Brain Imaging

Author Credentials

Author: Pratiksha Naik, MD, Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital, Temple, Texas

Editor: Lisa Bundy, MD, Magnolia Regional Health Center, Corinth, Miss.

Section Editor: Matthew Tews, DO, Indiana University School of Medicine

Update: 2023

Objectives

By the end of this module, the student should be able to:

- Understand basic anatomic landmarks.

- Learn a systematic way to read a head CT without contrast.

- Recognize emergent pathologies such as intracranial hemorrhage, stroke, tumor, fractures and more.

Introduction

Emergency physicians often encounter patients with head trauma, falls, altered mental status, severe headaches, and many other symptoms that lead us to order brain imaging. The most common being CT of the head without contrast. It is pertinent for emergency physicians to be able to rule out emergent pathologies by interpreting CT head imaging. In order to be able to easily read abnormal imaging, emergency physicians must be able to understand and identify normal basic anatomy. We can utilize the pneumonic “Blood Can Be Very Bad” to help systematically interpret a CT of the brain.

Basic Views

The most common views are the following:

- Axial

- Sagittal

- Coronal

Axial Sagittal Coronal

|  |  |

Figure 1. Imaging planes of the head. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Brain Anatomy and Key landmarks

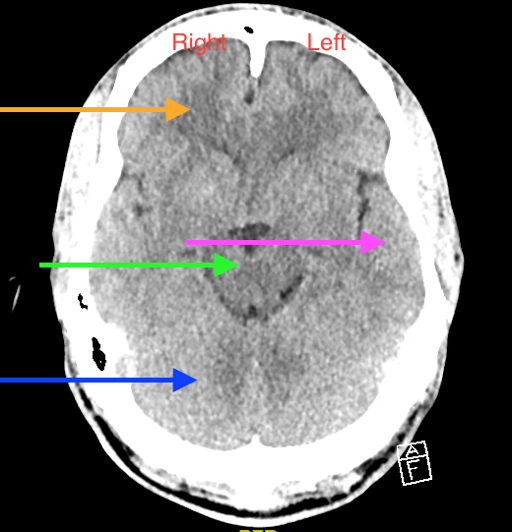

Now, let’s look at certain levels of the brain and identify key landmarks to help guide our reading. The right side of the brain will be on the left of your screen as marked in the below axial image and vice versa. The orange arrow in the below picture shows the right frontal lobe. The pink arrow shows the left temporal lobe; the green arrow shows the brainstem; the blue arrow shows the right cerebellum

Figure 2. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

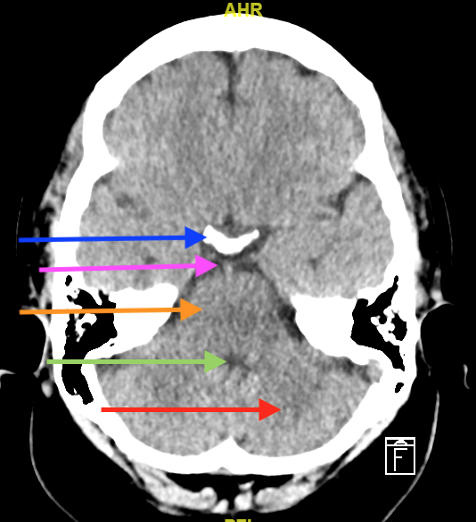

Figure 3. Image above: At the level of the high pons

Blue arrow:Dorsum sellae (where the pituitary gland sits)

Pink arrow: Suprasellar cistern

Orange arrow: Pons

Green arrow: Fourth ventricle

Red arrow: Cerebellum

Figure courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

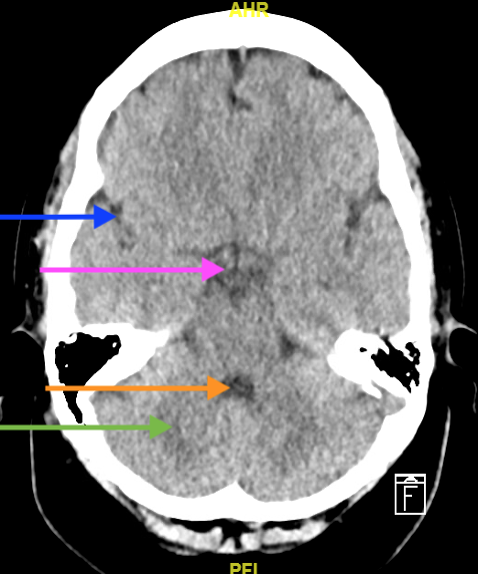

Figure 4. Image above: The level of cerebral peduncle

Blue arrow: Sylvian fissure

Pink arrow: Suprasellar cistern

Orange arrow: Fourth ventricle

Green arrow: Cerebellum

Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

|  |

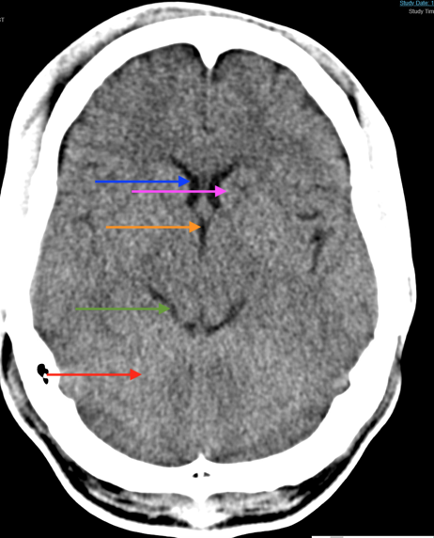

Figure 5. Image above: The level of high midbrain

Blue arrow: Lateral ventricle

Pink arrow: Internal capsule

Orange arrow: Third ventricle

Green arrow: Quadrigeminal cistern

Red Arrow: Top of cerebellum

Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

The Systematic Approach

Blood Can Be Very Bad

B: Blood

C: Cistern

B: Brain

V: Ventricles

B: Bones

Blood

Acute blood will be white on CT. There are five main types of bleeding on CT we should be able to easily identify. These are:

Epidural Hematoma

- biconvex in shape

- does cross midline, but typically not suture lines

- associated with tearing the middle meningeal artery

Subdural Hematoma

- lens shape

- does NOT cross midline

- associated with tearing of the bridging veins

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

- located within the parenchyma

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- aneurysms will account for 75% of SAH.

- the most common location is the Circle of Willis, therefore it is important to look in the suprasellar cistern.

- causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage include, but are not limited to, tumor, trauma, arteriovenous malformation, dural malformation and vasculitis.

The appearance of blood will differ depending on how long it has been there. It will be bright white initially, but changes isodensity at 1 to 2 weeks, and then appears hypodense at greater than 2 weeks. The highest sensitivity (98%) of identifying blood is 1 to 12 hours. The sensitivity drops to 90% at 24 hours.

Case 1: A 14-year old boy falls off the playground swing with LOC and vomiting. Upon presentation to the emergency department, the patient is awake and talking, but complaining of a severe headache. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 6. CT of the head for Case 1. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Epidural hematoma. There is a large mixed attenuation along right cerebral convexity with leftward midline shift.

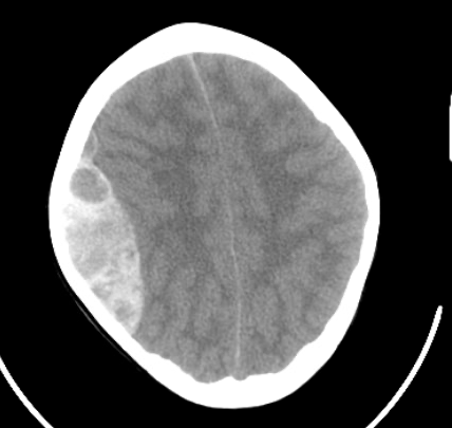

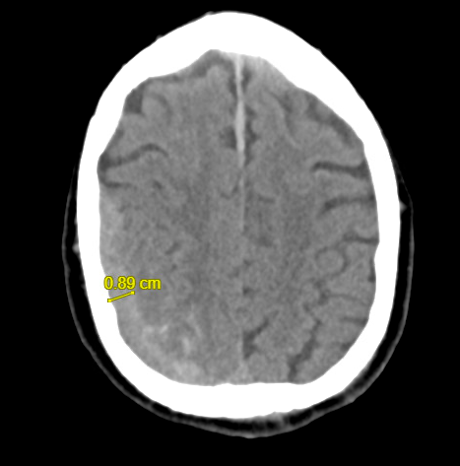

Case 2: An 86-year-old male presents with multiple falls over 3 days and progressive confusion. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

|  |

Figure 7. Case 2’s CT of the head. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Subdural hematoma. There is a bleed along the right cerebral hemisphere with associated mild midline shift. In addition, you will notice a small right subarachnoid hemorrhage in the image on the right.

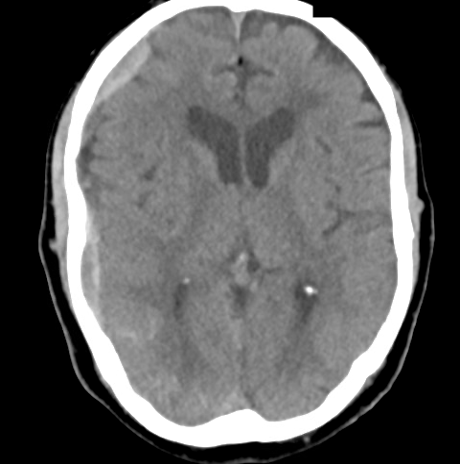

Case 3: A 59-year-old female on apixaban presents after sustaining a head injury. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 8. Case 3’s CT scan of the head. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Intraparenchymal hematoma with intraventricular extension

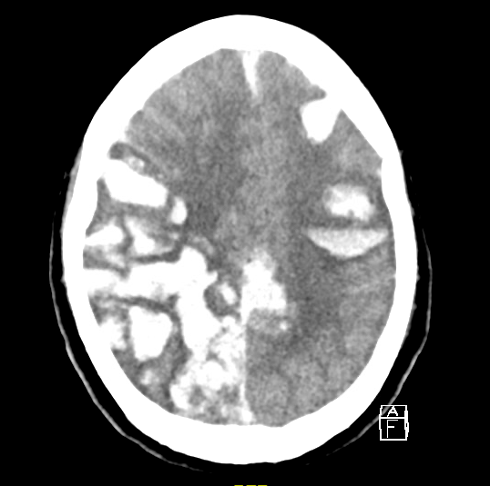

Case 4: A 67-year-old male presents in cardiac arrest via EMS. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 9. Case 4’s CT scan. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Multifocal hemorrhage.

Case 5: A 60-year-old male presents with severe onset 10/10 headache after lifting heavy weights. Ct shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 10. Case 5’s CT of the head. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Cisterns

Cisterns are cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) collections that surround the brain. It is anatomic space that is formed by openings in the subarachnoid space between the pia and arachnoid mater. When evaluating cisterns, you should look for blood in the cisterns and effacement. Blood would indicate subarachnoid bleed, and effacement means increased intracranial pressure. There are four main cisterns:

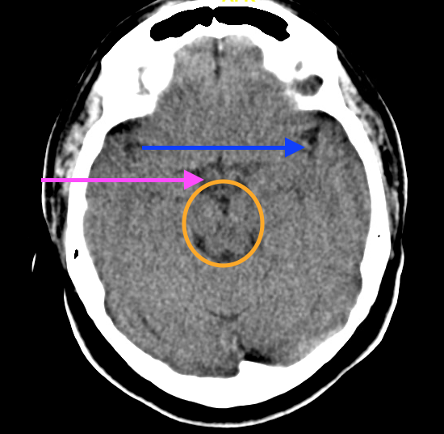

- Circummesencephalic (ring around midbrain): Orange circle in below image

- Suprasellar (star shaped/ Circle of Willis): Pink arrow in the image below on left. This is the area in front of midbrain, and an important area because it is the location of the Circle of Willis.

- Quadrigeminal: W shaped. Indicated by black arrow below.

- contains posterior arteries, superior cerebellar arteries, trochlear nerve, and posterior cerebral arteries.

- Sylvian: Between the frontal and temporal lobes. In the images below, it is the green arrow and blue arrow.

- scrutinize this fissure for distal MCA aneurysm and insular ribbon. The insular ribbon is the most distal part of the brain that is served by the MCA, which would show as loss of gray and white matter.

- it separates the temporal and parietal lobes.

|  |

Figure 11. The cisterns on a CT head. Image courtesy of Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas

Brain

The five aspects to evaluate when looking at the brain are:

- Symmetry: Ensure sulci and gyri appear the same on both sides.

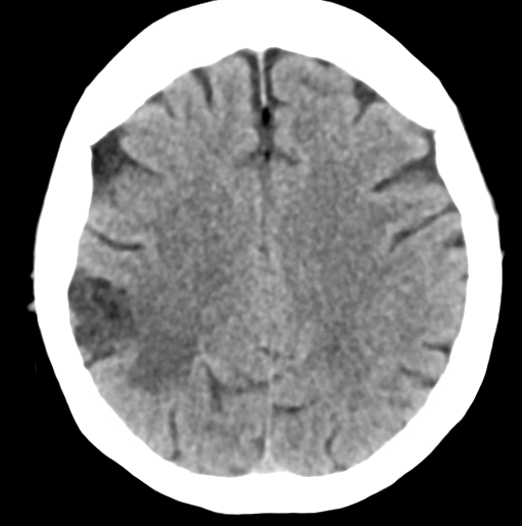

- Loss of gray/white differentiation: Earliest sign of CVA

- Shift: The falx should be midline with the ventricles on both sides.

- Hyperdensity and hypodensity: Blood, calcification, and IV contrast will show up hyperdense (lighter or white). Air, fat, ischemia, and the area around tumors (usually edema) are hypodense (darker).

- Pneumocephalus (air in the brain): This will appear black or almost black.

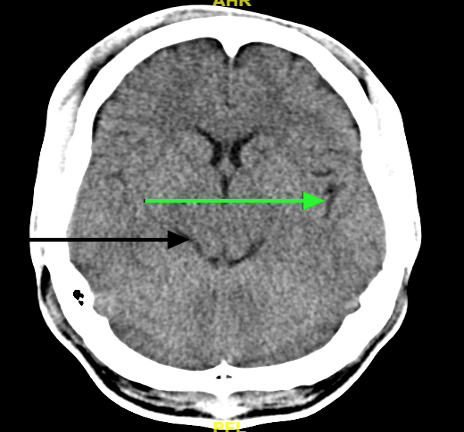

Figure 12. Notice asymmetry, loss of gray and white differentiation, and loss of insular ribbon on left. These features are commonly seen in early CVA. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Figure 13. Notice asymmetry, loss of gray/white differentiation, loss of the insular ribbon, and hypodensity in the posterior right MCA distribution. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

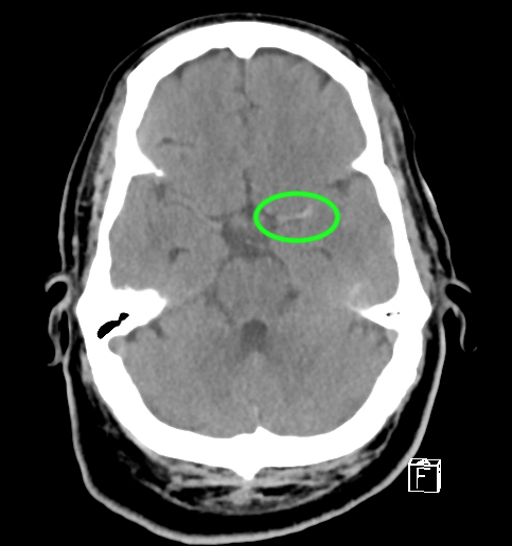

Figure 14. MCA sign. Please note the asymmetry, loss of gray and white differentiation, loss of insular ribbon, and a hyperdense MCA sign in the left middle cerebral artery, consistent with clot (green circle). Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas

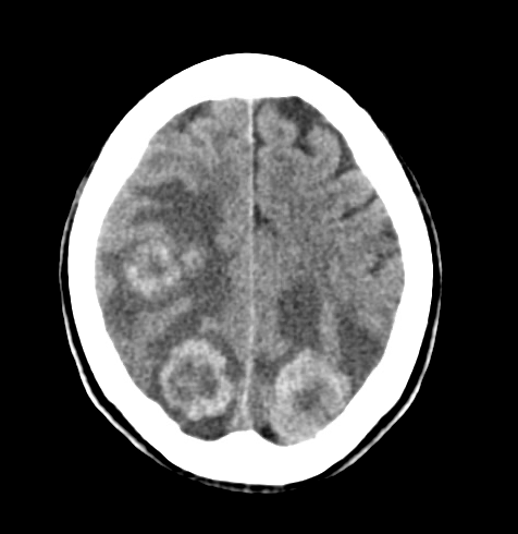

Figure 15. There are bilateral moderate-sized hemispheric hyperdense metastases involving the posterior parietal and occipital lobes. Notice the hypodense areas around the mets consistent with edema. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Figure 16. Pneumocephalus. It appears like dark bubbles in the brain. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas

Ventricles

Cerebrospinal fluid is produced in lateral ventricles, which then goes to the 3rd ventricle and into the aqueduct of Sylvius, and finally the foramina of Luschka. When evaluating ventricles, we should look for effacement, shift and blood.

Figure 17. Leftward midline shift complete effacement of right ventricle. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas

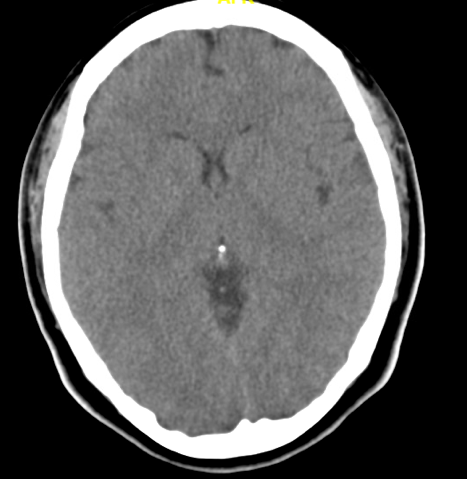

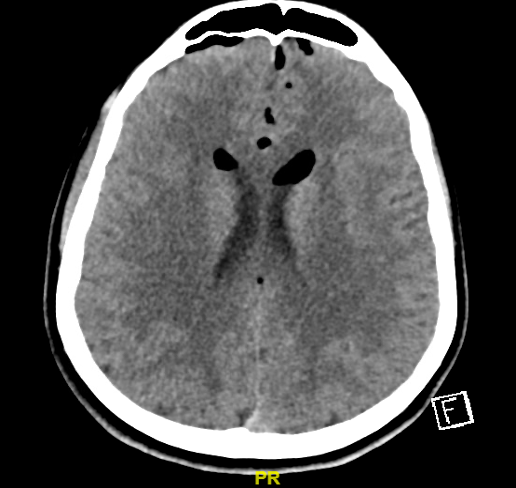

Case 6: A 12-year-old boy presents with nausea, vomiting, and headache for 1 month. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 18. Case 6’s CT of the head. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Hydrocephalus

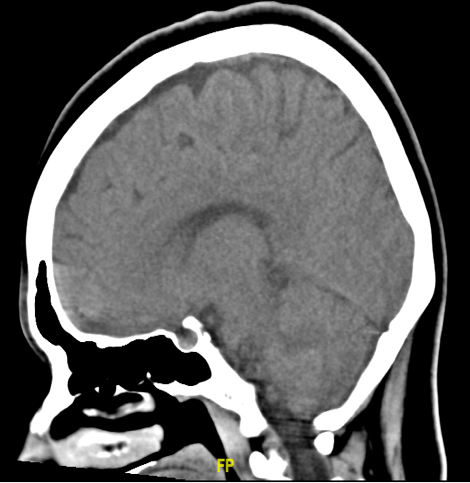

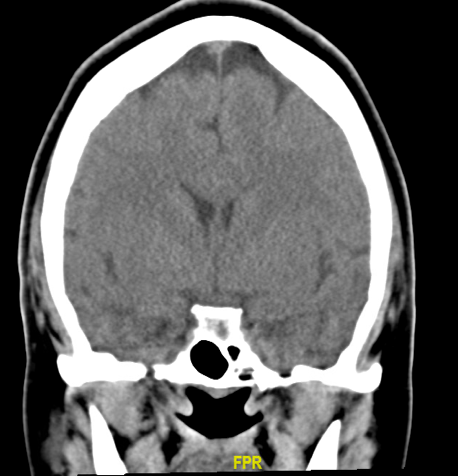

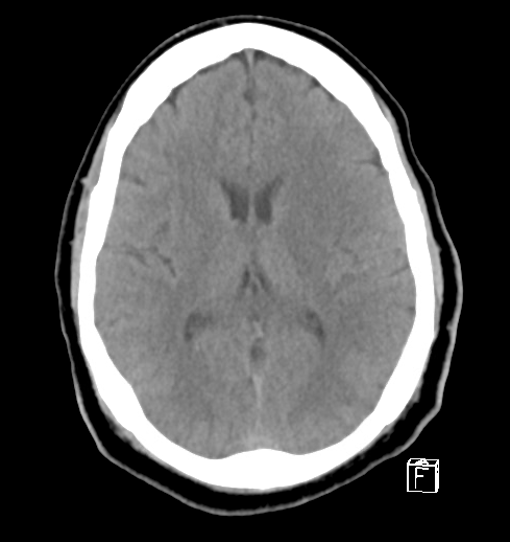

Case 7: An 89-year-old male presents with frequent falls, ataxia, and urinary incontinence. The CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 19. Case 7’s CT head. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

Bone

When evaluating bone, look for soft tissue swelling, blood in sinus/mastoid air cells, widened sutures, and fractures.

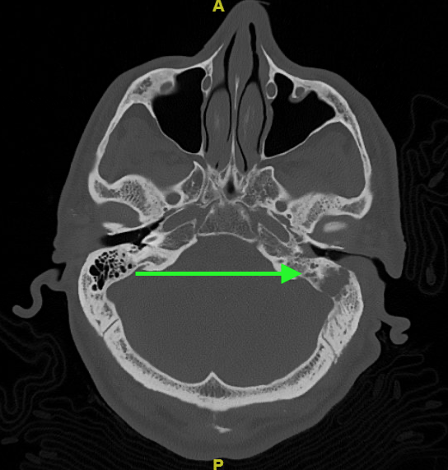

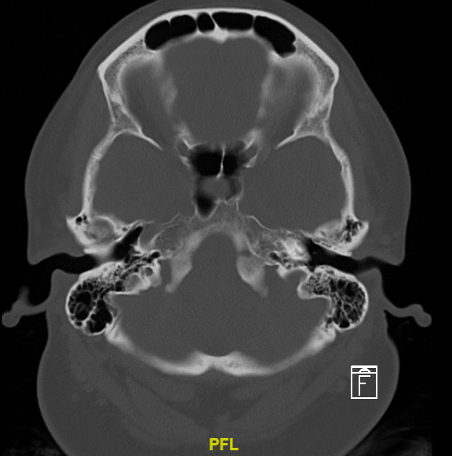

Case 8: A patient presents with fever and left ear pain, swelling and tenderness of the left mastoid. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 20. Case 8’s CT of the head. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Answer: Mastoiditis. Image shows left sided mastoiditis with opacification of the mastoid air cells (green arrow). Note the asymmetry of the mastoids, too.

The image below shows what normal air cells in the mastoid region look like.

Figure 21. Normal mastoid air cells. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas

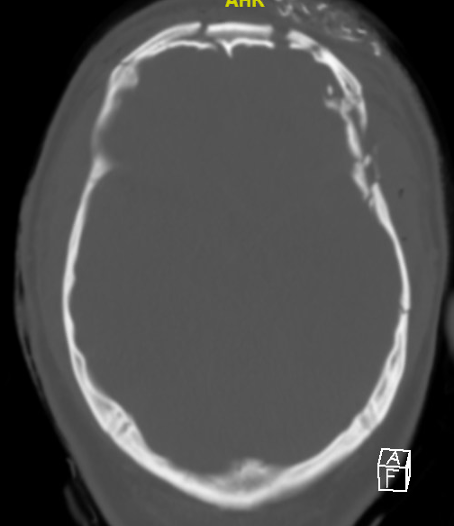

Case 9: This is a young male status post assault. CT shows the following. What is the diagnosis?

Figure 22. Case 9’s CT of the head showing multiple skull fractures including a depressed skull fracture. Image courtesy of the Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital–Temple, Texas.

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Be systematic when evaluating any radiologic study. Blood Can Be Very Bad is a systematic way to review CT imaging of the brain. If there is no blood, all cisterns are present/open, the brain is symmetric with normal gray/white differentiation, ventricles are symmetric without dilatation, and there is no fracture, then USUALLY there is no emergent diagnosis from the CT scan.

- Blood acutely will appear white on CT imaging. When blood collects over time or there are multiple episodes, then the collection will be hyperdense, isodense, or hypodense, depending on duration.

- When visualizing a CT, make sure you are utilizing the correct window to best view your area of interest. Use the brain window for looking for brain abnormalities, the bone window to look for skull fractures, etc.

- Normal areas that appear white on CT are bone, calcifications, and IV contrast.

References

- Soto, J. A., & Lucey, B. C. (2016). Emergency radiology: The requisites (2nd ed.). Elsevier - Health Sciences Division.

- How to read a head CT. (n.d.). NewYork-Presbyterian. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.nyp.org/professionals/emergency-medicine/how-to-read-emergency-images/how-to-read-a-head-ct

- Chapter vi-3. How to read a head CT in a patient with head trauma. Schwartz D.T.(Ed.), (2008). Emergency Radiology: Case Studies. McGraw Hill. https://accessemergencymedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=434§ionid=41825465

- All image credits to Baylor Scott and White Memorial Hospital, Temple, Texas