GI Bleed

Author Credentials

Updated: September, 2019

Case Study

68-year-old man presents with vomiting coffee ground emesis. He has a history of alcohol use disorder and has been seen in the ED in the past for bleeding hemorrhoids. VS: HR 110, BP 85/45, RR 20, O2 Sat 100% He is pale and diaphoretic, ill appearing. Abdomen is soft, nontender, but distended. Upon arrival to the ED, the patient has an episode of hematemesis, witnessed by the staff.

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the student will be able to:

- List common causes of a Gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.

- Discuss the initial assessment, management and disposition of a patient presenting to the Emergency Department with a GI bleed.

- Explain the indications for blood transfusion in a patient with a GI bleed, including packed red blood cells, platelets, and administration of clotting factors or other reversal agents for anticoagulants.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common presentation in the Emergency Department and can involve any bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. In the United States, it is estimated that about 540,000 hospitalizations occur each year due to GI bleeding.

The differential diagnosis of GI bleeding is generally categorized into Upper or Lower GI Bleeds, based on whether the bleeding occurs anatomically above or below the Ligament of Treitz. Bleeding from the Upper GI tract is 4 times more common than bleeding from the Lower GI tract. The list of potential causes by location are included in Table.1.

By Diagram of the stomach, colon and rectum from public domain source at http://www.cancer.gov/cancerinfo/wyntk/colon-and-rectum - http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/colon-and-rectum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=283275

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

GI bleeding can be categorized as acute or subacute. Acute GI bleeding often results in the need for more urgent intervention and stabilization than subacute bleeding. Initial management regardless of the source or acuity is stabilization of the patient, and then attempting to manage the source of bleeding depending on the etiology.

Initial management of a patient with an acute GI bleed include:

1. Primary Survey

Secure the airway – assess for any blood in the airway and adequacy of respirations. Intubate as needed for airway protection in the setting of massive hematemesis or altered mental status due to hypovolemia.

Oxygen – 2L via Nasal Cannula at minimum.

Insert bilateral, 18-gauge (minimum), upper extremity, peripheral intravenous lines

Volume resuscitation - Replace each milliliter of blood loss with 3 mL of crystalloid fluid for initial resuscitation. If the patient is acutely unstable after crystalloids or if the bleeding is visible and profuse, consider transfusing un-crossmatched blood while a type and cross is being performed. If your hospital has a massive transfusion protocol and you think it may be needed due to large volume blood loss, activation of this protocol after the initial evaluation should be considered as well.

2. Obtain an adequate History and Physical Exam

- Any anticoagulant or antiplatelet or NSAID use?

- Alcohol use history or variceal bleeding in the past?

- Prior ulcers or bleeding history?

- Recent colonoscopy?

3. Labs – ensure that the following labs are collected from the patient

- Type and crossmatch blood

- Complete blood count with differential

- Basic metabolic profile, paying attention to the BUN

- Liver function tests, albumin, alcohol level (if appropriate)

- Coagulation profile

- Lactic Acid

- ABG (if the patient appears acutely ill)

Presentation

Bleeding can range from microscopic levels causing subacute or chronic presentations, detectable only by fecal occult blood sampling, to the more dramatic acute presentations of massive hemorrhage that is visible in the stool or vomitus and can be life threatening.

The patient history may help you identify the source of bleeding. Hematemesis (red blood in emesis) or coffee ground emesis usually indicates upper GI bleed. Melena (dark or tarry stools) occurs in about 70% of patients with upper GI bleed and 30% of lower GI bleed. Hematochezia (blood in the stool) can be due to LGIB or an UGIB with significant bleeding and increased GI motility. In one meta-analysis, Srygley et al reported that a patient report of melena had a likelihood ratio of UGIB of 5.1-5.9, melanotic stools on exam had a likelihood ratio of 25. Table 2 demonstrates the difference in presentation between upper and lower GI bleeding.

While a focused H&P is critical, it is also important to look for physical exam findings that may be secondary and related to other pathologies. These can include signs of liver disease in a patient you suspect esophageal varices to be the cause of UGIB – ie Jaundice, Scleral Icterus, Hemorrhoids, etc. Likewise, those with LGIB who presents with weight loss and decreased appetite should be evaluated for occult malignancy.

There are several clinical decision rules that can aid in determining risk from GI bleeding. They are briefly discussed below.

AIMS65 is a scoring system that uses data available prior to endoscopy to predict inpatient mortality among patients with upper GI bleeding. The study found that five factors were associated with increased inpatient mortality: https://www.mdcalc.com/aims65-score-upper-gi-bleeding-mortality

- Albumin less than 3.0 g/dL (30 g/L)

- INR greater than 1.5

- Altered Mental status (Glasgow coma score less than 14, disorientation, lethargy, stupor, or coma)

- Systolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or less

- Age older than 65 years

A more complex scoring system, the Glasgow Blatchford Bleeding Score, also exists for the pre-endoscopic stratification of GI bleed presentations and has been demonstrated as an accurate risk score for predicting need for clinical intervention, or death, after upper gastrointestinal bleeding, according to an international multicenter study: https://www.mdcalc.com/glasgow-blatchford-bleeding-score-gbs

Diagnostic Testing

Workup includes the history, physical exam and lab findings mentioned in the initial actions section above as well as the following:

Labs: The laboratory studies often serve as a baseline for future comparison. They should also be compared with previous labs if they are available, to assess the patient’s prior baseline hemoglobin.

Chest radiography – evaluate for perforated viscus

EKG – assess for comorbidity and end organ damage, especially if the patient is unstable

Nasogastric lavage - In the hemodynamically unstable patient with an UGIB, it is unclear that NG tube insertion is helpful as these patients require urgent endoscopy after resuscitation. In the stable patient without ongoing hematemesis, aspiration of fresh red blood can be indicative of a high-risk lesion, but in general NG lavage has significant associated risk factors and is generally not recommended except to facilitate time to endoscopy.

Endoscopy – to localize and stop the source of bleeding in upper GI bleeds.

CT Angiography with Interventional Radiology (if bleeding persists but the source is not visible on endoscopy).

Nuclear Medicine Bleeding Scan can be considered for patients with moderate lower GI bleeding (stable vital signs with or without administration of blood products). In particular, this test can be useful in a patient with recurrent GI bleed, with a negative colonoscopy and endoscopy in the past for similar bleeding episode. A positive scan can guide surgical or interventional radiology management of a chronic, recurrent GI bleed.

Treatment

Treatment options for acute GI bleeds depends on the source of the bleeding, but in general can be divided into blood transfusions, pharmacologic management and consultations.

Blood Transfusion – informed consent should be obtained prior to administration of these blood products to the best of one’s ability, or consideration should be given for emergency consent if the patient is too unstable to give consent or proxy is not readily available to consent.

Packed Red Blood Cell (PRBC) Transfusion

The primary indication for blood transfusion is hemorrhagic shock despite IV fluid resuscitation. If a patient is actively bleeding, particularly with abnormal vital signs, earlier transfusion may be indicated despite the value of hemoglobin as the blood volume may not have had time to equilibrate.

Indications to consider immediate PRBC transfusion include:

- Massive upper or lower GI bleed (e.g. passing 1000 mL maroon-colored thin liquid stools every 20-30 minutes or an NG tube with a constant output of blood)

- Hemoglobin dropping at a rate of 3g/dL over 2-4 hours in the setting of active bleeding

- Hemoglobin less than 7 in the setting of active bleeding

- Anemia induced end-organ injury (i.e. EKG changes or lab results indicating cardiac ischemia)

Transfusion should also be considered in patients with acute or subacute bleeding and a hemoglobin of 7 g/dL, or symptomatic anemia (including dyspnea, lightheadedness, and chest pain) at a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL or 9 g/dL. The hemoglobin concentration always needs to be viewed in context to the clinical condition of the patient. If the GI bleed is acute, the hemoglobin may be relatively normal despite significant blood loss. If the GI bleed is subacute or chronic, a lower hemoglobin may be seen in a hemodynamically stable patient. In addition, keep in mind the possibility of a post resuscitation dilutional anemia that can occur after administration of a large volume of IV fluids.

https://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/co525904/blood-plasma-bag-labelled-o-containing-theatrical-blood-blood-plasma-bag

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence

Be mindful to avoid overtransfusion in patients with suspected variceal bleeding, as it can precipitate worsening of the bleeding. In general, transfusion should aim to raise the level of the hemoglobin to a goal of 9 g/dL.

Platelets

The indication for platelet transfusion in the setting of active acute GI bleeding is for platelet counts <50,000/microL. Below this level, many GI doctors will delay endoscopic management given the risk of further bleeding due to the thrombocytopenia. Patients taking anti-platelet medications such as aspirin or clopidogrel do not need platelet transfusions, but the decision to discontinue or hold the medication should be done in consultation with cardiology.

Reversal of Anticoagulation

For patients taking an anticoagulant medication (warfarin, anti-factor Xa inhibitor or other blood thinner) who present with GI bleeds with an INR > 2, transfusion of the appropriate reversal product should be considered.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or cryoprecipitate should be given to reverse warfarin in the setting of life-threatening bleeding. Patients who have milder GI bleeding on warfarin that are more hemodynamically stable can be managed with IV or oral Vitamin K depending on the level of the INR.

However, the reason for anticoagulation should be considered and the risks and benefits of reversal should be weighed to determine if the patient needs to remain anticoagulated. Often this decision is not always clear cut. For example, in a patient with a mechanical heart valve on warfarin, the risk of reversal may be greater than the risk of bleeding, particularly if the source of GI bleed can be identified and treated. Conversely, if a patient had a prior DVT and is on warfarin, it would be reasonable to reverse the coagulopathy with vitamin K immediately regardless of the source of bleeding.

The newer oral anticoagulants like dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban are more difficult to reverse than warfarin. In recent literature, the rates for GI bleeds have been noted to be highest for patients on rivaroxaban and lowest for patients on apixaban.

- Prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) may be effective with all three medications at variable levels.

- Dabigatran (Pradaxa) can be reversed with idarucizumab (Praxabind) for life-threatening bleeding. It can also be dialyzed if necessary.

- Apixaban (Eliquis) and Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) are anti-factor Xa inhibitors and can be reversed with 4-factor PCC (KCentra) for life threatening bleeding as well.

The indication for reversal with the monoclonal antibody is often reserved for life-threatening bleeding due to costs and limited supplies.In patients with cirrhosis and likely variceal bleeding, FFP or clotting factor replacement should be considered, as these patients may not be synthesizing enough intrinsic clotting factors to allow for proper coagulation. The INR is not always a reliable measurement of the degree of coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Blood pressure should also be monitored in the patients so as to not over-correct hypotension as hypertension may decrease clot stability during the process of clot formation.

Pharmacologic Management

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Generally, PPIs are first line for acid suppression in patients with upper GI bleed. In a low-risk patient who is likely to be admitted to the hospital, an empiric IV PPI can be started (i.e. Pantoprazole 40 mg IV BID) and continued until the source of bleeding is found. In a patient with more severe, active bleeding, or in the case of a patient with multiple comorbidities, a high dose IV bolus followed by a continuous infusion of Pantoprazole (80 mg bolus followed by 8 mg/ hour drip) can be considered as well, particularly in the case of concern for peptic ulcer disease as the source of GI bleed.

Somatostatins: In patients with known or highly suspected variceal bleeding, octreotide (synthetic somatostatin) causes vasoconstriction of splanchnic blood flow resulting in decreased secretion of gastric acid and pepcin and can be administered as an IV bolus followed by an IV drip. There is no evidence to support its use in non-variceal upper GI bleeds.

Administration of antibiotics has been shown to reduce mortality by about 20% in patients with cirrhosis who present with GI bleeds. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommends considering ceftriaxone as first line management and ciprofloxacin as second line treatment if ceftriaxone is contraindicated.Typical dosing of ceftriaxone is 1g.

Consultants

- Early consultation with Gastroenterology for endoscopic hemostatic therapy for bleeding ulcers and varices

- Indications for surgical consult in GIB

- Active persistent bleeding with hemodynamic instability and/or despite transfusion with multiple units of blood products.

- If a perforated ulcer is suspected, the patient might benefit from endoscopy in the operating room so that if resection/repair is needed, this can be rapidly performed.

- Similarly, if there is concern for massive lower GI bleeding, the patient may go to the operating room for partial small bowel resection or colostomy.

- Interventional Radiology consultation for those patients who are too high risk for surgical management or for those who will need angiography.

Disposition:

Intensive Care Unit – consideration for disposition to the ICU should be given to those patients who present with altered mental status requiring intubation, have persistently unstable vital signs, have a fast rate of bleeding, and those with multiple risk factors for increased mortality as identified by the AIMS65 score mentioned above.

The need for increased nursing care with multiple continuous drips (ie blood transfusion, ppi gtt, crystalloid, etc) or advanced procedural sedation for endoscopy should prompt admission to the ICU as well.

Medical Floor – Hemodynamically stable patients who require blood transfusions and further monitoring of their blood counts can be safely admitted to the medical floors. General recommendations suggest that patients should be hospitalized for 72 hours to monitor for rebleeding, since most rebleeding occurs during this time.

Home - Some patients with a mild GI bleed can be dispositioned to home. In general, these patients will be relatively asymptomatic, have stable vital signs, no more than a mild anemia, and no active bleeding besides a positive stool guaiac or blood streaked emesis (presumably from Mallory Weiss tears which have stopped bleeding). They should have prompt follow-up identified for monitoring of their hemoglobin and referral to gastroenterology for endoscopy or colonoscopy as appropriate.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Identify the source of bleeding as soon as possible with an accurate history and physical exam.

Initiate and expedite lifesaving blood transfusions and reversal agents for anticoagulant use for acute bleeding.

Foley catheter placement for continuous evaluation of urinary output as a guide to renal perfusion

Call GI as soon as possible for early endoscopic management in patients acute UGIB. Early endoscopy has been associated with reductions in the length of hospital stay, rate of recurrent bleeding, and the need for emergent surgical intervention.

Dieulafoy’s lesion – large submucosal arterial malformation that usually occurs within 6 cm of the GE junction in the stomach and can cause massive GI hemorrhage if it ruptures.

Heyde’s syndrome – lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to angiodysplasia in patients with aortic stenosis. The severity of the aortic stenosis is thought to create an acquired von Willebrand's disease state. The presence of the GI bleeding should prompt you to listen to the patient’s heart sounds and consider getting an echocardiogram, since resolving the aortic stenosis has been shown to improve the von Willebrand’s disease and thus the GI bleeding.

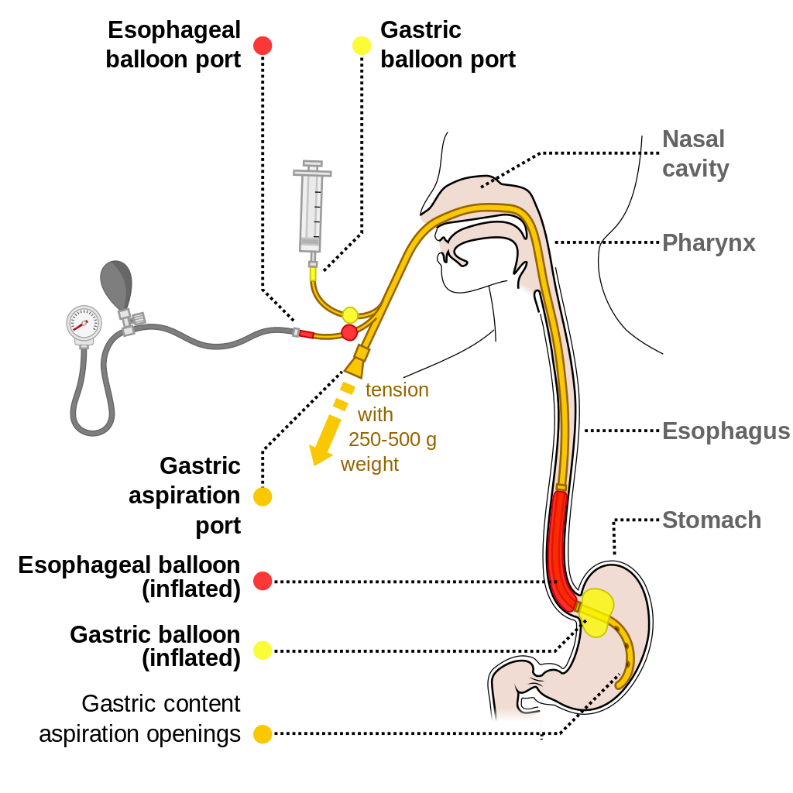

Consider emergent esophageal balloon tamponade with Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for massive upper GI bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sengstaken-Blakemore_scheme_EN.svg : Common creative license

Case Study Conclusion

Primary survey was conducted and the patient was found to be oxygenating and ventilating appropriately with normal mental status, so oxygen 2L via NC was placed and he was given 2L NS via l6 gauge IV catheters which only temporarily raised his blood pressure over 90/60. Labs were drawn and sent for Type and Cross, CBC, CMP, coags, etc. The patient was found to have a hemoglobin of 6 mg/dL and an INR that was elevated to 2.1. The patient was consented to a PRBC transfusion and PCC transfusion, after consultation with cardiology to decide if the patient could be taken off his anticoagulant medication. He was admitted to the ICU where endoscopy was performed after the coagulopathy was reversed and revealed bleeding esophageal varices. The patient was monitored in the hospital for 72 hours and had no further rebleeding and was discharged home. He was set up for follow up with Gastroenterology and with Cardiology for determination of when to restart his anticoagulant medication. https://www.mdcalc.com/has-bled-score-major-bleeding-risk

References

Blatchford O, et. al. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Lancet 2000.

Cerulli M, Iqbal S. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Treatment and Management. Medscape. March 2016. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/187857-overview#a1 Accessed on March 20, 2019.

Kim BS, Li BT, Engel A, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding: A practical guide for clinicians. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5(4):467-78. PMID: 25400991

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Association of Oral Anticoagulants and Proton Pump Inhibitor Cotherapy With Hospitalization for Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Bleeding. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2221–2230. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.17242

Srygley FD, et al. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed?. JAMA 307.10 (2012): 1072-1079.

Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, et al. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec;74(6):1215-24.

Saltzman J. Approach to Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Adults. UptoDate. Updated February 12, 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-acute-upper-gastrointestinal-bleeding-in-adults#H14 Accessed on March 20, 2019.

Vincentelli A, Susen S, Le Tourneau T, Six I, Fabre O, Juthier F, Bauters A, Decoene C, Goudemand J, Prat A, Jude B (2003). "Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in aortic stenosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (4): 343–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022831. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 12878741.FOAM-ED:

Life In The Fast Lane, Upper GI Bleed and Lower GI Bleed

YouTube Video, Upper GI Bleed and Lower GI Bleed