Abscess incision and drainage

Author Credentials

Author: Heidi Ludtke, MD, Medical College of Wisconsin (initial);

2023 Update Author: Pollianne Ward Bianchi, MD, Drexel University College of Medicine

US images credited to: Melissa Yu, MD and Crozer Health Sono Division

Editor: David Manthey, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Section Editor: William Alley, MD, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Updated: January 6th, 2023

Case Study

A 24-year-old healthy male comes to the Emergency Department with a chief complaint of “boil.” He reports that he developed a pimple on his forearm 2 days ago that has become swollen and gotten progressively worse. He reports pain and tenderness of the area. He denies fever, chills, trauma to the area, or IV drug use. There has been no drainage. He has been taking ibuprofen for pain and using warm compresses on the area.

His vital signs are: BP 134/78 HR 100 RR 16 Temp 99.0 Sat 100% on RA

On exam, he has a 3 cm area of erythema and induration on his left forearm that is firm and tender to palpation. There appears to be a papule in the center of the area.

Objectives

- To understand the indications and contraindications for incision and drainage (I&D) of abscesses in the ED

- To describe the procedure of abscess I&D, including appropriate anesthesia.

- To recognize the importance of after care and patient education about abscess I&D.

- Recognize the importance of after care and patient education about abscess I&D.

Introduction

Abscesses are among the leading presentations of skin and soft tissue infections seen in the Emergency Department. What may begin as a localized superficial cellulitis after a compromise of the epithelium can result in an abscess. Necrosis and liquefaction occur as cellular debris accumulates and becomes loculated and walled-off as a collection of pus beneath the epidermis.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Evaluate the patient’s A, B, C’s and initial vital signs as with any patient presenting to the Emergency Dept. Most patients with abscesses requiring incision and drainage will be clinically stable and not require resuscitation. However, abscesses in close proximity to the airway, such as submental, oral or neck abscesses should be carefully assessed for airway compromise and need for prophylactic intubation.

Presentation

Physical examination will show a tender, erythematous, warm, fluctuant mass such as that noted in Figures 1 and 2. Fluctuance can be described as a tense area of skin with a wave-like or boggy feeling upon palpation; this is the pus which has accumulated beneath the epidermis. Without adequate evacuation of this pus, the infection will continue to accumulate and can lead to disseminated or systemic infection. Because there may be surrounding cellulitis, induration can make an abscess less apparent on physical exam.

Figure 1. Abscess in an African-American patient (Image courtesy of: Heidi Lutdke, MD in original chapter)

Figure 2. Abscess on lighter colored skin with fluctuance (Image courtesy of: Maxwell Cooper, MD and Crozer Sono Division. Obtained with patient permission)

Diagnostic Testing

Well appearing patients with simple abscesses do not require any labs or imaging. In patients with systemic symptoms or concerns for complications, such as diabetics or IV drug users, labs may be indicated. A CBC, Basic Metabolic Panel, and Lactate can guide disposition in those cases, but most often, an incision and drainage is still performed.

Wound Cultures

Staphylococcus aureus, especially community-acquired methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA), is the most common cause of abscesses in the Emergency Department (ED) population. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococci most often causes cellulitis without abscess. Abscesses associated with specific environmental exposures may be caused by different organisms, such as Eikenella or Pasteurella after an animal bite, Vibrio after saltwater exposure and Pseudomonas after hot tub exposure. Anaerobic bacteria can contribute to abscesses in perineal or oral regions. Abscesses in IV drug users most frequently contain strep and staph but may also contain anaerobic and gram negative bacteria due to poor hygiene or licking of needles.

Most abscesses do not require wound culture as it is assumed that the etiology is MRSA. However, cultures should be considered in complicated abscesses, those with IV drug abuse, non-healing abscesses, or abscesses in the genital region.

Imaging

Bedside ultrasound can be helpful in differentiating a simple cellulitis from an abscess which requires drainage and has been shown to decrease treatment failures when used in conjunction with incision and drainage. Ultrasound may aid in planning the procedure and visualizing full evacuation of the abscess cavity. In one study, treatment failures were more likely to occur in larger abscesses that were assessed with physical exam alone prior to incision and drainage. Ultrasound can also show foreign bodies, such as in patients who inject IV drugs and may have a needle break off.

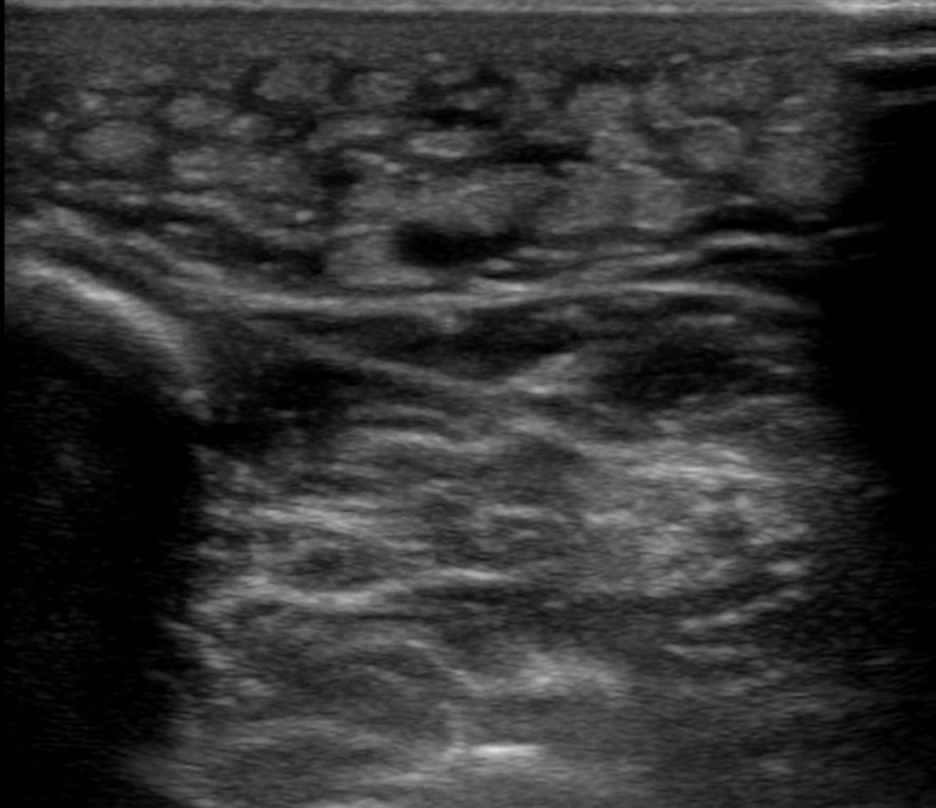

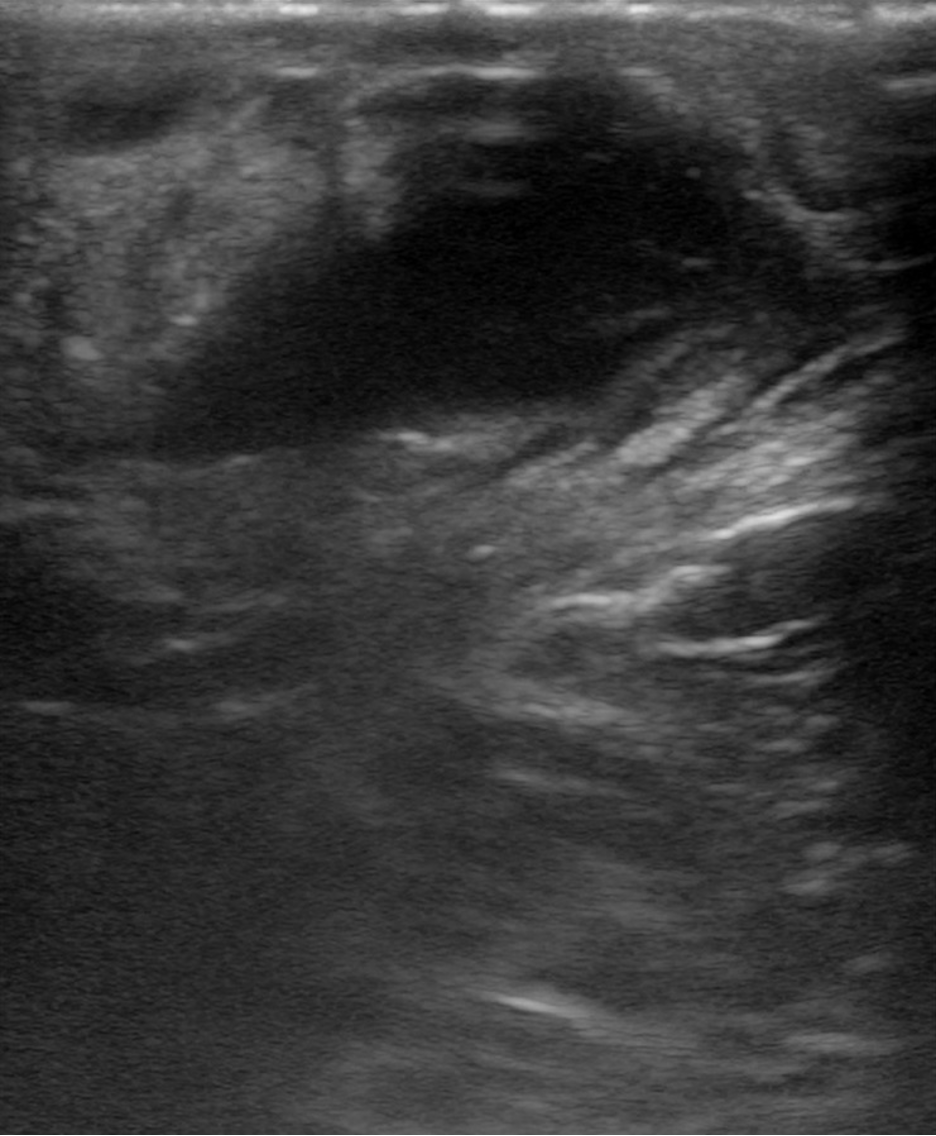

When reviewing ultrasound images, areas of cellulitis are hyperechoic with thickened lobules of subcutaneous fat interwoven with hypoechoic strands of fluid; this is referred to as “cobblestoning.” (Figure 3) In contrast, abscesses have a more well-defined collection of anechoic fluid sometimes containing loculations and whirling debris. (Figure 4) There may be overlying findings of cellulitis or a hyperechoic rim.

Figure 3. Ultrasound image demonstrating cobblestoning often seen in cellulitis (Image courtesy of Melissa Yu, MD and Crozer Sono Division. Obtained with patient permission)

Figure 4. Ultrasound image demonstrating fluid collection consistent with abscess (Image courtesy of: Melissa Yu, MD and Crozer Sono Division. Obtained with patient permission)

If there is a localized area of induration but no fluctuance on exam or fluid collection on ultrasound, home care with application of heat via warm compresses or soaks along with antibiotics may be attempted. However, it may be the very early development of an abscess which will be ready to drain within 24-36 hours, so these patients should be well-educated on the signs of abscesses and reasons to return to the ER for re-evaluation.

CT imaging may be considered for abscesses that are larger, in sensitive areas or those that are difficult to access. Abscesses in the neck or submental area, scrotum or perineum, rectum, or sternoclavicular area may extend to deeper structures and should have a lower threshold for CT.

Treatment

Indications

The indication for abscess incision and drainage is a fluctuant abscess with a large enough pocket of purulence to drain.

There are few contraindications to this procedure, however, certain situations should prompt consideration of consultation of general or specialty surgical services: large or complex abscesses, those in sensitive areas (face, hand, breast, genitalia) or in regions in close proximity to structures such as blood vessels. Abscesses that do not resolve despite repeated adequate drainage should prompt consideration of a retained foreign body, underlying osteomyelitis or septic arthritis, unusual organisms such as fungi or mycobacteria, or immunodeficiency of the patient (i.e., uncontrolled or undiagnosed diabetic).

Occasionally, needle aspiration may be attempted by the Emergency Physician or subspecialist in patients with smaller abscesses. However, the success rate of needle aspiration is lower for multiple reasons: the inability to aspirate pus does not necessarily mean there is no purulence to be drained and some will later require repeat drainage (either again by needle or later by I&D.)

Materials/supplies

- Personal protective equipment (eye-shield, mask, gloves)

- Injectable anesthetic such as lidocaine +/- epi, bupivacaine

- 10cc syringe, 18g & 25g needles

- #11 blade scalpel

- Curved hemostat

- 4×4 gauze pads

- Saline and large syringe (20 cc or larger) with 18-gauge angiocatheter or splash-shield

- Thin packing gauze such as iodoform

- Scissors

- Forceps

- Tape

Technique

Preparation

Prepare the skin by cleaning with either alcohol swabs, betadine or chloraprep. Clean gloves and sterile equipment should be used, though this is a procedure that is impossible for sterility to be maintained (given the draining of infected contents.)

Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended in patients at high risk for infective endocarditis (prosthetic valves, previous endocarditis and certain cases of congenital heart disease or cardiac transplantation.)

Anesthesia & analgesia

Local anesthetic such as lidocaine or bupivacaine should be injected within the roof of the abscess where the incision will be made. Care should be taken to avoid injecting anesthetic into the abscess cavity, as this will increase pressure (and thus pain for the patient) and is unlikely to successfully anesthetize. Many emergency physicians do a “field block” by injecting a ring of anesthetic into the subcutaneous tissue approximately 1cm around the circumference of the abscess. However, the maximum safe dose of anesthetic should not be exceeded. A regional block should be considered in larger abscesses that will require a large dose of anesthetic.

Achieving adequate anesthesia of abscesses can be challenging, as even the best technique will prevent the sensation of sharp but not the tension and pressure of breaking up adhesions. Parenteral or oral analgesics should be given in the ED prior to beginning the procedure. Depending on the abscess size and location, as well as the patient’s individual characteristics and preferences, procedural sedation may be necessary.

A video demonstrating a lidocaine injection can be found here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udzkzhqjy6k

Incision and Drainage

Classic Method

Start by finding the area that is the most fluctuant over the pocket of purulence. With a number 11 blade scalpel, stab into the abscess straight down and make a linear incision across the diameter of the fluctuant area. Ensure an appropriate depth to reach the cavity of purulence as in Figure 5 and 6. It’s also important to ensure the length of the incision will allow adequate drainage and room to use hemostats; this is typically between 2/3rd to the full length of the diameter of the fluctuant area, at least 1 cm. After initial drainage of purulence, probe the incision with a hemostat or a needle driver, opening them up at varying angles in a 360 degree range within the cavity to break up any loculations.

Figure 5. Abscess after being incised (Image courtesy of Heidi Lutdke, MD)

Figure 5. Abscess after being incised (Image courtesy of Heidi Lutdke, MD)

Figure 6. Use of hemostats to break up loculations (Image courtesy of Heidi Lutdke, MD)

Figure 6. Use of hemostats to break up loculations (Image courtesy of Heidi Lutdke, MD)

Normal saline is often used via a syringe (which may have an attached angiocatheter or splash-shield) to irrigate the cavity, though current evidence suggests this is of questionable benefit. Be sure that the effluent is draining from the cavity and you are not just forcing saline and/or pus into deeper structures.

Packing the abscess cavity used to be a mainstay of incision and drainage. New literature suggests that this practice is not necessary for successful abscess healing and it causes significant discomfort to the patient and repeated follow up visits. However, some emergency physicians still opt to pack larger abscess cavities with the intent of allowing adequate drainage by preventing premature closure in the days following I&D. Thin, continuous, ¼ inch plain or iodoform gauze should be placed gently into the cavity with 2 cm extruding and taped to the skin. The cavity should not be packed tightly as this increases pain for the patient and enough packing is only necessary to keep the cavity open to prevent synechiae. The wound can then be covered with a dressing.

A video of the classic method can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwgNdrA18fM

Loop Drainage Method

Within the last few years, a newer method of incision and drainage using two incisions and a loop has been introduced with studies showing non-inferiority in healing and several advantages over the classic incision, drainage, and packing method.

You will need a thin strip of material such as tubing from a butterfly lab draw kit, or an IV tourniquet cut to about ⅛ of an inch. To start, make a small incision at the periphery of the area of induration or abscess pocket with a #11 blade scalpel. Then insert a hemostat and break up any loculations as with the classic method. With the hemostat still inserted, use the tip to tent the skin on the opposite edge of the abscess cavity. Next, use the scalpel to make a small incision over the hemostat tip and poke it through. Feed the tubing or strip through and tie it loosely in a double knot. Irrigate the cavity as with the classic method.

A video of the incision and loop method can be found here: https://www.aliem.com/trick-of-trade-incision-and-loop/

Post-procedure care

For many abscesses, post-procedure care only involves supportive, local wound care. The initial I&D is usually curative and antibiotics are not required. Tetanus status should be inquired and administered if not up to date.

However, antibiotics are recommended for cutaneous abscesses (in addition to I&D) by the Infectious Disease Society of America in the following instances:

- Severe or extensive disease (i.e., abscesses in multiple sites, recurrences)

- Rapid disease progression with cellulitis

- Associated systemic illness (i.e., fever)

- Immunosuppression or complicating co-existing conditions

- Extremes of age

- Abscess in area that is difficult to drain (e.g., genitalia, face)

- Septic phlebitis

- Lack of response to I&D alone

Many studies have been done on the efficacy and need for antibiotics post I & D. There is evidence that there are fewer treatment failures in patients who receive antibiotics than those who only undergo I & D alone. In those cases in which antibiotic therapy is initiated, coverage should be directed at MRSA with antibiotics such as oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline or clindamycin. It’s important to be aware of local resistance patterns as community-acquired MRSA resistance to commonly used antibiotics, such as clindamycin, has increased in some regions. Cephalexin is often added if there is substantial surrounding cellulitis, as trimethoprim- sulmamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), in particular, does not have adequate coverage of

At home, patients may change their dressing as needed. They should soak the area in warm water or with warm compresses to encourage evacuation of all purulence. Pain should be treated at home with analgesics, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen. It is not unreasonable to give a few days worth of narcotic pain medication for large or complicated abscesses as they can be quite painful. Patients who had packing placed may be taught how to replace the packing as indicated. Occasionally, there may be residual purulence requiring further drainage and/or packing replacement. For this reason, a follow-up recheck visit in 1-3 days is recommended. The patient should be instructed to return to the ER sooner for worsening pain, swelling, erythema or for signs of systemic illness such as a fever, vomiting and myalgias.

Summary

Abscess I&D is one of the most commonly performed procedures in the ED. It is often curative and antibiotics are seldom indicated. Patients should be instructed on home care and the importance of a recheck in approximately 2 days.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Some abscesses may not be visibly fluctuant and use of US can detect hidden pockets of purulence that require drainage.

- Make sure your incision is long and deep enough to completely drain the cavity, introduce instruments, and irrigate.

- Incision and loop drainage is a newer technique that may provide less pain and better cosmetic outcomes when draining larger abscesses.

Case Study Resolution

The patient underwent successful incision and drainage in the Emergency Dept after bedside ultrasound showed a 3 cm x 2 cm x 2 cm deep abscess. The patient was instructed to return for a wound check to either his primary doctor or the Emergency Dept in 2 days.

References

- Gaspari, Sanseverino, A., & Gleeson, T. Abscess Incision and Drainage With or Without Ultrasonography: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2019; 73(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.05.014

- Holtzman LC, Hitti E, Harrow J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. Chapter 37 Incision and Drainage. 719-757. E3

- Lin, Brian. Parallel, Minimal Needle Insertion Technique (Adapted for Emergency Medicine) [video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udzkzhqjy6k. Published February 26, 2018. Accessed January 12, 2023.

- Lin, Michelle. Trick of the Trade: Incision and Loop Drainage of Abscesses [video]. https://www.aliem.com/trick-of-trade-incision-and-loop/. Published August 14, 2012. Accessed January 9, 2023.

- Mohamedahmed AYY, Zaman S, Stonelake S, et al. Incision and drainage of cutaneous abscess with or without cavity packing: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomised controlled trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg Epub. 2020 Aug 1. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-01941-9.

- O’Malley GF, Dominici P, Giraldo P, Aguilera E, Verma M, Lares C, Burger P, Williams E. Routine Packing of Simple Cutaneous Abscesses is Painful and Probably Unnecessary. Academic Emergency Medicine 2009; 16:470-473.

- Rencher L, Whitaker W, Schechter-Perkins E, Wilkinson M. Comparison of Minimally Invasive Loop Drainage and Standard Incision and Drainage of Cutaneous Abscesses in Children Presenting to a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2021; 37 (10): e615-e620. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001732.

- Singer AJ, Talan DA. Management of Skin Abscesses in the Era of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. New England Journal of Medicine. 370;11: 1039-1047.

- Singh, Indepreet. NEJM Abscess Incision and Drainage [video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwgNdrA18fM. Published September 30, 2013. Accessed January 9, 2023.

- Villareal, Logan, Kelsberg, Gary. What is the role of adding antibiotics to surgical incision and drainage for treatment of uncomplicated skin abscesses?. EVID BASED PRACT. 2022;25(5):18-19. doi:10.1097/EBP.0000000000001509.