Ableism

Understanding and Combating Ableism in Medicine: Promoting Access and Inclusion for Individuals with Disabilities Through Systemic Change

Authors: Cori Poffenberger, MD, and Richie Sapp, MD, MS

Definition(s) of Terms

Starting with a common understanding of key words, phrases, and potentially misunderstood related terms in DEI discussions helps ensure that all participants feel informed and welcome to participate in the discussion. Some terms have multiple definitions provided to help highlight nuances in the definitions.

Disability: The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is a law that prevents discrimination against people with disabilities. The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability. The ADA also makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person based on that person's association with a person with a disability.1

Ableism: any statement or behavior directed at a disabled person that denigrates or assumes a lesser status for the person because of their disability. It includes social habits, practices, regulations, laws, and institutions that operate under the assumption that disabled people are inherently less capable overall, less valuable in society, and/or should have less personal autonomy than is ordinarily granted to people of the same age.11 Ableism is a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities and often rests on the assumption that disabled people need to be ‘fixed’ in one form or the other. Ableism is intertwined in our culture, due to many limiting beliefs about what disability does or does not mean, how able-bodied people learn to treat people with disabilities and how we are often not included at the table for key decisions.12 Ableism can take many forms13:

- Lack of compliance with disability rights laws like the ADA

- The use of restraint or seclusion as a means of controlling individuals with disabilities

- Segregating adults and children with disabilities in institutions

- Failing to incorporate accessibility into building design plans

- Buildings without braille on signs, elevator buttons, etc.

- Building inaccessible websites

- The assumption that people with disabilities want or need to be 'fixed'

- Using disability as a punchline, or mocking people with disabilities

- Refusing to provide reasonable accommodations

- The eugenics movement of the early 1900s

- The mass murder of disabled people in Nazi Germany

Minor or every day examples of ableism include13:

- Choosing an inaccessible venue for a meeting or event, therefore excluding some participants

- Using someone else's mobility device as a hand or foot rest

- Framing disability as either tragic or inspirational in news stories, movies, and other popular forms of media

- Casting an actor without a disability to play a disabled character in a play, movie, TV show, or commercial

- Making a movie that doesn't have audio description or closed captioning

- Using the accessible bathroom stall when you are able to use the non-accessible stall without pain or risk of injury

- Wearing scented products in a scent-free environment

- Talking to a person with a disability like they are a child, talking about them instead of directly to them, or speaking for them

- Asking invasive questions about the medical history or personal life of someone with a disability

- Assuming people have to have a visible disability to actually be disabled

- Questioning if someone is 'actually' disabled, or 'how much' they are disabled

- Asking, "how did you become disabled?"

Accessibility: "accessible" means a person with a disability is afforded the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a person without a disability in an equally effective and equally integrated manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use. The person with a disability must be able to obtain the information as fully, equally, and independently as a person without a disability.3

Equity: the quality of being fair, impartial, even, and just.2 To achieve and sustain equity, it needs to be thought of as a structural and systemic concept. Systemic equity is a complex combination of interrelated elements consciously designed to create, support, and sustain social justice. It is a dynamic process that reinforces and replicates equitable ideas, power, resources, strategies, conditions, habits, and outcomes.9

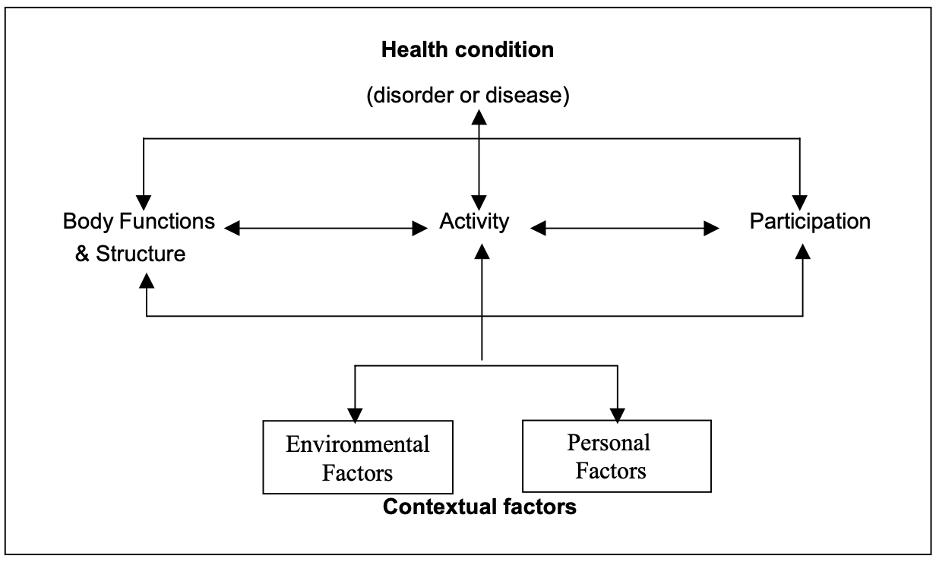

Disability Humility: refers to learning about experiences, cultures, histories, and politics of disability, recognizing that one's own knowledge and understanding of disability will always be partial, and acting and judging in light of that fact.4 Disability is a phenomenon with both medical and social components, and clinicians must work to successfully don what philosopher and bioethicist Erik Parens calls a "binocular" view of disability: a view that thoughtfully fuses both medical and social understandings of disability. Without this binocular vision, clinicians will not have the reflective depth necessary to best diagnose, treat, care for, communicate with, and otherwise interact with patients of abilities of all sorts. Without this binocular vision, clinicians will not achieve optimal health outcomes.4

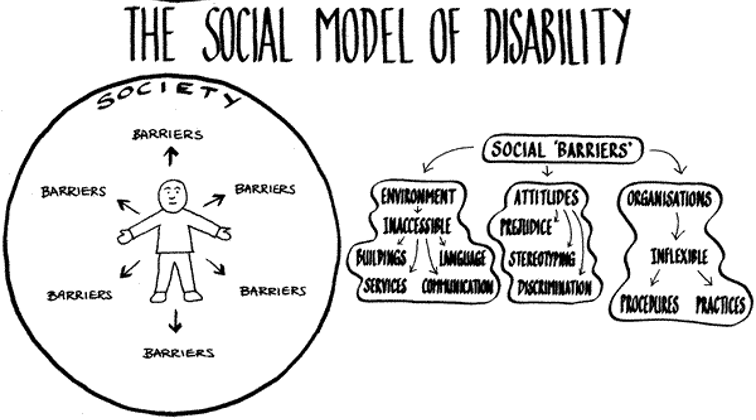

Inclusion: all products, services, and societal opportunities and resources are fully accessible, welcoming, functional, and usable for as many different types of abilities as reasonably possible.2 Disability rights advocates define true inclusion as results-oriented. To this end, communities, businesses, and other groups and organizations are considered inclusive if people with disabilities do not face barriers to participation and have equal access to opportunities and resources. Common barriers to full social and economic inclusion of persons with disabilities include inaccessible physical environments and methods of public transportation, lack of assistive devices and technologies, non-adapted means of communication, gaps in service delivery, discriminatory prejudice and stigma, and systems and policies that are either non-existent or that hinder the involvement of all people in all areas of life. Inclusion advocates argue that one of the key barriers to inclusion is ultimately the medical model of disability, which supposes that a disability inherently reduces the individual's quality of life and aims to use medical intervention to diminish or correct the disability. Interventions focus on physical and/or mental therapies, medications, surgeries, and assistive devices. Inclusion advocates, who generally adhere to the social model of disability, allege that this approach is wrong and that those who have physical, sensory, intellectual, and/or developmental impairments have better outcomes if, instead, it isn't assumed that they have a lower quality of life and they are not looked at as though they need to be "fixed," but rather advocates argue to fix ableist systems, policies, laws, and environments.2

Synonyms/Related Terms

This section highlights the definitions of other words that may be used in discussion of this topic. Sometimes these words can be used interchangeably with the terms defined above, and sometimes they may have been used interchangeably historically, but have distinct meanings in DEI conversations that it is helpful to recognize.

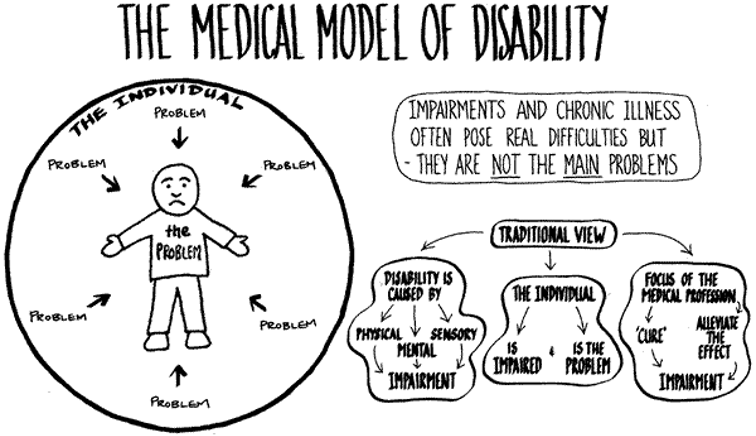

Medical Model of Disability: the medical model views disability as a feature of the person, directly caused by disease, trauma, or other health condition, which requires medical care provided in the form of individual treatment by professionals. Disability, on this model, calls for medical or other treatment or intervention, to 'correct' the problem with the individual.10

Social Model of Disability: the social model sees disability as a socially created problem and not at all an attribute of an individual. On the social model, disability demands a political response, since the problem is created by an unaccommodating physical environment brought about by attitudes and other features of the social environment.10

International Classification of Functioning (ICF): Per the World Health Organization, on their own, neither the social or medical model of disability is adequate, although both are partially valid. Disability is a complex phenomena that is both a problem at the level of a person's body, and a complex and primarily social phenomena. Disability is always an interaction between features of the person and features of the overall context in which the person lives, but some aspects of disability are almost entirely internal to the person, while another aspect is almost entirely external. In other words, both medical and social responses are appropriate to the problems associated with disability; we cannot wholly reject either kind of intervention. A better model of disability, in short, is one that synthesizes what is true in the medical and social models without making the mistake each makes in reducing the whole, complex notion of disability to one of its aspects. This more useful model of disability might be called the biopsychosocial model. ICF is based on this model, an integration of medical and social. ICF provides, by this synthesis, a coherent view of different perspectives of health: biological, individual, and social.10 The following diagram is one representation of the model of disability that is the basis for ICF:

Microaggressions: everyday verbal or behavioral expressions that communicate a negative slight or insult in relation to someone's gender identity, race, sex, disability, etc.13 In the case of ableism:

- "That's so lame"

- "You are so r******* (r-word)"

- "That guy is crazy"

- "You're acting so bipolar today"

- "Are you off your meds"

- "It's like the blind leading the blind"

- "My ideas fell on deaf ears"

- "She's such a psycho"

- "I'm super OCD about how I clean my apartment

- "Can I pray for you?"

- "I don't even think of you as disabled"

Phrases like this imply that a disability makes a person less than, and that disability is bad, negative, and/or a problem to be fixed, rather than a normal, inevitable part of the human experience. Many people don't mean to be insulting, and a lot have good intentions, but even well-meant comments and actions can take a serious toll on their recipients.

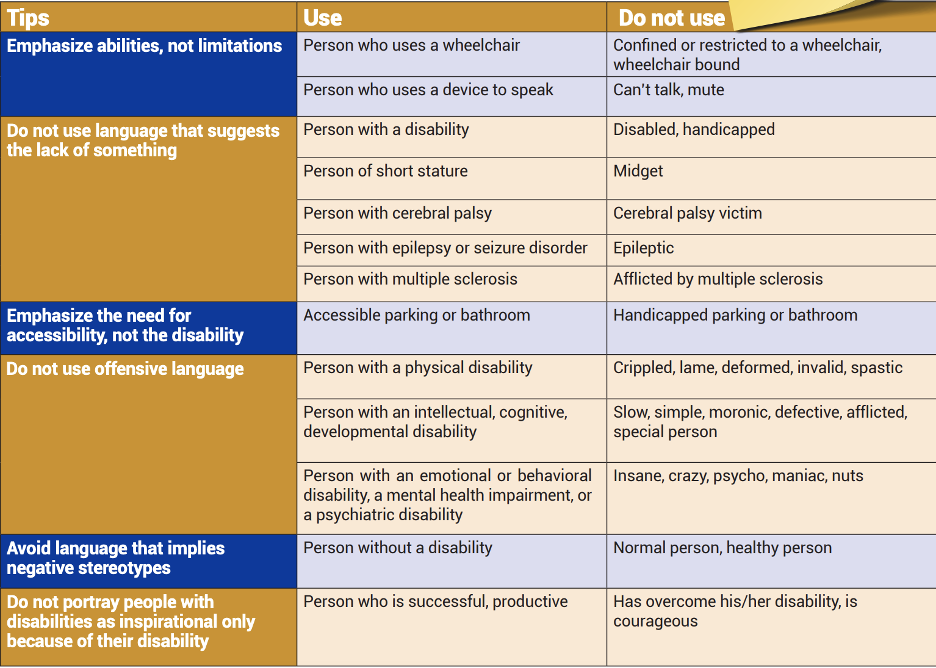

Disability Language: important Do's and Don'ts14-17:

- Recognize obviously insulting terms and stop using or tolerating them.

- Aim to be factual, descriptive, and simple, not condescending, sentimental, or awkward.

- Respect disabled people's actual language preferences.

People-first language is based on the idea that the person is not identified by their disability (i.e. "people who are blind" instead of "blind people"). Identity-first language means that the person feels that the disability is a strong part of who they are and they are proud of their disability (i.e. "disabled person" vs "person who has a disability"). Ultimately, people with disabilities decide how their disability should be stated. Some may choose people-first language while others use identity-first language. At this time, people-first language is recommended for use by anyone who doesn't have a disability and for professionals who are writing or speaking about people with disabilities. Language is dynamic and nuanced, changing at a rapid pace along with social norms, perceptions, and opportunities for inclusion. CDC language guide14:

- People-first language is the best place to start when talking to a person with a disability.

- If you are unsure, ask the person how they would like to be described.

- It is important to remember that preferences can vary.

When writing about disability16:

- Refer to a disability only when it's relevant to the story and, when possible, confirm the diagnosis with a reputable source, such as a medical professional or other licensed professional.

- When possible, ask sources how they would like to be described. If the source is not available or unable to communicate, ask a trusted family member, advocate, medical professional, or relevant organization that represents people with disabilities.

- Avoid made-up words like "diversability" and "handicappable" unless using them in direct quotes or to refer to a movement or organization.

- Be sensitive when using words like "disorder," "impairment," "abnormality," or "special" to describe the nature of a disability. The word "condition" is often a good substitute that avoids judgment, but note that there is no universal agreement on the use of these terms. "Disorder" is ubiquitous when it comes to medical references; and the same is true for "special" when used in "special education," so there may be times when it's appropriate to use them. Proceed with extra caution.

- Similarly, there is not really a good way to describe the nature of a condition. As you'll learn about in other sections, "high functioning" and "low functioning" are considered offensive. "Severe" implies judgment; "significant" might be better. Again, proceed with caution.

Scaling This Resource: Recommended Use

As many users may have varying amounts of time to present this material, the authors have recommended which resources they would use with different timeframes for the presentation.

For a 1-minute presentation: Define ableism and discuss an example of how it manifests in healthcare. Discuss the medical vs social models of disability. Define disability based on the ADA and discuss who might be covered under this law.

For a 10-minute presentation: Define and discuss medical vs social models of disability, the ICF, ableism, and representation of providers with disabilities (you could also touch on technical standards). Discuss the experience of patients with disabilities in healthcare, with examples of healthcare disparities.

For a 30-minute presentation: Define and discuss medical vs social models and ableism. Go over ableism examples and microaggressions in detail, utilizing microaggressions as a leading point for discussion. Utilize the ableist privilege checklist as a pre- or post-session learning tool.

For an hour-long presentation: Discuss definitions, medical vs social models, ableism, and healthcare disparities for 30-40 minutes, followed by small group discussion for the discussion questions. Alternatively, you can use the final 30 minutes for a patient panel with a Q+A session.

Discussion/Background

This section provides an overview of this topic so that an educator who is not deeply familiar with it can understand the basic concepts in enough detail to introduce and facilitate a discussion on the topic. This introduction covers the importance of this topic as well as relevant historical background.

People with disabilities make up a large proportion of our population, but are underrepresented in medicine. This lack of representation is one factor that promulgates an ableist environment in medicine, both for care of patients with disabilities and also for healthcare learners and providers with disabilities. Disability is a frequently overlooked aspect of conversations and strategies aimed at increasing diversity. Healthcare workers with disabilities have a unique perspective, one that provides valuable insight into ways our system promotes marginalization and creates healthcare disparities for those with disabilities. Improving healthcare through systemic change requires listening to and involving individuals with disabilities, both from within healthcare and outside, to promote a more equitable environment, to promote accommodations and universal design, and to dismantle ableism.

Before discussing ableism in medicine, it is important to have a clear background in the definitions and frameworks used regarding disability. Below we will discuss key definitions, legislation, disability etiquette and best practices, and important frameworks that will frame the discussion as it applies to medicine.

Legal Framework

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law in 1990. The ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public. The purpose of the law is to make sure that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else.5 The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability but are regarded as having a disability. The ADA also makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person based on that person's association with a person with a disability.1

Section 504: The ED Section 504 regulation similarly defines an "individual with handicaps" as any person who (i) has a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities, (ii) has a record of such an impairment, or (iii) is regarded as having such an impairment. The regulation further defines a physical or mental impairment as (A) any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological; musculoskeletal; special sense organs; respiratory, including speech organs; cardiovascular; reproductive; digestive; genitourinary; hemic and lymphatic; skin; and endocrine; or (B) any mental or psychological disorder, such as mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities. The definition does not set forth a list of specific diseases and conditions that constitute physical or mental impairments because of the difficulty of ensuring the comprehensiveness of any such list.6

Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA): IDEA (PL 101-476), the law governing rights to special education services, defines disability for the purpose of determining who is eligible for special education services (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities, 2011)7,8:

- Intellectual Disability, hearing impairments (including deafness), speech or language impairments, visual impairments (including blindness), serious emotional disturbance, orthopedic impairments, autism, traumatic brain injury, other health impairments, or specific learning disabilities.

- Who, by reason thereof, needs special education and related services.

Types of Disabilities and Examples

- Mobility: spinal cord injuries, paralysis, amputation

- Psychiatric: depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, post traumatic stress

- Auditory: deaf, hearing impaired

- Cognitive/Developmental/Intellectual: autism spectrum, learning disabilities

- Speech: speech impediment, vocal paralysis

- Environmental: allergies, chemical sensitivities

- Medical: impacts from conditions such as cancer, AIDS, epilepsy, asthma, diabetes, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), cystic fibrosis, severe arthritis

Multiple definitions of disabilities exist with some definitions being more encompassing for human rights legislation and some more restrictive when it comes to accessing services.

Click here for a more in-depth analysis into ableism, including a discussion on the Ableist Privilege Checklist.

Quantitative Analysis/Statistics of Note

This section highlights the objective data available for this topic, which can be helpful to include to balance qualitative or persuasive analysis or to help define a starting point for discussion.

1 in 4 (61 million) US adults report having a disability.18

In 2019, 4.6% of medical students reported disabilities, which is an increase from 2.7%.19

In a study that used a representative sample of 6000 physicians, 178 physicians (3.1%; 95% CI, 2.6-3.5%) self-identified as having a disability.20

In 2012, people with disabilities were about two times as likely to visit the emergency department (ED) compared to people without disabilities.38

People with disabilities accounted for almost 40% of the annual visits made to US EDs each year. Three key factors affect their ED use: access to regular medical care (including prescription medications), disability status, and the complexity of the individuals' health profiles.39

43% of emergency medicine (EM) residency program directors who responded to the survey included disability-specific content in their residency curricula for an average of 1.5 total hours annually, in contrast to average desired hours of 4.16 hours. Reported barriers to disability health education included lack of time and lack of faculty expertise. A minority of residency programs have faculty members (13.5%) or residents (26%) with disclosed disabilities. The prevalence of EM residents with disabilities was 4.02%. Programs with residents with disabilities reported more hours devoted to disability curricula (5 hours vs 1.54 hours, p=0.017).40

The ADA mandates that patients with disabilities receive reasonable accommodations. In Iezzoni et al., survey of 714 US physicians nationwide, 82.4% reported that people with significant disability have worse quality of life than nondisabled people. Only 40.7% of physicians were very confident about their ability to provide the same quality of care to patients with disability, just 56.5% strongly agreed that they welcomed patients with disabilities into their practices, and 18.1% strongly agreed that the health care system often treats these patients unfairly.22

Role-Playing Scenario

Role-playing scenarios can enhance investment and participation. Always consider psychological safety when asking participants to engage in any role-playing activity to avoid potential adverse effects. We highly recommend a discussion for each group to agree on ground rules of respectful learning prior to engaging in any role-playing scenarios (embrace ambiguity, commit to learning together, listen actively, create a brave space, suspend judgment, etc.). It is reasonable to review these ground rules prior to each role-playing discussion.

- Joanna (they/them) is a fourth-year medical student with type I diabetes, who needs frequent opportunities to check and manage their blood sugar. Their Office of Accessible Education accommodations letter specifies that they can take frequent bio breaks without specifying why they need them. Joanna is about to start their ICU rotation. You are the attending on service for Joanna's first week. How would you best provide an inclusive and supportive learning environment for the team? What do you anticipate the barriers or challenges might be?

Barriers/Challenges/Controversies

This section should help the facilitator anticipate any questions, naysayers, rebuttals, or other feedback they may encounter when presenting the topic and allow preparation with thoughtful responses. Facilitators may experience concerns about their personal ability to present a specific DEI topic (i.e. a white facilitator presenting on antiracism or minority tax), and this section may address some of those tensions.

Does including individuals with disabilities as healthcare providers weaken our standards and/or the healthcare team? Aren't people with disabilities less able to do the job? The medicalization of disability in our society, and of course especially amongst those who are responsible for providing medical care for people with disabilities, results in ableism and the idea that people with disabilities are "less than." Combating this idea requires analyzing our understanding of disability and challenging ourselves to incorporate a social model approach. If we design our systems in a way that promotes access and inclusion for all, then people with disabilities are able to do the functions of the job just as well as those without disabilities. This requires flexibility and dismantling our often rigid adherence to doing things the way they have always been done.42

Isn't it good to "fix" differences to help individuals with disabilities function better in the world? The answer to this is situation-dependent. It depends on what the individual wants, and how those "fixes" will improve function. The important thing is that the focus should be on function and on the voiced needs of the individual with disability, rather than on making the individual more like those without disabilities just for the sake of helping them to "fit in."

I find individuals with disabilities in healthcare so inspirational. I am impressed that they are able to be successful given all they suffer. Should I tell them that? Individuals with disabilities should not be called inspirational for doing things that would not be considered inspirational for a non-disabled individual. This is called inspiration porn, a term coined by disability activist Stella Young.43 Inspiration porn takes many forms, but generally relies on the premise that disability is tragic or sad, and that those who are able to live happy/successful/productive/whatever other positive adjective lives are an inspiration rather than the norm. It often centers non-disabled people's perspectives rather than listening to the perspective of people with disabilities. It also can perpetuate the idea that the experience of disability exists solely within the individual rather than resulting from the social organization and structures that exclude people with disabilities.44

Ethical Issues

This section may be useful to hospital ethics committees who want to increase their DEI awareness as part of monthly meetings, or to other groups who are interested in the ethical underpinnings of the topic.

Physicians with Disabilities in Medicine. Physicians with disabilities have often been barred from partaking in medicine due to technical standards in medical school admission processes. When technical standards were created, they focused on a specific set of abilities and attributes that needed to be obtained by graduation to become a doctor in any residency field. Additionally, medical schools and residency programs have been ill-equipped to provide accommodations for individuals with disabilities once they reach that stage in training. Licensure applications ask questions regarding mental health and disabilities. The creation of these processes with the medical model of disability are ableist as they were created without inclusion of individuals with disabilities who may need accommodations, but can perform at the same level as any other individual.

Patient Care. Despite the growing understanding that disability is a normal part of the human experience, the lives of persons with disabilities continue to be devalued in medical decision-making. Negative biases and inaccurate assumptions about the quality of life of a person with a disability are pervasive in US society and can result in the devaluation and disparate treatment of people with disabilities, and in the medical context, these biases can have serious and even deadly consequences. The National Council on Disability has published reports exploring how people with disabilities are impacted by biases and assumptions in some of the most critical healthcare issues we face, including45:

- Organ transplantation

- Physician-assisted suicide

- Genetic testing

- Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)

- Medical futility

Organ Transplant Discrimination. 52% of people with disabilities who requested a referral to a specialist regarding an organ transplant evaluation actually received a referral, while 35% of those "for whom a transplant had been suggested" never even received an evaluation.45

Patients with Disabilities: Avoiding Unconscious Bias When Discussing Goals of Care. False assumptions about patients' quality of life can affect prognosis, the treatment options that we present, and the types of referrals we offer. Complex disability is sometimes equated with terminal illness. This common confusion can result in premature withdrawal of life-preserving care.46

Medical Futility and Disability Bias. Over the past three decades, medical futility decisions by healthcare providers - decisions to withhold or withdraw medical care deemed "futile" or "non-beneficial" - have increasingly become a subject of bioethical debate and face heavy scrutiny from members of the disability community. Health care providers are not exempt from these deficit-based perspectives, and when they influence a critical care decision, the results can be a deadly form of discrimination.45

Examples of Mentorship/Opportunities for UiM Engagement

In recent years, disability has begun to be considered more as an aspect of diversity. Recently, there has been formation of medical student groups highlighting disability such as Medical Students with Disability and Chronic Illnesses33 and groups promoting equity and inclusion amongst residents and faculty including: Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability, Inclusion, and Equity34, MDisability35, the #DocsWithDisabilities podcast36, and the Society for Physicians with Disabilities.37

The percentage of medical students identifying as having disabilities increased from 2.7% in 2016 to 4.6% in 2019.19 Rather than routinely excluding persons with disabilities, more research is needed into including people with disabilities as a unique and important population in healthcare. A recent article reported the number of physicians with disabilities in healthcare as 3.1%.20 A call to action paper in AEM Education and Training highlights the current state of disability education in emergency medicine (EM) residency training, and offers suggestions for improvement, including: designing curriculum using cultural humility, integrating disability into existing curricular and EM milestones, and engaging the disability community outside and within training programs.21

Welcoming disability as an aspect of identity and diversity, and providing accommodations, is beneficial to all health care professionals regardless of ability, as this combats the toxic culture of strength in medicine. This culture is harmful to all who work in the healthcare system. Traditionally healthcare providers have been discouraged from taking care of personal healthcare needs, sacrificing all for the good of their patients or the system in general. Creating a culture that is supportive of accommodations, one where all who work in healthcare are encouraged to address their physical and emotional needs, promotes an equitable and inclusive environment for all that will reduce burnout and promote sustainability.

Through the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine's Academy for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Medicine (ADIEM), there is a group that focuses on disability rights and issues called the Accommodations Committee. Their mission statement is: The ADIEM Accommodations Committee shares the belief that all people have the right to accessible medical care and health care training. It seeks to promote physician delivery of equitable care regardless of a patient’s disability (physical, mental/cognitive, emotional) or cultural/linguistic discordance. The committee also seeks to promote accommodations for health care providers with disabilities.47

Journal Club Article Links

A journal club facilitator can access several salient publications on this topic below. Alternatively, an article can be distributed ahead of a presentation to prompt discussion or to provide a common background of understanding. Descriptions and links to articles are provided.

- Removing Barriers and Facilitating Access: Increasing the Number of Physicians with Disabilities. Commentary article: the authors review the state of disability in medical education and training, summarize key findings from an Association of American Medical Colleges special report on disability, and discuss considerations for medical educators to improve inclusion, including emerging technologies that can enhance access for students with disabilities.48

- Realizing a Diverse and Inclusive Workforce: Equal Access for Residents with Disabilities. The ACGME updated the common core requirements for graduate medical education (GME) programs in 2019 to include a new provision, "The program, in partnership with its Sponsoring Institution, must engage in practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents." To meet this common core requirement, GME programs must create inclusive policies and practices, understand their responsibilities under federal law, and educate themselves regarding reasonable accommodations for learners with disabilities. This article reviews the systemic barriers in GME for residents with disabilities and discusses mechanisms to reframe those barriers as opportunities to build programs that are more inclusive. It is a good starting point for GME programs that seek to include disability as an aspect of diversity in their program.49

- Accessibility, Inclusion, and Action in Medical Education. This report by the AAMC captures the day-to-day experiences of learners and academic medicine physicians with disabilities. By bringing these important voices into the discussion and sharing their lived experiences, this report elucidates the challenges and complexities encountered by these members of the academic medicine community.50

- Emergency Medicine Resident Education on Caring for Patients with Disabilities: A Call to Action. This paper reviews the current state of health care for patients with disabilities and the current state of undergraduate and graduate medical education on the care of patients with disabilities, then provides suggestions for an improved EM residency curriculum that includes education on the care for patients with disabilities.21

- The Prevalence of Disability Health Training and Residents with Disabilities in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. Survey study of EM program directors looking at the current state of disability health education in EM residency programs, as well as the prevalence of residents and faculty with disabilities. Also looks at the association of residents or faculty with disabilities with likelihood of providing education on disability in residency. Good article to start discussion regarding practices for recruitment and retention, as well as review of the curricula regarding diversity topics.40

Discussion Questions

The questions below could start a meaningful discussion in a group of EM physicians on this topic. Consider brainstorming follow-up questions as well.

- What are the barriers for individuals with disabilities to becoming physicians or other healthcare providers?

- How can programs better promote disability as diversity?

- What are examples of ableism within the healthcare system for healthcare providers? For patients? How would you be able to mitigate and improve these institutional problems?

Summary/Take-Home Themes

The authors summarize their key points for this topic below. This could be useful to create a presentation closing.

- Disability is a frequently overlooked aspect of programs that seek to increase diversity. As with other marginalized identities, the belonging of people with disabilities within healthcare makes our teams stronger. Healthcare providers with disabilities have a unique perspective that provides valuable insight into the ways in which our system promotes marginalization and healthcare disparities for disabled patients.

- Like forms of oppression, ableism is codified in the systems and structures that have been put into place in our society. In order to combat ableism, we need to look at the policies and procedures we have put in place that limit the participation of people with disabilities in healthcare.

- Disability is itself diverse, encompassing a variety of differences or impairments. There is no one size fits all to access. The key is to listen to disabled people and to promote universal design as a way to improve the system for all.

Specialty Resource Links

Below are links to Emergency Medicine-specific resources for this topic.

- Emergency Medicine Resident Education on Caring for Patients with Disabilities: A Call to Action. This paper reviews the current state of health care for patients with disabilities and the current state of undergraduate and graduate medical education on the care of patients with disabilities, then provides suggestions for an improved EM residency curriculum that includes education on the care for patients with disabilities.21

- The Prevalence of Disability Health Training and Residents with Disabilities in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. Survey study of EM program directors looking at the current state of disability health education in EM residency programs, as well as the prevalence of residents and faculty with disabilities. Also looks at the association of residents or faculty with disabilities with likelihood of providing education on disability in residency. Good article to start discussion regarding practices for recruitment and retention, as well as review of the curricula regarding diversity topics.40

Video Links

Below are links to videos that do an excellent job of explaining or discussing this topic. Short clips could be used during a presentation to spark discussion, or links can be assigned as pre-work or sent out for further reflection after a presentation.

Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (Netflix documentary).51

Doctors with Disabilities: Perseverance in Practice (YouTube video).52

Disability Does Not Equal Inability (YouTube video).53

Quiz Questions/Answers

Possible questions and an answer key are provided below. These can be useful to document effectiveness in learning and knowledge gained but can also be useful to help learners identify that they may not actually know everything about a DEI topic, even if they have participated in presentations on it previously.

- In the US, what is the percentage of people with disabilities?

- 10-15% of the population

- 20-25% of the population

- 30-40% of the population

- 50-60% of the population

- How does the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) define a person with a disability?

- A person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.

- A person who is unable to do any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment.

- A person, due to illness or injury, either physical or mental, prevents them from performing their regular and customary work.

- A person with any condition of the body or mind (parent impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).

- Regarding accommodations, which of the following is not true?

- When judging students' competency, we should concentrate on the "what" and not the "how." In other words, allowing students to satisfy objectives in a variety of ways, depending on their disability.

- In the clinical setting, accommodations may include bio breaks, schedule modifications, and time off for appointments.

- Accommodations are rights under the law, not special privileges.

- If they are given to one person on a team, they must be given to everyone, regardless of disability status, in order to satisfy human resources equitable treatment mandates.

- Regarding students with disabilities, which of the following is true (select all that apply)?

- We should screen them out in the admissions process in order to avoid future conflict over clinical accommodations.

- They often work harder than their peers to manage the dual responsibilities of their health and education.

- They need accommodations to have equal access to programs, but do not want a less rigorous educational experience.

- Their dual role as patients and future providers is a conflict of interest that must be disclosed.

- Which of the following is the correct way to refer to a learner with a disability?

- Person-first language (person with a disability)

- Identity-first language (disabled person)

- Depends on the individual

- Which of the following is the appropriate term when referring to someone in a wheelchair?

- A person who uses a wheelchair

- A wheelchair-bound person

- A handicapped person

- A person confined to a wheelchair

Answer Key

- 20-25%. While 20-25% of the US population has a condition that could qualify as a disability, only around 5% of medical students and 3% of practicing physicians disclose a disability. These numbers are likely underreported due to stigma around disclosure and barriers to entry into the medical profession.

- "A person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities." ADA is a piece of human rights legislation that has a broad definition of disability and prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities. "Learning" is considered a major life activity. Option 2 is the Social Security Disability Insurance definition. Option 3 is the paraphrased definition of the California Employment Development Department for disability insurance benefits. Option 4 is the paraphrased medical definition defined by the CDC.

- "If they are given to one person on a team, they must be given to everyone, regardless of disability status, in order to satisfy human resources equitable treatment mandates." Providing accommodations is about providing equity to individuals with disabilities, as the way society is structured is the root cause of disability. Equity recognizes that people with disabilities need support to perform the essential duties of their jobs, and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed for each individual. Accommodations are not special privileges, but rather the legal right of people with disabilities.

- Options 1 and 2. Depending on the effort required to manage a disability and chronic illness, it can be like having a second job. Option 1 is illegal and 4 is incorrect. Having the dual role gives one important insight into the minds of both physicians and patients, it is not a conflict of interest.

- "Depends on the individual." Individuals vary on whether they like to be referred as a "person with a disability" or a "disabled person." Person-first language highlights that disability is only one aspect of their identity, while identity-first language highlights that their disability is inherent to their identity and not just something they have.

- "A person who uses a wheelchair." A person who uses a wheelchair is not bound to it nor confined to it. A wheelchair is an assistive device. The term "handicapped" is no longer considered appropriate. A "person with a disability" or "disabled person" are the appropriate terms.

Call to Action Prompt

Below is a statement that inspires participants to commit to meaningful action related to this topic in their own lives. This could be used to prompt reflection, discussion, or could be used in a presentation closing.

Disability is a frequently overlooked aspect of programs that seek to increase diversity. Like other forms of oppression, ableism is codified in the systems and structures that have been put into place in our society. In order to combat ableism, we need to look at the policies and procedures we have put in place that limit the participation of people with disabilities in healthcare as both patients and providers.

References

All references mentioned in the above sections are cited sequentially here.

- What is the definition of disability under the Ada? ADA National Network. (2022, March 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://adata.org/faq/what-definition-disability-under-ada

- Ableism. NCCJ. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.nccj.org/ableism

- Understanding accessibility. Accessibility. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://accessibility.iu.edu/understanding-accessibility/index.html

- Reynolds J. M. (2018). Three Things Clinicians Should Know About Disability. AMA journal of ethics, 20(12), E1181–E1187. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2018.1181

- An overview of the Americans with disabilities act. ADA National Network. (2022, March 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://adata.org/factsheet/ADA-overview

- US Department of Education (ED). (2020, January 10). The civil rights of students with Hidden Disabilities and Section 504. Home. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq5269.html#:~:text=DISABILITIES%20COVERED%20UNDER%20SECTION%20504,as%20having%20such%20an%20impairment

- Sec. 300.8 child with a disability. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2018, May 25). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8

- About idea. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2022, February 15). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/about-idea/

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020, August 25). Equity vs. equality and other racial justice definitions. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.aecf.org/blog/racial-justice-definitions

- ICF beginners guide - who | world health organization. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). Words matter, and it's time to explore the meaning of "ableism.". Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2020/10/25/words-matter-and-its-time-to-explore-the-meaning-of-ableism/?sh=1484b878716

- Smith, L. (n.d.). Center for Disability Rights. #Ableism – Center for Disability Rights. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://cdrnys.org/blog/uncategorized/ableism/

- Ableism 101 - what is ableism? what does it look like? Access Living. (2021, January 8). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 1). Communicating with and about people with disabilities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/materials/factsheets/fs-communicating-with-people.html

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). Here are some DOS and don'ts of disability language. Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2020/09/30/here-are-some-dos-and-donts-of-disability-language/?sh=9610b77d1700

- National Center on Disability and journalism. NCDJ. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://ncdj.org/style-guide/

- Disability language guide - disability.stanford.edu. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://disability.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj1401/f/disability-language-guide-stanford.pdf

- Okoro, C. A. (2018). Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care Access by Disability Status and Type Among Adults—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3

- Meeks, L. M., Case, B., Herzer, K., Plegue, M., & Swenor, B. K. (2019). Change in Prevalence of Disabilities and Accommodation Practices Among US Medical Schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA, 322(20), 2022–2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.15372

- Nouri, Z., Dill, M. J., Conrad, S. S., Moreland, C. J., & Meeks, L. M. (2021). Estimated Prevalence of US Physicians With Disabilities. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e211254. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1254

- Rotoli, J., Backster, A., Sapp, R. W., Austin, Z. A., Francois, C., Gurditta, K., Mirus, C., 4th, & McClure Poffenberger, C. (2020). Emergency Medicine Resident Education on Caring for Patients With Disabilities: A Call to Action. AEM education and training, 4(4), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10453

- Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Donelan, K., Lagu, T., & Campbell, E. G. (2021). Physicians' Perceptions Of People With Disability And Their Health Care. Health affairs (Project Hope), 40(2), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

- Projectimplicit. Take a Test. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html

- Borowsky H, Morinis L, Garg M. Disability and Ableism in Medicine: A Curriculum for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17(1):11073. https://doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11073

- DeLisa, J. A., & Lindenthal, J. J. (2016). Learning from Physicians with Disabilities and Their Patients. AMA journal of ethics, 18(10), 1003–1009. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.10.stas1-1610

- Curry, R. H., Meeks, L. M., & Iezzoni, L. I. (2020). Beyond Technical Standards: A Competency-Based Framework for Access and Inclusion in Medical Education. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 95(12S Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments), S109–S112. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003686

- Kezar, L. B., Kirschner, K. L., Clinchot, D. M., Laird-Metke, E., Zazove, P., & Curry, R. H. (2019). Leading Practices and Future Directions for Technical Standards in Medical Education. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 94(4), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002517

- Lawson N. D. (2020). Eliminate Mental Health Questions on Applications for Medical Licensure. The American journal of medicine, 133(10), 1118–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.04.011

- Rush Medical College Admissions. Admission Requirements - Doctor of Medicine (MD) Program | Rush University. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.rushu.rush.edu/rush-medical-college/doctor-medicine-md-program/admission-requirements

- Blauwet, C. A. (2017, December 6). I use a wheelchair. and yes, I'm your doctor. The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/06/opinion/doctor-wheelchair-disability.html

- Stanford Medicine. (n.d.). A call for more doctors with disabilities. Stanford Medicine. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://stanmed.stanford.edu/listening/time-that-doctor-with-disability-seen-ordinary.html

- BBC. (2021, April 18). The disabled doctors not believed by their colleagues. BBC News. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.bbc.com/news/disability-56244376

- Get involved! MSDCI. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://msdci.org/join-our-movement/

- Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity. (n.d.). Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity (Stanford Med Adie). Stanford Medicine Alliance for Disability Inclusion and Equity. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://med.stanford.edu/smadie.html

- MDisability: Family medicine: Michigan medicine. Family Medicine. (2021, April 29). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability

- Docs with disabilities podcast: Family medicine: Michigan medicine. Family Medicine. (2022, March 8). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/family-medicine/programs/mdisability/transforming-medical-education/docs-disabilities-podcast

- Society for physicians with disabilities. Society for Physicians with Disabilities. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.physicianswithdisabilities.org/

- Kim, A. M., Lee, J. Y., & Kim, J. (2018). Emergency department utilization among people with disabilities in Korea. Disability and health journal, 11(4), 598–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.03.001

- Rasch, E. K., Gulley, S. P., & Chan, L. (2013). Use of emergency departments among working age adults with disabilities: a problem of access and service needs. Health services research, 48(4), 1334–1358. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12025

- Sapp, R. W., Sebok-Syer, S. S., Gisondi, M. A., Rotoli, J. M., Backster, A., & McClure Poffenberger, C. (2020). The Prevalence of Disability Health Training and Residents With Disabilities in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs. AEM education and training, 5(2), e10511. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10511

- Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., Ressalam, J., Bolcic-Jankovic, D., Agaronnik, N. D., Lagu, T., Pendo, E., & Campbell, E. G. (2022). US Physicians' Knowledge About The Americans With Disabilities Act And Accommodation Of Patients With Disability. Health affairs (Project Hope), 41(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01136

- Lu, W. (2021, August 26). Disabled doctors were called too 'weak' to be in medicine. it's hurting the entire system. HuffPost. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/disabled-doctors-medicine-ableism_n_60f86967e4b0ca689fa560dc

- Young, S. (n.d.). I'm not your inspiration, thank you very much. Stella Young: I'm not your inspiration, thank you very much | TED Talk. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much?language=en

- Pulrang, A. (2021, December 10). How to avoid "inspiration porn". Forbes. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewpulrang/2019/11/29/how-to-avoid-inspiration-porn/?sh=4e8cabbe5b3d

- Bioethics and disability report series. NCD.gov. (2022, January 18). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://ncd.gov/publications/2019/bioethics-report-series

- Kripke C. Patients with Disabilities: Avoiding Unconscious Bias When Discussing Goals of Care. American Family Physician. 2017;96(3):192-195. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2017/0801/p192.html

- Accommodations. Default. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies/adiemnew/about/adiem-committees/accommodations

- Meeks, L. M., Herzer, K., & Jain, N. R. (2018). Removing Barriers and Facilitating Access: Increasing the Number of Physicians With Disabilities. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(4), 540–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002112

- Meeks, L. M., Jain, N. R., Moreland, C., Taylor, N., Brookman, J. C., & Fitzsimons, M. (2019). Realizing a Diverse and Inclusive Workforce: Equal Access for Residents With Disabilities. Journal of graduate medical education, 11(5), 498–503. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00286.1

- UCSF Disability Special Report Accessible. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://sds.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra2986/f/aamc-ucsf-disability-special-report-accessible.pdf

- Watch Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution | Netflix Official Site. www.netflix.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.netflix.com/title/81001496#:~:text=Watch%20Crip%20Camp%3A%20A%20Disability%20Revolution%20%7C%20Netflix%20Official%20Site

- Doctors With Disabilities: Perseverance in Practice. www.youtube.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X71TP7hitlo

- Disability Does Not Equal Inability. www.youtube.com. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r81WpiPUMYs