Introduction

Intussusception is a common cause of bowel obstruction in infants and young children. 80-90% of children are less than 2 years of age with a slight male predominance. Intussusception occurs when a portion of the intestine invaginates into itself. The proximal bowel segment (intussusceptum) telescopes into a distal bowel segment (intussuscipiens), pulling the connected mesentery with it. This results in venous insufficiency and bowel wall edema. Necrosis and perforation of the bowel with peritonitis will ensue if left untreated. Unrecognized intussusception can be fatal.

Ileocolic intussusception near the ileocecal junction is most common, but can also be ileo-ileo-colic, jejuno-jejunal, jejuno-ileal or colo-colic. The majority of cases are idiopathic without a known trigger or pathological lead point. Viral infections may be associated with intussusception. The incidence of intussusception increases during times of increased incidence of viral gastroenteritis. A third of patients will have viral symptoms prior to an episode of intussusception. Intestinal lymphatic tissue is stimulated during viral illnesses and may act as a lead point, as can Meckel diverticula, tumors, polyps, duplication cysts, vasculitis or vascular malformations. A lead point is more likely to be found in children older than 2 years.

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the student will be able to:

- List the signs and symptoms of intussusception

- Understand the pathophysiology associated with untreated intussusception

- Describe the evaluation and emergent management of intussusception

- Discuss management options for intussusception

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Assess and address the ABC’s. Evaluate for signs and symptoms of shock. Children in shock are tachycardiac initially. Hypotension is a late and ominous sign in children. Intravenous access should be obtained followed by administration of appropriate fluid to resuscitate based on the clinical status of the patient. Patients with suspected intussusception need to be kept NPO.

Presentation

The classic presentation is the sudden onset of colicky, intermittent abdominal pain. The pain can be episodic with the child appearing well between episodes. Bloody stools and vomiting may also be seen. Some patients will present with lethargy, listlessness or appear to be comatose and can be misdiagnosed as sepsis, being encephalopathic or possibly postictal. An ill-defined “sausage-shaped” mass can occasionally be palpated. The classic triad of abdominal pain, sausage-shaped mass and currant jelly stools (blood and mucous mixed with stool) is seen in 15%-20% of cases. Absence of blood in the stools does not rule out the diagnosis of intussusception.

Diagnostic Testing

Preliminary diagnostic studies can include plain radiographic films of the abdomen. Findings include:

- Normal gas pattern

- Intestinal obstruction with distended bowel and air-fluid levels

- “Target” sign over the right kidney consisting of two concentric radiolucent circles

- “Crescent” sign with a soft tissue density protruding into the gas-filled lumen of the large bowel

- Paucity of air in the cecum

- Signs of perforation with pneumoperitoneum (rare)

KUB: dilated loops of bowel with paucity of gas in cecum

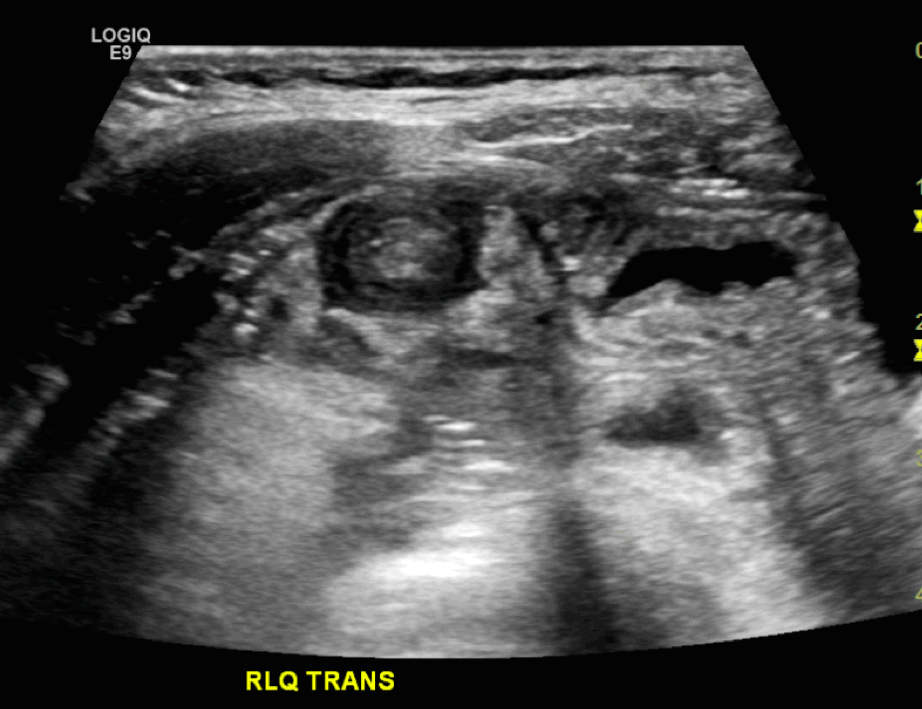

Ultrasonography is the preferred diagnostic study by many. Sensitivity and specificity is near 100% when performed by an experienced ultrasonographer. A “bull’s eye”, “coiled spring” or “target sign” is the classic ultrasound finding. Ultrasound can also identify a lead point in the many of cases of intussusception associated with underlying pathology. Color duplex imaging can demonstrate lack of perfusion and ischemia

Ultrasound demonstrating the “target” “bull’s eye” or “coiled spring” sign

Intussusception can be seen on computed tomography (CT) but is not a preferred modality. CT is used when other radiographic studies are indeterminate or to better identify a pathological lead point.

Treatment

Patients with evidence of bowel perforation require operative intervention. Patients without evidence of bowel perforation are managed by nonoperative reduction using either hydrostatic (barium, water-soluble contrast or saline) or pneumatic pressure enema with either fluoroscopic or sonographic guidance. Reduction is successful in 80-95% with ileocolic intussusception with a risk of perforation is <1% for both hydrostatic and pneumatic pressure enemas. The choice of nonoperative intervention is dependent on the radiologist and institution

Patients require the following prior to enema reduction:

- Stabilization and adequately fluid resuscitation

- Decompression of the stomach with placement of a nasogastric tube

- Surgical consultation

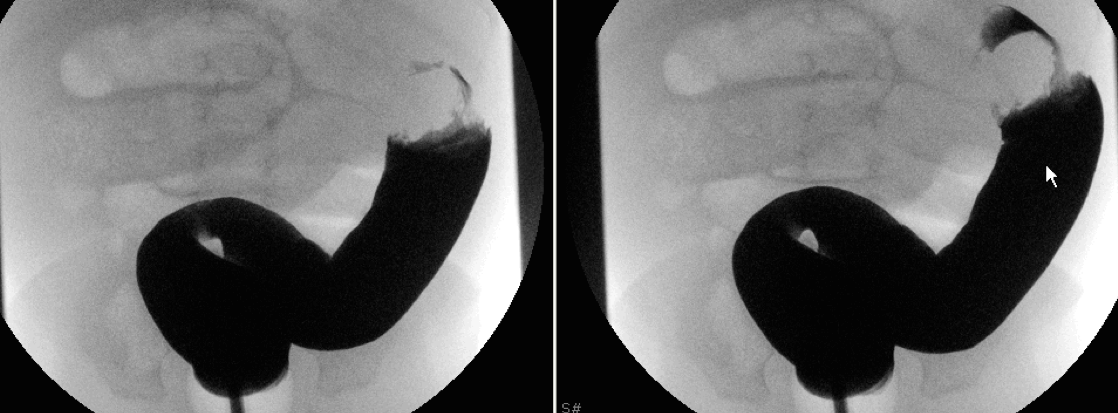

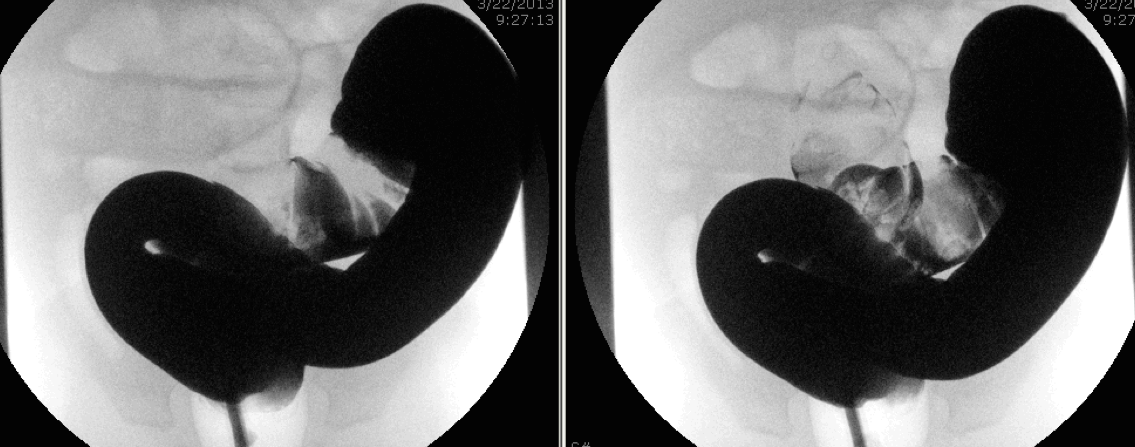

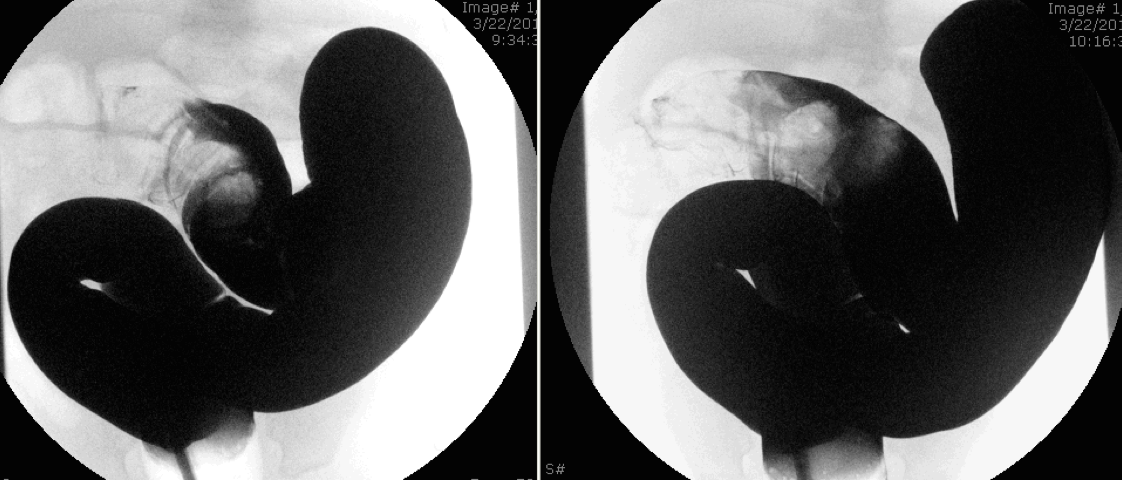

A: Rectal tube with instillation of barium

B Filling defect

C Barium with meniscus sign

D Barium “coiled spring” sign

E Further reduction of the intussusceptum

F Barium enema reduction of intussusception

Patients are usually observed for 12-24 hours after successful nonoperative reduction. Recurrence of intussusception is approximately 10% after nonoperative reduction.

Pears and Pitfalls

- Intussusception is one of the most common causes of obstruction in children 6 months and 3 years of age

- Most children with intussusception are under 2 years of age

- Intussusception usually presents with sudden onset episodic abdominal pain

- Bloody stools and vomiting may also be present

- Children may also present with altered mental status and be misdiagnosed as sepsis, being encephalopathic or postictal

- Ultrasonography is the method of choice to diagnosis intussusception

- Patient require stabilization, adequate fluid resuscitation and placement of nasogastric tube prior to attempted reduction

- Nonoperative reduction is done by either by hydrostatic or pneumatic pressure enema with either fluoroscopic or sonographic guidance

- Surgical evaluation should be done prior to nonoperative reduction in order to prepare in cases of unsuccessful reduction or perforation during enema reduction

References

- Fallon et al. Risk factors for surgery in pediatric intussusception in the era of pneumatic reduction. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23701778

- Freedman et al. Pediatric abdominal radiograph use, constipation and significant misdiagnoses. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24128647

- Gary et al. Recurrence Rates After Intussusception Enema Reduction: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics.2014;133(7):110-119. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25274835

- Jiang et al. Childhood intussusception: a literature review. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23894308

- Lochhead et al. Intussusception in children presenting to the emergency department. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24137037

- Mandeville et al. Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22929138

- Territo et al. Clinical sign and symptoms associated with intussusception in young children undergoing ultrasound in the emergency room. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25272074