (2022). US Physicians' Knowledge About The Americans With Disabilities Act And Accommodation Of Patients With Disability. Health affairs (Project Hope), 41(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01136

- Lu, W. (2021, August 26). Disabled doctors were called too 'weak' to be in medicine. it's hurting the entire system. HuffPost. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/disabled-doctors-medicine-ableism_n_60f86967e4b0ca689fa560dc

- Young, S. (n.d.). I'm not your inspiration, thank you very much. Stella Young: I'm not your inspiration, thank you very much | TED Talk. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much?language=en

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). How to avoid "inspiration porn". Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2019/11/29/how-to-avoid-inspiration-porn/?sh=4e8cabbe5b3d

- Bioethics and disability report series. NCD.gov. (2022, January 18). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://ncd.gov/publications/2019/bioethics-report-series

- Kripke C. Patients with Disabilities: Avoiding Unconscious Bias When Discussing Goals of Care. American Family Physician. 2017;96(3):192-195. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2017/0801/p192.html

- Accommodations. Default. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies/adiemnew/about/adiem-committees/accommodations

- Meeks, L. M., Herzer, K., & Jain, N. R. (2018). Removing Barriers and Facilitating Access: Increasing the Number of Physicians With Disabilities. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(4), 540–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002112

- Meeks, L. M., Jain, N. R., Moreland, C., Taylor, N., Brookman, J. C., & Fitzsimons, M. (2019). Realizing a Diverse and Inclusive Workforce: Equal Access for Residents With Disabilities. Journal of graduate medical education, 11(5), 498–503. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00286.1

- UCSF Disability Special Report Accessible. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sds.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra2986/f/aamc-ucsf-disability-special-report-accessible.pdf

- Watch Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution | Netflix Official Site. www.netflix.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.netflix.com/title/81001496#:~:text=Watch%20Crip%20Camp%3A%20A%20Disability%20Revolution%20%7C%20Netflix%20Official%20Site

- Doctors With Disabilities: Perseverance in Practice. www.youtube.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X71TP7hitlo

- Disability Does Not Equal Inability. www.youtube.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r81WpiPUMYs