Dealing with Racist or Bigoted Patients and Colleagues

Dealing with Racist or Bigoted Patients & Colleagues

Author: Katrina Gipson, MD, MPH

Editor: Marquita S. Norman, MD, MBA

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

Race: any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry.2 *The American Medical Association recognizes race as a social, not biological construct.3

Racist: having, reflecting, or fostering the belief that race is a fundamental determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race.4

Bigoted: blindly devoted to some creed, opinion, or practice, especially having or showing an attitude of hatred or intolerance toward the members of a particular group (such as a racial or ethnic group).5

Synonyms/Related Terms

This section highlights the definitions of other words that may be used in discussion of this topic. Sometimes these words can be used interchangeably with the terms defined above, and sometimes they may have been used interchangeably historically, but have distinct meanings in DEI conversations that is helpful to recognize.

Prejudice: an unfair feeling of dislike for a person or group because of race, sex, religion, etc.7

Discrimination: the practice of unfairly treating a person or group of people differently from other people or groups of people.8

Microaggressions: a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority).6

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

For a 1-minute presentation: define relevant terms and share take home themes.

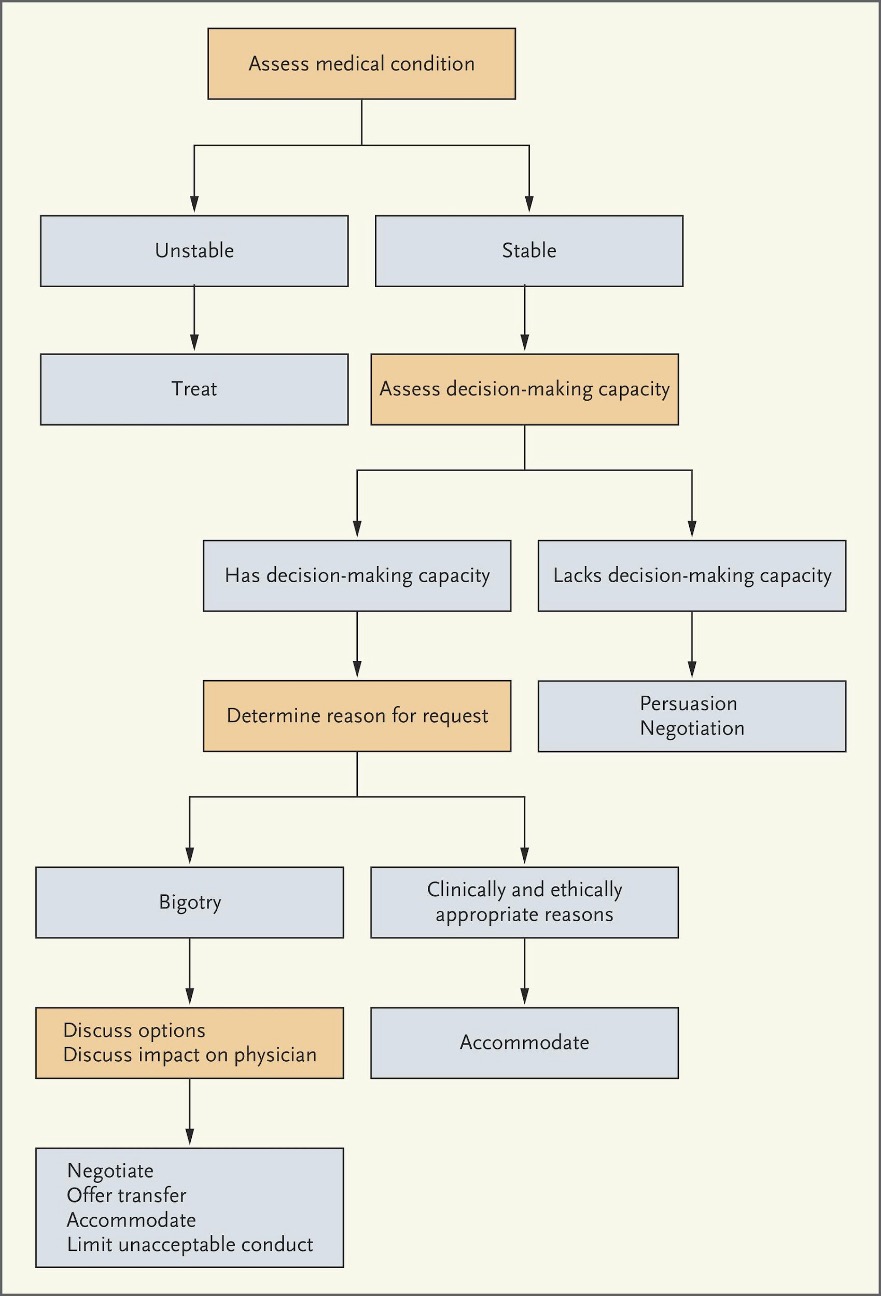

For a 10-minute presentation: define relevant terms, utilize flowchart for considering patient request for patient reassignment, discuss how physicians may intervene when they witness colleagues experience racism, and share take home themes.

For a 30-minute presentation: define relevant terms, review role playing scenario and discussion questions, utilize flowchart for considering patient request for patient reassignment, ask summary quiz questions, and share take home themes.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview of this topic so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

Our professional organizations have begun to recognize racism as a public health crisis.9 For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic further highlights pre-existing healthcare inequities. Also, the increasing visibility of police killings of disproportionately black and brown bodies and identity-based violence over the last several years have all solidified the idea that the field of emergency medicine (EM) must commit to antiracist policies and practices. Part of this commitment to antiracism must explore how we deal with racist or bigoted patients and colleagues. The bigoted patient may pose a special dilemma as physicians take oaths to do what is best for our patients. This is particularly true when our patients are critically ill or lack the capacity to make informed decisions regarding their health care. Furthermore, we can't ignore the fact that our colleagues may be the perpetrators of race-, ethnic-, gender-, or identity-based microaggressions and transgressions. We must commit to creating antiracist work environments, which includes holding our colleagues accountable for their actions, committing to continued education regarding issues of race and implicit bias, and being upstanders when we witness offensive behavior.

Racism and bigotry continue to plague the human condition and these beliefs and practices do not stop at the threshold of healthcare facilities. Encounters with racist patients may cause extreme emotional distress for physicians who are racial/ethnic minorities or underrepresented in medicine (URMs). Physicians belonging to marginalized groups already face additional challenges in the workplace. This is often referred to as the minority tax, including but not limited to lack of mentoring and promotional opportunities and the increased responsibility of uncompensated diversity and inclusion work.10 The addition of encounters with racist patients can be degrading. Physicians, learners, and staff have the right to work in environments free from discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin according to Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Similarly, competent patients have the right to refuse care. These requests are particularly nuanced when patients belonging to racial/ethnic/religious minority groups request a concordant physician due to a history of discrimination, distrust of the medical field, and studies showing that patients treated by physicians who look like them often receive better care/outcomes.11,12 It is important that all physicians are aware of how to recognize and approach the potentially racist patient’s request. This includes empowering minority physicians/learners who will disproportionately bear this burden, being aware of any department or hospital policies on the matter, and developing curriculum that prepares physicians/learners for such encounters.

Racism from patients is difficult, but when it comes from our colleagues, this may be particularly distressing. EM is an extremely collaborative field. This collegial environment may be damaged when we experience or witness racial hostility from our coworkers. This is an extremely widespread issue with some studies reporting that a majority of physicians of color report having experienced racism not only from patients but from their colleagues and institutions as well.13 Racism from colleagues may manifest itself in the form of witnessed implicit biases or microaggressions towards patients. For instance, patients from certain racial/ethnic minority groups may be assumed to be drug seekers, less adherent with their care plans, inherently violent, or have higher pain tolerances by some physicians. Additionally, physicians of color may be less likely to be considered for promotion or leadership and professional development opportunities leading to promotion.10 During patient care, physicians of color may be less likely to be perceived as physicians by other physicians, nurses, or EMS staff. Furthermore, there may be few policies or support networks in place that make physicians of color feel as if they can report incidents of racist or discriminatory behavior free of impunity.

The healthcare field and EM have recently committed to focusing on racism as a public health crisis as well as being antiracist. This commitment necessitates the responsibility of recognizing ways in which racism and bigotry are perpetuated in our field. With that recognition comes the uncomfortable topics of caring for racist patients and dealing with racist colleagues. Caring for racist patients requires that we are quickly able to assess patient capacity, differentiate between reasonable physician-patient concordance requests, and maintain the dignity of our colleagues who are most likely to be the recipients of this racism. Additionally, we must provide continued learning opportunities so that providers can begin to recognize their own implicit biases and ways to address them prior to them negatively affecting patient care. Finally, it is important that our emergency departments, hospitals, and professional organizations have policies and practices in place that define, deter, and correct discriminatory behavior in the workplace.

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of Note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

- Nelson et al used anonymous surveys before and after their training intervention assessing the awareness of racism and its impact on care, with results showing that participants dismantled previously held racist beliefs in all participants.14

- White study participants showed decreased self-efficacy when treating patients of color when compared with White patients.15

- 23% of 71 participants in a mixed-methods, cross-sectional survey design reported that a patient had refused their care due to their race.13

- Qualitative analysis shows that most study participants experienced significant racism from patients, colleagues, and institutions.13

- Educational workshops discussing the intent and impact of microaggressions in healthcare settings and how to respond to them are effective with a 4-point Likert scale, revealing that 98% of participants felt confident identifying microaggressions and 85% felt confident interrupting microaggressions when they occur.16

Slide Presentation or Images

Images and graphical representations can clarify concepts and enhance interest. Please cite the sources of these images appropriately if you use them in your presentation, found below. We purposefully avoided providing complete slide decks in this curriculum, and instead opted to offer easy building blocks for a great personalized presentation regardless of the format.

Considering a patient's request for physician reassignment based on race or ethnic background in an emergency setting.1 Actions in the orange boxes address factors that physicians should consider when confronted with a request to change clinicians because of a clinician's race or ethnic background. Such requests may be deemed to be clinically and ethically appropriate if, for instance, they are motivated by a desire for racial, ethnic, or language concordance or if the patient has specific mental health issues.

Role-Playing Scenarios

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

- A multicultural group of physicians and medical students walk into a white male patient's room for sign-out during shift change. The patient, who has decision-making capacity, loudly proclaims, "I don't want any Black doctors involved in my care! Get [him/her] out of here!"

- You're in the trauma bay on a busy Saturday night. You've just finished caring for a gunshot victim when you overhear one of your colleagues say, "Those people are always shooting each other. He probably deserved it and certainly doesn't need narcotics. He could be a drug addict!"

- The Department Chair comes to the emergency department to introduce everyone to the new hospital CMO. The Chair introduces all the male (or white) physicians as "Dr. [Last Name]" and all the female physicians (or physicians of color) by their first names.

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (i.e. a white facilitator presenting on antiracism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

Dissenting opinions may occur in discussing when it's appropriate or ethical to allow a patient to refuse care from a physician based on the physician's perceived race, ethnicity, or gender, especially in non-emergent settings. You may cite work showing that racial/ethnic minorities who have historically been discriminated against in the healthcare field or women experiencing disease commonly described in men, e.g., heart attacks, often experienced better outcomes when they receive care from concordant physicians:

- Patient-physician gender concordance and increased mortality among female heart attack patients.11

- Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns.11

- The Effects of Race and Racial Concordance on Patient-Physician Communication: A Systematic Review of the Literature.12

Opportunities

Sometimes DEI topics can present depressing history and statistics. This section highlights glimmers of hope for the future: exciting projects, areas of study inspired by the topic, or even ironic twists where progress has emerged or may be anticipated in the future.

While large quantitative analyses regarding experiences with racist patients and colleagues is lacking, small-study qualitative data is promising. The literature strongly supports the idea that curriculum facilitates the identification of implicit biases and positively impacts future patient and intercollegiate interactions.

Journal Club Article Links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

- Managing Patient Bias: Teaching Residents to Navigate Racism and Bias in the Workplace.18 This article explores how the use of modules empowers learners and physicians to respond to patient-initiated race-based discrimination and microaggressions.

- The Time is Now: Racism and the Responsibility of Emergency Medicine to Be Antiracist.19 This article offers a comprehensive social-ecological framework detailing how emergency medicine can be intentionally antiracist ranging from the individual level all the way to community and policy levels.

- Interrupting Microaggressions in health Care Settings: A Guide for Teaching Medical Students.16 This article explores the development of a workshop that helps learners to discuss the intent of microaggressions as well as productive ways to respond to them.

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

- How might physicians intervene on behalf of their colleagues when they witness discriminatory behavior?

- Are we as physicians obligated to oblige patients' requests regarding physician preferences? Does it depend on the patient's mental status or acuity of the illness? Does my institution have a policy on this topic?

- Are you familiar with your hospital/department's policies regarding reporting discriminatory behavior? What are potential barriers to reporting problematic behavior?

Summary/Take-Home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- It is important to delineate between reasonable patient-physician concordance requests from historically marginalized groups and refusal of care steeped in racism while maintaining the dignity of physicians, patients, and an antiracist work environment.

- The field of emergency medicine must commit to being antiracist by promoting ongoing participation by learners, faculty, and staff in dynamic curriculum that defines racism, bigotry, microaggressions, and implicit biases as well as how to confront and decrease these practices at the individual and organizational level.

- Healthcare settings must create clear policies by which faculty and staff must adhere to maintain antiracist work environments as well as ways in which faculty and staff can report misconduct free of fear of punitive backlash.

Specialty Resource Links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

The Time is Now: Racism and the Responsibility of Emergency Medicine to Be Antiracist. This article offers a comprehensive social-ecological framework detailing how emergency medicine can be intentionally antiracist ranging from the individual level all the way to community and policy levels.19

Community Resource Links

Below are links to educational resources or supportive programs in the community that are working on this topic.

- Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, The Ohio State University. Includes several modules defining and exploring implicit bias.20

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

Quiz Questions

- Which statute protects healthcare employees from discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin?

- When might it be appropriate for a patient to request a physician of a certain race/ethnicity/gender?

- Describe the differences between being "antiracist" and "non-racist."

Answer Key

- Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

- Physician-patient concordance requests from marginalized communities

- Antiracism is a positive term that describes people who actively work to understand, explain, and solve racial inequity and injustice. Unlike racist or antiracist, there is no consistent definition for "not racist."24

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in presentation closing.

For individuals belonging to groups less likely to experience racism/bigotry on the job: I will use my position of privilege to intervene on behalf of my colleagues when I witness them experience racism in ways that make them feel supported and empowered while continually working to recognize and minimize my own implicit biases.

For all individuals: I will strive to continually identify my own implicit biases and educational deficits so that we may work in an antiracist environment committed to improving health equity.

References

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

- Paul-Emile K, Smith AK, Lo B, Fernandez, A. Dealing with Racist Patients. N Engl J Med.

- Race. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- New AMA Policies Recognize Race as a Social, Not Biological Construct. American Medical Association. 2016.

- Racist. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- Bigoted. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- Microaggression. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- Prejudice. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- Discrimination. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2019.

- Statement on Structural Racism and Public Health. ACEP. May 30, 2020.

- Campbell KM, Rodriguez JE. Addressing the Minority Tax: Perspectives From Two Diversity Leaders on Building Minority Faculty Success in Academic Medicine. Acad Med. 2019.

- Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-Patient Racial Concordance and Disparities in Birthing Mortality for Newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020.

- Shen MJ, et al. The Effects of Race and Racial Concordance on Patient-Physician Communication: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018.

- Serafini K, Coyer C, Brown Speights J, et al. Racism as Experienced by Physicians of Color in the Health Care Setting. Fam Med. 2020.

- Nelson SC, Prasad S, Hackman HW. Training Providers on Issues of Race and Racism Improve Health Care Equity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015.

- Ricks TN, Abbyad C, Polinard E. Undoing Racism and Mitigating Bias Among Healthcare Professionals: Lessons Learned During a Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021.

- Acholonu RG, Cook TE, Rosell RO, Greene RE. Interrupting Microaggressions in Health Care Settings: A Guide for Teaching Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL. 2020.

- Greenwood BN, Carnahan S, Huang L. Patient-Physician Gender Concordance and Increased Mortality Among Female Heart Attack Patients. Pro Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018.

- Newcomb AB, Rothberg S, Zewdie M, et al. Managing Patient Bias: Teaching Residents to Navigate Racism and Bias in the Workplace. J Surg Educ. 2021.

- Franks NM, Gipson K, Kaltiso SA, Osborne A, Heron SL. The Time is Now: Racism and the Responsibility of Emergency Medicine to be Antiracist. Ann Emerg Med. 2021.

- Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. Implicit Bias Training Modules. OSU. 2017.

- The EveryONE Project. Implicit Bias Resources. AAFP.

- Torjesen I. How do I Deal with a Racist Patient? BMJ. 2023.

- Chary AN, Fofana MO, Kohli HS. Racial Discrimination From Patients: Institutional Strategies to Establish Respectful Emergency Department Environments. West J Emerg Med. 2021.

- Talking About Race. Being Antiracist. National Museum of African American History and Culture.

- Gallo A. Managing Conflicts: How to Respond to an Offensive Comment at Work. Harvard Business Review. 2017.