Dermatology

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Outline the general approach to describing rashes.

- Describe the basic method on primary assessment of a patient.

- Identify distinguishing features of common pediatric infectious rashes.

- Distinguish life-threatening rashes in children.

Contributors

Update Authors: Alejandro Pasaret, MD; and S. Margaret Paik, MD.

Original Authors: Natalie Yapo, MD; and S. Margaret Paik, MD.

Update Editors: Niresh Perera, MD; and Manpreet Singh, MD, MBE.

Original Editor: Matthew Tews, MD.

Last Updated: July 2024

Introduction

Rash is a common chief complaint for children in the emergency department (ED). The general approach to the evaluation of rashes is to first identify whether the child is sick versus not sick. By going through the ABC’s as well as understanding age-appropriate vital signs, the clinician should be able to identify children that are ill and may require a workup or a timely intervention.

In the initial evaluation, the child’s airway should be assessed. Urticaria may be associated with airway compromise such as stridor or wheezing in the case of anaphylaxis. The child’s breathing should be assessed including the oxygen saturation and respiratory effort. When assessing the child’s circulation, the clinician needs to be aware of whether the heart rate and blood pressure are age-appropriate. The quality of central pulses (brachial, femoral, carotid) is also paramount in the circulation assessment.

When assessing the rash, describing the appearance, distribution and associated symptoms are paramount in figuring out the etiology of the rash.

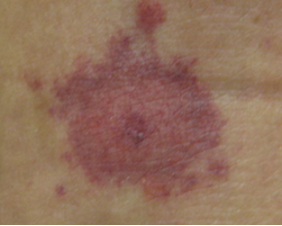

A three-year-old male with no significant PMH presents to the ED with a worsening rash throughout the body. The patient was seen at an outside hospital ED two days ago for mild swelling around the eye and a rash over his body with fevers. Patient was diagnosed with a hordeolum (eye stye), viral exanthem vs eczema, and sent home with topical steroid cream and antibiotic ointment for the eye. Today, the mother states the patient feels unwell and the rash has spread all over their body, with some cracked lips and crusting around the nose. Mother states the whole body is “flushed” and the patient has not been drinking or urinating as much. You enter the patient's room and this is what you see.

Figures: Patient's rash. Images from Dermnet. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

All clinical encounters start with a primary assessment of the patient, which can be done as you are introducing yourself to the patient or family, or even as the patient is being walked or taken into an examination room. A frequently utilized tool for primary assessment in children is the Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT) and the AVPU scale for mental status assessment.

PAT

- Appearance: Tone, interactiveness, consolability, look/gaze, speech/cry.

- Work of Breathing: Abnormal breath sounds, abnormal position, head bobbing, retractions, gasping, nasal flaring.

- Circulation to Skin: Pallor, mottling, cyanosis, absent or weak pulses, abnormal blood pressure, obvious signs of bleeding.

AVPU Scale

- Alert: Not necessarily orientated to time and place or neurologically normal.

- Verbal: Not fully awake, only responds to verbal stimuli.

- Pain: Difficult to rouse and only responds to painful stimuli.

- Unresponsive: Completely unconscious with no response.

Meningococcemia

Meningococcemia, which is due to Neisseria meningitidis, will often present in an ill-appearing patient. Children less than 12 months old are at the highest risk of meningococcemia. Apart from fever, irritability, and meningeal signs and symptoms, two-thirds of those affected will have a cutaneous manifestation. Early on, the rash may appear as morbilliform or urticarial macules and papules that often progress to petechial, pustules, and vesicles. Late cutaneous features will include purpuric (non-blanching) lesions with jagged edges. Confirmatory tests include culture of the blood and CSF.

Figure: Purpuric rash. Image courtesy of Baby Charlotte. Permission to use stored at Wikipedia.

Figure: Purpuric rash on calves. Image courtesy of MedlinePlus, National Library of Medicine. Image not copyrighted.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS)

SSSS is a toxin-mediated rash produced by Staphylococcus aureus. Children less than five years old are usually affected and present with a generalized tender erythroderma and flaccid bullae. SSSS is typically associated with a positive Nikolsky's sign, rubbing of the skin that causes skin desquamation or creates bullae within minutes. The mucous membranes are often spared. Diagnosis is largely a clinical diagnosis as the bullae are sterile.

Figure: Sloughing of the skin around the mouth. Image courtesy of Dermnet. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Figure: Desquamation. Image courtesy of Dermnet. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Figure: Intact and open lesions. Image courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

Figure: Erythroderma with open bullae. Image courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

Herpes Simplex Infection

Herpes Simplex Viral (HSV) infection can cause localized or widespread infection. The classic rash associated with HSV is a painful vesicular (1-2mm) and/or ulcerative rash on an erythematous base. HSV-1 infection typically causes a localized infection of the mouth (herpetic gingivostomatitis), lips, and/or eyes. HSV-2 infection is commonly associated with genital infections and is typically transmitted through sexual contact.

A child with herpetic gingivostomatitis usually has a fever accompanied by a vesicular and/or ulcerative rash of the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingivae, and perioral skin. This differs from herpangina, which commonly appears on the soft palate, tonsillar pillars, uvula, and posterior pharynx (see below for description).

If an HSV rash is located on the digits, it is referred to as a herpetic whitlow. In a child with atopic dermatitis with an overlying herpetic rash, it is referred to as eczema herpeticum.

Usually, treatment options with acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir are most efficacious when given within 48 hours of symptoms. Those with lesions on the eyes should be urgently evaluated by ophthalmology. Those that appear ill, are under six weeks old, show signs of central disease (seizures, lethargy, altered mental status), are immunocompromised, or have widespread eczema herpeticum should be admitted for parenteral therapy.

Figure: Note ulcers below two bottom teeth. Image courtesy of Dr. James Hellman. Used under the CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure: Herpetic lesions on gingiva. Image courtesy of Jeffrey Dorfman. Used under the CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure: Note the vesicular lesions accompanied with conjunctival injection. Image courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

Figure: Note the eczema of arms and face with small ulcerative rash on an erythematous base around the mouth. Image courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

SJS and TEN are characterized by cutaneous and mucous membrane epidermal disruption. IN SJS, the rash is preceded by prodromal symptoms of fever, malaise, headache, and sore throat for 1-14 days. The rash is described as target lesions which are erythematous concentric lesions with central duskiness that may turn into a blister and/or erosion. The rash commonly involves the palms and soles, and <10% of the body surface area is involved in SJS. The hallmark of SJS is the association of a characteristic rash with the involvement of more than two mucosal sites (i.e. oral, conjunctiva, urethral, esophageal). Universally, hemorrhagic crusting of the lips and oral cavity are seen with SJS. The etiology of SJS may be drug-related (i.e. anti-epileptics, NSAIDS, sulfonamides, acetaminophen) or infectious (i.e. HSV, mycoplasma, EBV). Treatment is largely supportive care and discontinuing offending drug agents.

TEN is a severe form of SJS in that >30% of the body surface area is involved. TEN is associated with multi-organ failure, more than two mucosal site involvement, and the rash is characterized by widespread bullae eruption leading to epidermal sloughing. Usually, those with TEN will need to be transferred to a burn unit and receive intensive care monitoring.

Figure: SJS target lesion, note central duskiness. Image courtesy of Kilbad. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Figure: Mucosal desquamation in a patient with SJS. Image courtesy of Dr. James Heilman. Used under the CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure: Examples of conjunctival involvement. Image courtesy of Dr. Jonathan Trobe.

Figure: TEN. Image courtesy of Dermnet. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Urticaria Associated with Anaphylaxis

Urticaria is described as pink to erythematous wheals (hives) that are pruritic and vary in shape and size. By definition, an urticarial lesion should change in its morphology or resolve within 24 hours. Acute urticaria (<six weeks of duration) is typically benign, however, when a child is experiencing anaphylaxis, an urticarial rash is the typical cutaneous manifestation. Anaphylaxis is a potentially fatal disease that occurs after exposure to an allergen and causes a massive release of histamines, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes. Diagnosis is largely clinical and consists of the development of signs/symptoms within minutes to hours after exposure. Such signs/symptoms include hypotension, cutaneous manifestations (urticaria, angioedema), respiratory signs (stridor, wheezing), and persistent gastrointestinal symptoms (emesis, abdominal pain).

Treatment of urticaria can include oral antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, or newer generation H1 blockers such as loratadine and cetirizine may also be used as they have a less sedating profile. Systemic corticosteroids are usually reserved for severe disease and can be associated with a rebound flare upon cessation. The first-line treatment of anaphylaxis includes IM epinephrine. In addition, one can also consider systemic corticosteroids, diphenhydramine, and H2 blockers such as famotidine as second-line therapy for anaphylaxis for severe or refractory cases.

Figures: Urticaria. Images courtesy of Dermnet. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Henoch-Schonlein Purpura (HSP) or IgA Vasculitis

HSP is a type of vasculitis of unknown etiology. A child with HSP will typically have a non-thrombocytopenic palpable purpuric (non-blanching) rash in the dependent areas such as lower extremities and buttocks. However, the rash can also present in the upper extremities, thorax, and face. The rash may also be urticarial wheals or a maculopapular rash. Other associated symptoms may be arthritis, arthralgia, edema, and abdominal pain. Intussusception can occur in 2-3% of patients and 20-50% of patients will have renal involvement ranging from microscopic hematuria to glomerulonephritis. Evaluation of a child with HSP should include a urinalysis to assess for hematuria and proteinuria, checking blood pressure to assess for hyptertension, as well as laboratory workup to evaluate renal function. There is no specific treatment for the rash as it will self-resolve. NSAIDS can be given for arthralgia and arthritis. Corticosteroids have been shown to ameliorate GI symptoms. Hospitalizations may be required for pain management and or renal dysfunction.

Figures: HSP. Images courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

Figure: HSP Purpura. Image courtesy of Profrofrof. Used under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Scarlet Fever

Scarlet fever is the association of a toxin-mediated exanthem from group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus and pharyngitis or a skin wound. The rash is known as scarlatina. Children four-eight years of age are most affected and typically present with fever, pharyngitis, headache, and a rash. The hallmark of scarlatina is a widespread erythematous pinpoint papules described as a sandpaper rash, the presence of petechiae in the axillary folds or antecubital fossa known as Pastia lines, prominent papillae of the tongue (strawberry tongue), and red cheeks with circumoral pallor. Confirmatory tests include rapid strep throat culture and/or throat strep culture.

Figure: Strawberry tongue. Image courtesy of Afag Azizova. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Figure: Red cheeks with perioral pallor. Image courtesy of Alicia Williams. Used under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Figure: Sandpaper-like rash. Image courtesy of Alicia Williams. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license.

Figure: Pastia lines in antecubital fossa. Image courtesy of Dr. Natalie Yapo. Used with permission.

Tinea Corporis/Capitus

Tinea capitus is an infection of the scalp caused by a dermatophyte. The infection may have different characteristics depending on the type of dermatophyte infection. The infection may result in circular patches of alopecia and scaling. Black dots may be seen due to remaining hair remnants in the follicle. The infection may resemble seborrheic dermatitis (dandruff) in that there are patchy white to gray scaling with minimal alopecia. An inflamed tinea capitus lesion referred to as a kerion will present with a tender, erythematous boggy mass. Tinea capitus is often associated with suboccipital or posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. Typically, this infection is clinically diagnosed but the gold standard for diagnosis is a fungal culture of a scale or hair fragment. Treatment of tinea capitus is an oral antifungal such as griseofulvin for six-eight weeks. Terbinafine is often used for refractory cases. An antifungal shampoo should also be used twice a week to decrease spread of infection. Oral steroids should be considered as an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of a kerion.

Figure: Tinea capitus. Note the patch of alopecia with black dots. Image used under the GNU Free Documentation license.

Figure: Kerion. Note the boggy erythematous appearance with associated alopecia. Image courtesy of Grook da Oger. Used under the licensia de documentación libre GNU.

Tinea corporis is a cutaneous infection caused by a dermatophyte and causes annular lesions with a raised erythematous border and central clearing with associated scaling. A topical antifungal imidazole cream or ointment such as clotrimazole or topical allylamine such as terbinafine can be used for treatment. Oral agents are reserved for extensive disease.

Figure: Tinea corporis. Note the erythematous raised border with central clearing. Image courtesy of the CDC, Dr. Lucille Georg. Image is in the public domain.

Viral Exanthem

Viral exanthems are typically erythematous macules and papules in a child with a prodrome of upper respiratory infection symptoms, fever, and/or gastrointestinal symptoms. The majority of viral exanthems will be non-specific for a particular virus. There are a few viruses that have a classic rash description as well as commonly associated signs and symptoms. Erythema infectiosum or fifth disease due to Parvovirus B19 may cause a "slapped cheek" appearance with a lacy reticular rash. Roseola infantum, also known as exanthem subitum, typically occurs in children six months-three years of age and is characterized by three-five days of high fevers followed by a macular papular rash that occurs after the fever subsides.

Figure: Erythema infectiosum. Note the bright red "slapped cheeks." Image courtesy of Andrew Kerr. Image is in the public domain.

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD)

HFMD is a viral exanthem most often caused by group A and B coxsackieviruses and enterovirus 71 in the late summer and early fall. Typically, the child will be febrile with URI symptoms. The hallmark exanthem noted with HFMD are vesicles and small, shallow ulcerations on an erythematous base in the oral cavity, palms, and soles. Oral lesions will be located on the uvula, palate, tonsillar pillars, buccal mucosa, and tongue, and can be painful. Apart from the palms and soles, other cutaneous lesions may occur around the mouth, buttocks, perineum, elbows, knees, and lateral aspects of the hands and feet. If the child only has oral involvement, the rash is termed herpangina. Diagnosis is made clinically, and treatment includes supportive care, analgesics for pain, antipyretics, and oral rehydration. In certain cases, the oral painful lesions may lead to dehydration requiring admission for intravenous hydration and pain management.

Figure: HFMD rash of the feet. Image courtesy of Ngufra. Used under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure: Perioral HFMD rash. Image courtesy of MidgleyDJ. Used under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum

Erythema Toxicum is a benign rash of unknown etiology that occurs in 50% of full-term newborns. Typically, the rash will erupt 24-48 hours after birth and may last up to seven days. The rash is described as erythematous, blotchy patches with an associated papule, pustule, or vesicle. The rash typically spares the palms and soles. Diagnosis is largely made clinically. A Wright stain of the vesicle or pustule's fluid will reveal largely eosinophils. No treatment is needed other than reassurance.

Figure: Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum close up. Image courtesy of A.D.A.M. Image is public domain.

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis

Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis may affect up to 5% of Black infants. At birth, pustules are noted in various areas of the body including the palms and soles. Ruptured pustules will leave a hyperpigmented macule often with a scaly rim. Diagnosis is largely made clinically. A Wright stain of the pustule's fluid will reveal largely neutrophils. No treatment is needed other than reassurance. The pustules will typically resolve in several days, whereas the hyperpigmented macules will subside in three-four months.

Figure: Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis. Image courtesy of Dermnet. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Figure: Transient Neonatal Pustular Melanosis. Image courtesy of Gzzz. Image used under the CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis Rosea is a papulosquamous (papules and scales or scaly papules and plaques) rash that is self-limited. A herald's patch is the initial lesion seen in 80% of patients and will have similar features of tinea corporis in that it is an oval or circular erythematous patch with central clearing and a scaly rim. Within two-four weeks, the herald's patch will be followed by an eruption of erythematous papules and oval plaques with scales typically located on the torso. On the back, the rash has a "Christmas tree" distribution. The oval plaques' long axis will be parallel to the lines of skin stress. Of note, in children with a darker complexion, pityriasis rosea will have different features. The rash may be more papular with few plaques, as well as there may be an inverse distribution of the rash involving the neck, proximal extremities, groin, and axillae rather than the torso. The rash may be pruritic. There is no specific treatment, but exposure to sunlight may hasten the resolution of the rash.

Figure: Herald's Patch. Note erythematous patch with central clearing. Image courtesy of Dermnet. Image used under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand).

Figure: "Christmas tree" distribution of erythematous plaques. Image courtesy of Dr. James Heilman. Image used under the CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figures: Pityriasis rosea in Black child. Note scaly papules and plaques. Pictures courtesy of Dr. S. Margaret Paik. Used with permission.

- The appearance, distribution, and associated symptoms are paramount in figuring out the etiology of a rash and can help narrow your diagnosis.

- Recognizing an ill-appearing vs well-appearing child is imperative when considering a life-threatening rash.

- Rashes that are life-threatening - such as meningococcemia, TEN, SJS, herpetic lesions involving the eye, widespread eczema herpeticum, and urticarial rash with anaphylaxis - require timely recognition and intervention.

- Urticaria with no other associated symptoms or signs is often benign and requires symptomatic care.

- When urticaria is associated with hypotension, persistent GI symptoms, and/or respiratory signs, a diagnosis of anaphylaxis should be considered.

- Children with suspected HSP should be screened for renal involvement with a urinalysis, serum renal function, and blood pressure monitoring.

- Tinea corporis can be treated by a topical antifungal, whereas tinea capitis is treated by an oral antifungal.

- Viral exanthems are typically non-specific, usually require supportive care, and usually resolve on their own.

- Campbell RL, Li JT, et al. Emergency Department Diagnosis and Treatment of Anaphylaxis: A Practice Parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunology. 2014.

- Kane KS. Color Atlas & Synopsis of Pediatric Dermatology. McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009. Print.

- Krowchuk DP, Mancini AJ. Pediatric Dermatology: A Quick Reference Guide. 2nd Ed. Section of Dermatology. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2012. Print.

- Lanzkowsky S, Lanzkowsky L. Henoch-Schoenlein Purpura. Pediatrics in Review. 1992. Print.

- Weston WL, Lane AT. Color Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology. Mosby Year Book. 1991. Print.