Pyloric Stenosis

Objectives

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Recognize the presenting symptoms of pyloric stenosis.

- Know the classic metabolic derangements for infants with pyloric stenosis.

- Select the proper imaging study to diagnose pyloric stenosis.

Contributors

Update Authors: Saamia Masoom, MD; and Marideth Rus, MD.

Original Author: Marideth Rus, MD.

Update Editor: Adam McFarland, MD.

Last Updated: November 2024

Introduction

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) occurs when thickening of the pylorus muscle leads to gastric outlet obstruction in young infants, resulting in forceful vomiting after feeds. If left untreated, it may result in life-threatening dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities. HPS has an estimated prevalence of 17-50 per 10,000 infants, and is more common among males than females.2 While the cause is unknown, multiple potential genetic and environmental risk factors have been described. The risk factors for HPS include:

- Prematurity

- First-born children

- Young maternal age

- Maternal smoking2-3

Infants less than two weeks of age who have taken either azithromycin or erythromycin are also at increased risk for developing HPS.

A five-week-old male infant presents to the emergency department (ED) with vomiting. His symptoms started one week ago with occasional vomiting after feeds, but since then have gradually increased in frequency to the point where he now vomits after every feed. The parent describes the emesis as milk-colored, large in volume, and appearing to “shoot out” from the infant’s mouth. The infant was born at term after an uncomplicated pregnancy and has no other medical problems. He is exclusively breastfed and has had one wet diaper today. On exam, the infant is lethargic with dry lips and delayed capillary refill. An olive-shaped mass is palpable in his abdomen.

HPS most commonly presents between three and six weeks of age, but can present up to 12 weeks. There may be a history of failure to thrive or poor weight gain. Infants often present with forceful, “projectile” vomiting. Vomiting may initially occur only after some feeds, but then progressively worsens over a period of days until the infant begins to vomit after every feed. The emesis frequently looks like breast milk or formula. Infants continue to attempt to feed, and parents will generally report that the infant feeds vigorously but vomits shortly after. Peristaltic waves may sometimes be seen on exam, progressing from the left upper abdomen across to the right.

The classic finding on physical examination in infants presenting with HPS is a palpable “olive”-like mass in the stomach (not commonly seen). This is often accompanied by dehydration and can have significant electrolyte abnormalities, classically a hypokalemic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis caused by frequent vomiting. However, as patients with HPS are identified and diagnosed earlier, fewer have a palpable “olive”-like mass at diagnosis and the majority do not have the classic electrolyte derangements at presentation.1

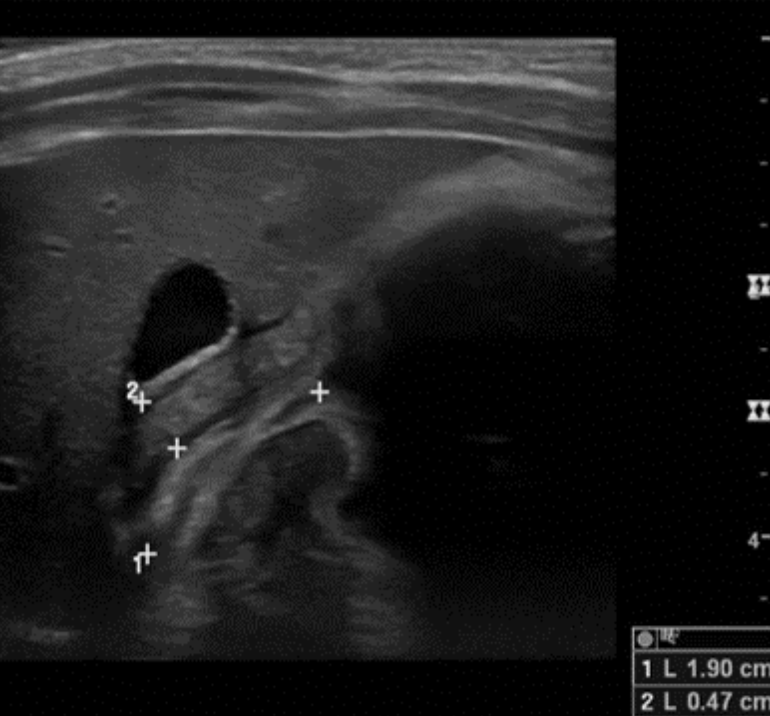

Diagnosis of HPS is most commonly made by ultrasound. An ultrasound is considered positive for HPS when the pylorus is visualized to have a thickness of greater than 3 mm and a length of greater than 14 mm - this may be recalled using the mnemonic of “pi” = 3.14. Infants with suspected HPS should also have serum electrolytes and bilirubin drawn to evaluate for possible metabolic derangements.

Figure: Ultrasound image demonstrating HPS. Image courtesy of Dr. Stephanie Leung. Used with permission.

Treatment of HPS is surgical with laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. Surgical consultation should be obtained once the diagnosis is made. However, the surgery is not emergent and the patient should be adequately hydrated and electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected prior to surgery. Initial fluid resuscitation should be with normal saline boluses, typically 20 ml/kg in healthy infants with normal cardiac function. Once the infant is well-hydrated and urinating, potassium chloride may be added to maintenance fluids if supplementation is indicated, or while volume losses (ie. vomiting) persist.

- Pyloric stenosis should be considered in infants three-six weeks of age presenting with progressively worsening "projectile" nonbilious emesis after feeds.

- The classic metabolic derangement in HPS is a hypokalemic, hypochloremic, metabolic alkalosis.

- When interpreting an ultrasound for HPS, remember "pi = 3.14." A pylorus visualized to be greater than 3 mm in thickness and 14 mm in length are consistent with HPS.

- Infants with HPS do NOT present with bilious emesis. In infants with bilious emesis, consider other causes of vomiting such as malrotation with volvulus.

The patient has an ultrasound in which the pylorus measures 4.7 mm in thickness and 19 mm in length. Serum chemistry is significant for potassium 2.7 mEq/L, chloride 92 mmol/L, and bicarbonate 31 mmol/L. Pediatric Surgery is consulted, and the patient is admitted to their service for laparoscopic pyloromyotomy following correction of electrolyte derangements with fluid resuscitation. Following the surgery, the patient is discharged as a happy baby who is tolerating feeds well.

- Glatstein M, Carbell G, et al. The Changing Clinical Presentation of Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis: The Experience of a Large, Tertiary Care Pediatric Hospital. Clin Pediatr. 2011.

- Kapoor R, Kancherla V, et al. Prevalence and Descriptive Epidemiology of Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in the United States: A Multistate, Population-Based Retrospective Study, 1999-2010. Birth Defects Res. 2019.

- Rich BS, Dolgin SE. Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis. Pediatr Rev. 2021.