Identity-First Language

What Should I Say? Understanding Person- vs. Identity-First Language

Authors: Adam McFarland, MD, and Mia L. Karamatsu, MD

Editor: Ryan Tsuchida, MD

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

Person-First Language (PFL): puts the person before the disability or illness (i.e. "person with autism" or "person who is deaf")

Identity-First Language (PFL): puts the disability first in the description (i.e. "autistic person" or "deaf person")

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

For a 1-minute presentation: Define both types of identity language with examples. Add the bottom line that when in doubt, just ask.

For a 10-minute presentation: Include a short description of the Sharif et al. article to provide some context and evidence to the discussion of identity language. Alternatively, include a short paired or group discussion on what language the learners use to self-identify and why.

For a 30-minute presentation: In addition to the suggestions for the 10-minute presentation, include a further review of the limited evidence for identity language from sources provided. Additionally, utilize the linked resources and videos for further description to these terms and background knowledge. Include role-playing scenarios or further discussion questions from there.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview of this topic so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

Language gives the individual an opportunity to reinforce their identity unique from dominant cultural groups, but also has the ability to reinforce stigma, otherness, and negative stereotypes of people that can lead to significant consequences on physical and mental health, create and reinforce disparity, and detract from inclusivity. Person-first language puts the person before the disability or condition. For example, a person with autism or a person who is blind. Identity-first language emphasizes the marker of identity a particular group chooses to highlight, for example a "disabled person” rather than “person who is disabled”. Ultimately, the method by which a person chooses to self-identify is up to them and they should have agency to determine their preferred identity language. When in doubt, engage in honest discussion and ask.

The words and phrases used to create and demarcate identity can have significant impact on the experience of personhood of individuals and groups in society. Language gives the individual an opportunity to craft how they are seen in the world, and reinforce or detract from aspects of their identity unique from dominant cultural groups.1,2 Language also has the ability to reinforce stigma, otherness, and negative stereotypes of people that can lead to significant consequences on physical and mental health, create and reinforce disparity, and detract from inclusivity.1-3 Identity- and person-first language provides an opportunity to explore identity, stigma, and personhood for those who belong to non-dominant groups in our society.

Person-first language (PFL) and identity-first language (IFL) are two different methods for describing identity.2 PFL puts the person before the disability or condition, for example saying a person with autism rather than autistic person. IFL therefore emphasizes the identity of the individual, such as describing a disabled person rather than a person with disability. There is debate about whether PFL or IFL should be the dominant method of describing identity, with use varying by setting (e.g. academic writing vs. colloquial conversation) and speaker.1 For example, there is no consensus among the disability community about preferences for person-first versus identity-first language.1,4

Most recently in the academic setting, emphasis has been placed on utilizing PFL in the formal writing and presentation. The American Psychological Association (APA) has previously advocated for PFL in an effort to reduce stigma, prejudice, and stereotypes toward people with disabilities, which has been reflected in the medical field.1,2,4,9-11 Advocates for PFL emphasize that this method of marking identity demarcates the person from their disability or condition, and seeks to reduce objectification of the individual to a particular label.1,2,5 Additionally, they posit that PFL functions as a constructive way to counter negative or ambivalent attitudes toward people with disabilities, noting the impact of language on attitudes and stigma.1,3,9,10 Lastly, PFL attempts to emphasize the individuality that exists within groups. Two people who are blind likely have vastly different lived experiences based on their multiple identities and potential barriers, and the focus on the individual potentially reduces their objectification via a common label.

However, it is important to note that many people with disabilities choose to use IFL to describe themselves.4,6,7 Proponents of IFL posit that this language allows a person to gain control or reclaim their identity rather than let other people or groups name and define them.3,7 In doing so, these individuals protect their autonomy and agency over identity, holding more power over their personhood in the face of dominant cultural groups that have historically oppressed them. Additionally, it can be argued that PFL implies that there is something inherently negative about the disability and unnecessarily dissociates the disability from the person; however, IFL reframes the disability as neutral, positive, or to be celebrated.1,3 A prominent example is in the Deaf community. The self-description of Deaf encompasses a rich cultural group that is considered inseparable from their identity.8 Rather than distancing themselves from the term “deaf”, it is embraced and utilized as an identity marker and cultural group in a way that “person who is deaf” is unable to encompass.8

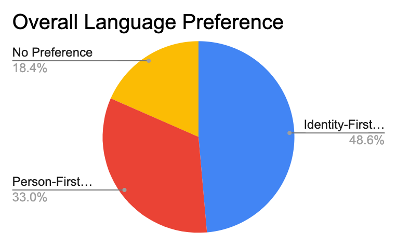

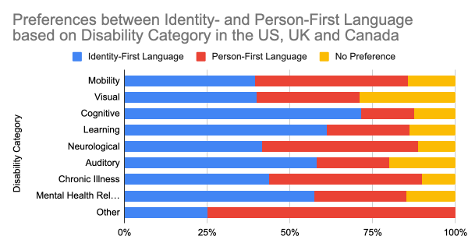

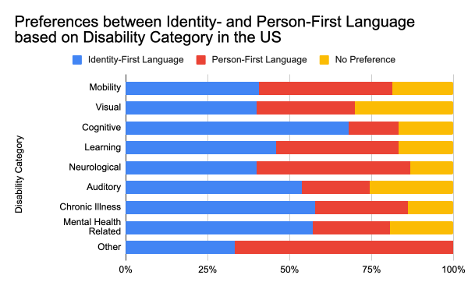

Importantly, the APA and medical literature recognizes that both types of language can be correct.1,7 There are few data that explicitly explore this issue, and certainly could not represent the entirety of the identity diaspora of which identity language could apply. However, these studies show significant variation in preferences. A recent study surveyed 491 disabled people from multiple different disability, gender, age, and nationality groups about their language identity preferences.7 They found that overall 48% of participants preferred IFL, 33% PFL, and 18% no preference.7 However, these preferences varied significantly between different identity groups, suggesting that the approach to language identity must be adaptable and reflective of the preferences of that group.7 Ultimately, individuals have agency to determine their preferred identity language and how they self-identify is up to them.1,4,6,7 When in doubt, engage in earnest and empathetic discussion and ask the individual their language preference.

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of Note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

Few data have been collected on this topic. This article7 is one of the largest and most recent analyses of identity language preferences available in the literature at this time of the development of this curriculum. In this study, the authors report survey results from 491 people from the USA, Canada, and the UK on their identity language preferences.

(Adapted from Sharif et al)

(Adapted from Sharif et al)

The results show that 49% of all disabled people preferred identity-first language whereas 33% preferred person-first language and 18% had no preference. The authors further used a mixed logistic regression model to analyze language preference by disability category, gender, and country, with a secondary analysis specific to participants from the USA as they were the majority of survey respondents.

(Adapted from Sharif et al)

(Adapted from Sharif et al)

(Adapted from Sharif A et al)

Role-Playing Scenarios

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

- A resident is presenting a pediatric patient to you in the patient's room. They begin the presentation with "This is a 16 year old male with autism (substitute term for a different one as desired)..." After the resident is done, the patient tells you "I'm not a person with autism, I'm autistic." What type of identity language is the resident using? The patient? How could the discordance in identity language affect the patient-provider relationship? What discussion would you have with the resident about this situation? What could have been done differently?

- A resident starts a patient presentation with "This is a 23 year old male sickler who presents with chest pain. He is a frequent flier as he is always here for pain meds." What sort of identity language is the resident using? How does the choice of work "sickler" potentially impact the way the resident, attending, or patient navigate the encounter? Does this language introduce bias?

- A new department initiative is implemented that focuses on person-first identity language as the default for all patient interactions and written communication to reduce bias. Do you think this policy would reduce bias? How easy would this be to incorporate into your current practice? What challenges do you see in following these guidelines?

- You receive a phone call from your hospital transfer center. An outside hospital is transferring "a 45 year old morbidly obese alcoholic female with abdominal pain" to your ED because their CT scanner isn't big enough for the patient. Does the identity language used in the prompt influence your initial assumptions about the patient? How would you feel if the patient overheard this phone call? Are there identity terms you use regularly that should be avoided in front of patients? Are there ways in which health care providers force identity language on patients and potentially introduce bias?

Facilitator Guides

- Resident - person-first; Patient - identity-first; discordance could contribute to the patient feeling discriminated against or that provider has an unintentional bias, potentially disrupting trust or truncating patient's desire to interact with provider. It could negatively impact the ability of the resident to take care of the patient appropriately; for discussion with the resident, could ask participants to describe their approach to such a conversation, how they would elicit understanding of language identity, and facilitate a growth opportunity for that resident.

- Consider using strength-based language when describing a patient if appropriate ("patient living with diabetes" vs "patient suffering from diabetes"); respectfully ask patients how they would like to be introduced; the term "sickler" could introduce a label that perpetuates stereotypes and stigmatizes or dehumanizes the patient, potentially affecting patient care or provider perception of that individual.

- No necessarily wrong answers to this question. This scenario attempts to link the idea of identity language to current practice, as well as reflect on the implications of identity- vs. person-first language for providers on patient care.

- When you hear this phone call, do you have any emotional reaction or do you create a specific mental picture of this patient? Consider identity terms we use regularly to label patients (alcoholic, cancer patient). Are there situations in which we project identity and potential bias onto these patients with our word choices? Do you think patients would use these terms to describe their identity? How might that impact patient care?

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (i.e. a white facilitator presenting on antiracism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

Current recommendations from the APA and AMA recommend PFL in academic and formal writing. However, limited evidence seems to suggest a patient preference for IFL, although this can vary by disability identity, gender, age, and other identity markers. When in doubt, open communication and proactive inquiry are best practices.

Opportunities

Sometimes DEI topics can present depressing history and statistics. This section highlights glimmers of hope for the future: exciting projects, areas of study inspired by the topic, or even ironic twists where progress has emerged or may be anticipated in the future.

Opportunities in this topic are abundant as research is scarce and recommendations are often formed by expert opinion rather than hard evidence. In particular, emergency medicine has minimal literature related to identity language preference. Further directions could include how emergency medicine physicians utilize PFL vs. IFL, our patient preferences, and potential impact of language on provider attitudes and patient care.

Journal Club Article Links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

- Does Language Matter? Identity-First Versus Person-First Language Use in Autism Research: A Response to Vivanti. This article highlights key points in the debate surrounding identity vs. person-first language to describe autistic people. A good article for understanding some of the key concepts of identity language, its impact on identity groups, and a discussion of best practices.

- Among Emergency Physicians, Use of the Term “Sickler” is Associated with Negative Attitudes Toward People with Sickle Cell Disease. This article explores the use of the word “sickler” and its association with attitudes and practice patterns of emergency physicians. It demonstrates how using labels for chronic conditions, such as “sickler” for a person with sickle cell disease, can affect the attitude of the healthcare provider.

- Do Words Matter? Stigmatizing Language and the Transmission of Bias in the Medical Record. This article demonstrates how stigmatizing language in the medical record influences the attitudes of physicians-in-training and resulted in less aggressive pain management.

- Should I Say “Disabled People” or “People with Disabilities”? Language Preferences of Disabled People Between Identity- and Person-First Language. This article reports the findings from an international survey describing the identity language preferences of disabled people. Additionally, it investigates the prevalence of identity vs person-first language in the published literature, as well as provides recommendations for researchers on using appropriate language to refer to disabled people. A good article for introducing the topic of identity language and reflect on current and best practices.

- Preferences for Identity-First versus Person-First Language in a US Sample of Autism Stakeholders. The primary goal of the study was to survey autism stakeholders in the United States to determine preferences for identity language. They found that while autistic people preferred IFL, “autism professionals” had a preference for PFL. They highlight the need for professionals to actively engage with individuals to determine identity language preference, and potentially revisit language standards in the academic and professional environment.

- Prevalence of Person-First Language in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. This study examined identity language describing obesity in case report abstracts on IIH. They found that 72% of abstracts used non-PFL language to describe patients who are obese, and posit that a transition to PFL language to describe obesity can decrease stigma on this patient population.

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

- Do you typically use person-first or identity-first language to describe an individual? Does it change in the clinical vs. non-clinical environment?

- How do identity terms have the potential to impact provider bias and patient care? What images come to mind when someone says a patient is an IV drug user vs. a person who uses IV drugs (substitute for alcoholic, diabetic, paraplegic, disabled, obese, etc.)?

- How does language choice influence medical trainees or contribute to the "hidden curriculum"?

- Should medicine default to a specific category or identity language (person-first vs. identity-first)?

- What interventions can be made in our community (or department or residency program) to promote inclusivity through identity language?

Summary/Take-Home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- Language gives the individual an opportunity to reinforce their identity unique from dominant cultural groups, but also has the ability to reinforce stigma, otherness, and negative stereotypes of people that can lead to significant consequences on physical and mental health, create and reinforce disparity, and detract from inclusivity.

- Person-first language puts the person before the disability or condition (i.e. "a person with autism" or "a person who is blind"). Identity-first language emphasizes the marker of identity a particular group chooses to highlight (i.e. "an autistic person" or "a disabled person").

- Ultimately, the method in which a person chooses to self-identify is up to them, and they should have agency to determine their preferred identity language. When in doubt, engage in honest discussion and ask.

Relevant Quotations

Meaningful and relevant quotations (appropriately attributed) can be used to enhance presentations on this topic.

- "Words have power. They reflect attitudes that speakers want to exchange." -Sharif et al. 2022.

- "Identity-first language (IFL), which emphasizes the disability identity of the person, can help reclaim once pejorative terms (such as 'crippled') used for disabled people, and can be instrumental in driving social change. Additionally, IFL can help increase public visibility to the stigma disabled people experience as an underrepresented minority group and assist in reducing that stigma to build a more inclusive society." -Sharif et al. 2022.

- "Reclaiming the word disability...cultivates reappropriate for the disabled community, such that the word disability, at one time pejorative, has been reclaimed by disabled people and reinforced as acceptable language within society." -Best et al. 2022.

- "Clinicians may acquire implicit bias towards patients from one another when communicating verbally or when writing or reading medical records; physicians-in-training may absorb these attitudes as part of the 'hidden curriculum' of medical training." -Goddu et al. 2019.

Specialty Resource Links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

Words Matter: AAP Guidance on Inclusive, Anti-biased Language. American Academy of Pediatrics guide on use of inclusive, anti-biased language

Examination of Stigmatizing Language in the Electronic Health Record. Improved conscientiousness and training around avoiding stigmatizing language in medical notes could improve health equity

Community Resource Links

Below are links to educational resources or supportive programs in the community that are working on this topic.

Advancing Health Equity: Guide to Language, Narrative, and Concepts. AMA and AAMC foundational toolkit to promoting health equity

The Shift to Identity-First Language. This module provides basic background to identity language and best practices

Inclusive Language Guide. A more in-depth and broader discussion of identity language

Person-First and Destigmatizing Language. Guidelines from the NIH on describing specific identities in academic writing

Inclusive Language Guidelines. Comprehensive inclusive language guide for academic writing from the American Psychological Association

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

Person-First or Identity-First Language for Autistic People. Presenter identifies as Autistic.

Conversations with Ivanova: People-First and Identity-First Language. Identity language preference.

Identity or Person-First Language? Lindsey Malc. BCBA - Side by Side Therapy. Breaking down person vs. identity first language

Quiz Questions

- Provide an example of identity- vs. person-first language frequently encountered in medicine.

- Should medical providers utilize identity- or person-first language when addressing patients?

- True or False: preferences for identity language vary across and within identity groups.

Answer Key

- Autistic person vs. person with Autism; substance user vs. person with substance use disorder; trans vs. transgender person; deaf vs. person who is deaf.

- There is no clear consensus, although the APA suggests person-first language. Ultimately, the right answer is the patient's preference, and when in doubt, just ask.

- True.

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in presentation closing.

Patients who identify with non-dominant sociocultural groups report experiencing stigma, discrimination, and “othering” from providers when seeking medical care. These moments can act as a barrier to engaging with the medical system and contribute to health disparities. Appropriate identity language can potentially build rapport and trust with patients through affirming their identity and identity language preferences. Words have incredible power, and physicians must employ them in a culturally competent and reaffirming way to effectively care for the diverse communities in our Emergency Rooms.

References

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

Dunn DS, Andrews EE. Person-First and Identity-First Language: Developing Psychologists’ Cultural Competence Using Disability Language. American Psychologist, 2015;70(3):255-264.

Best KL, Mortenson WB, Lauzière-Fitzgerald Z, Smith EM. Language Matters! The Long-Standing Debate Between Identity-First Language and Person-First Language. Assistive Technology. 2022;34(2):127-128.

Baker EA, Hamilton M, Culpepper D, McCune G, Silone G. The Effect of Person-First Language on Attitudes Toward People with Addiction. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling. 2022;43:38–49.

Taboas A, Doepke K, Zimmerman C. Preferences for Identity-First versus Person-First Language in a US Sample of Autism Stakeholders. Autism. 2023 Feb;27(2):565-570.

Vosoughi A, Pandya B, Mezey N, Tao B, Micieli J. Prevalence of Person-First Language in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology.

Botha M, Hanlon J, Williams GL. Does Language Matter? Identity-First Versus Person-First Language Use in Autism Research: A Response to Vivanti. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023 Feb;53(2):870-878.

Sharif A, McCall A, Bolante, K. Should I Say “Disabled People” or “People with Disabilities”? Language Preferences of Disabled People Between Identity- and Person-First Language. Proceedings of the 24th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility. 2022;1–18.

Bryan K. Eldredge. My Mother Made Me Deaf : Discourse and Identity in a Deaf Community. Gallaudet University Press; 2017.

Glassberg J, Tanabe P, Richardson L, Debaun M. Among Emergency Physicians, Use of the Term “Sickler” is Associated with Negative Attitudes Toward People with Sickle Cell Disease. Am J Hematol. 2013 June;88(6):532-3.

P Goddu A, O'Conor KJ, Lanzkron S, Saheed MO, Saha S, Peek ME, Haywood C Jr, Beach MC. Do Words Matter? Stigmatizing Language and the Transmission of Bias in the Medical Record. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 May;33(5):685-691.

Robling K, Cosby C, Parent G, Swapnil G, Chesher T, Baxter M, Hartwell M. Person-Centered Language and Pediatric ADHD Research: a Cross-Sectional Examination of Stigmatizing Language Within Medical Literature. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2023;123(4):215-222.

Disability. American Psychological Association.

Woodridge S. Writing Respectfully: Person-First and Identity-First Language. National Institutes of Health. 2023 Apr 12.

Person-First and Destigmatizing Language. National Institutes of Health.

Ferrigon P. Person-First Language vs. Identity-First Language: An Examination of the Gains and Drawbacks of Disability Language in Society. Journal of Teaching Disability Studies.