Cardiac Arrest

Objectives

- List the two most common causes of pediatric cardiac arrest

- Identify sick pediatric patients using the pediatric assessment tool (PAT)

- Describe pediatric CPR techniques and correct chest compression to ventilation ratios

- Describe indications and techniques for intraosseous (IO) cannulation

- Describe primary and secondary surveys

- List correct dosages of emergency resuscitation drugs

Introduction

Starting in the 1980s significant advancements have been made in pediatric resuscitation training. The American Heart Association offers courses in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). PALS prepares providers with knowledge and skills needed to effectively manage critically ill infants and children.

Unlike adult cardiac arrest, which is primarily caused by coronary artery disease, the most common causes of pediatric cardiac arrest are respiratory failure and shock. Timely recognition and management of these disease processes are essential goals of pediatric resuscitation.

Initial Actions and General Assessment

Back to Our Case – What’s your first step in managing this patient?

Obtain a quick general global assessment using the pediatric assessment tool (PAT). Important information can be gathered by the patient’s level of activity, muscle tone, and appearance. Often you are able to glean this information within seconds of entering the room.

- What is your patient’s general appearance? Ill with poor tone

- How would you describe your patient’s work of breathing? Grunting, indicating respiratory distress.

- What can you infer about your patient’s circulation? She was described as having mottled skin, which can result from poor end-organ perfusion and inadequate circulation.

Your systematic approach to pediatric assessment needs to be completed in conjunction with effective respiratory management.

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the child unresponsive with no breathing or only gasping?

- If yes, obtain airway equipment/defibrillator and simultaneously feel for a pulse

If the child is not breathing or gasping but has a pulse provide rescue breathing – 1 breath every 3-5 seconds, or about 12-20 breaths/min

If a pulse is absent or < 60 beats per min, begin CPR, attach monitor/defibrillator, obtain IV or IO access.

In children, carotid or femoral arteries are the most reliable methods to assess a pulse. In infants, brachial artery palpation is preferred. If no adequate pulse is detected within 10 seconds, CPR should be immediately initiated.

Chest compressions should be initiated at a rate of at least 100 per minute and at a depth of one-third of the anteroposterior diameter of the chest. They should be initiated before ventilation.

- For one rescuer CPR give 30 chest compressions alternating with two breaths

- Two-rescuer CPR should alternate between 15 chest compressions and two breaths

Effective chest compressions are critical. Make sure to allow for complete chest recoil and perform compressions over the lower sternum. While chest-compression-only CPR is an effective initial treatment for cardiac arrest in adults, infants and children should receive both chest compressions and ventilations.

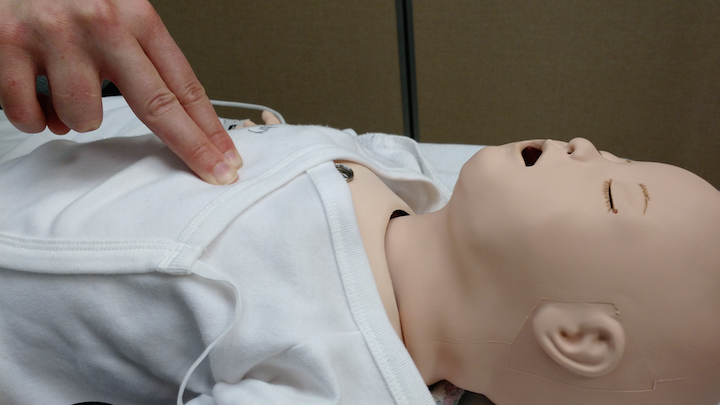

The preferred method for chest compressions in infants is to use both hands, encircling the chest with both thumbs, providing compressions on the lower sternum. The alternative technique is using two fingers from one hand to provide compressions.

Both of these techniques are shown below:

Venous access in children can be difficult. IO insertion is indicated if peripheral access cannot be obtained and emergent vascular access is needed. Most commonly the anterior/medial proximal tibia is used for cannulation. IO access provides a means of administering emergent medications, fluids, and obtaining blood. Traditional needles are inserted manually, but battery powered needle insertion devices are becoming more popular including use of the popular EZ-IO device.

To place an IO follow the directions below:

- Prep the site using aseptic technique. Aim for approximately 2 cm inferior to the tibial tuberosity

- Advance the IO needle though the skin until bone is contacted. Use the battery-powered drill handle to insert the needle

- Remove the trochar and confirm proper position by aspirating bone marrow

PALS algorithms are performed in conjunction with the primary and secondary surveys.

Primary Survey

- Airway – is the airway patent? Is the child crying, indicating a patent airway or is it obstructed?

- Breathing – is the child’s respiratory pattern normal, diminished or labored? Are there signs of breathing difficulties such as head bobbing or nasal flaring?

- Circulation – does the child have good pulses? Is the skin normal in appearance or pale, mottled, or cool?

- Disability – Assess level of consciousness using the AVPU system base on the following

- Alert (check to see if the child is alert)

- Voice (does the child respond to verbal stimuli)?

- Pain (does the child respond to painful stimuli)?

- Unresponsive (is the child unresponsive)?

- Exposure – undress the patient and look for signs of trauma, rashes, bleeding.

Secondary Survey

This includes a head to toe physical examination and brief history using the SAMPLE mnemonic

- Signs and symptoms of presenting complaint

- Allergies

- Medications

- Past medical history

- Last meal

- Events leading to current illness

The secondary survey for the 2 week old is outlined below:

- S – mom reports her daughter has had poor feeding over the past 12 hours

- A – no known allergies

- M – not on any medications

- P – she was born full term, mom was group B strep positive and does not recall being treated with antibiotics prior to delivery

- L – 6 hours ago was the last meal

- E – she was sleeping all day, not interested in eating, decreased urine output

Based on your global assessment this child is critically ill and needs immediate intervention. You call

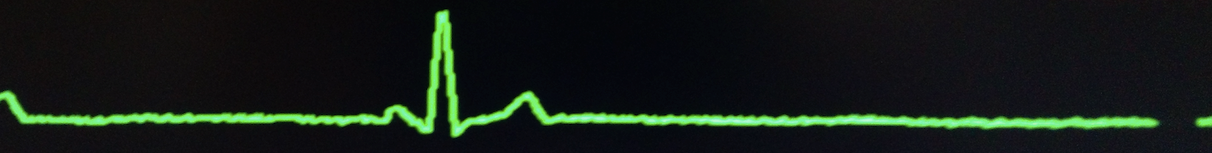

for help, immediately start high quality CPR, and put her on the cardiac monitor. You notice the following rhythm:

You recognize this as a brady-asystole pattern and in addition to high quality CPR and ventilatory support you recall the need for epinephrine.

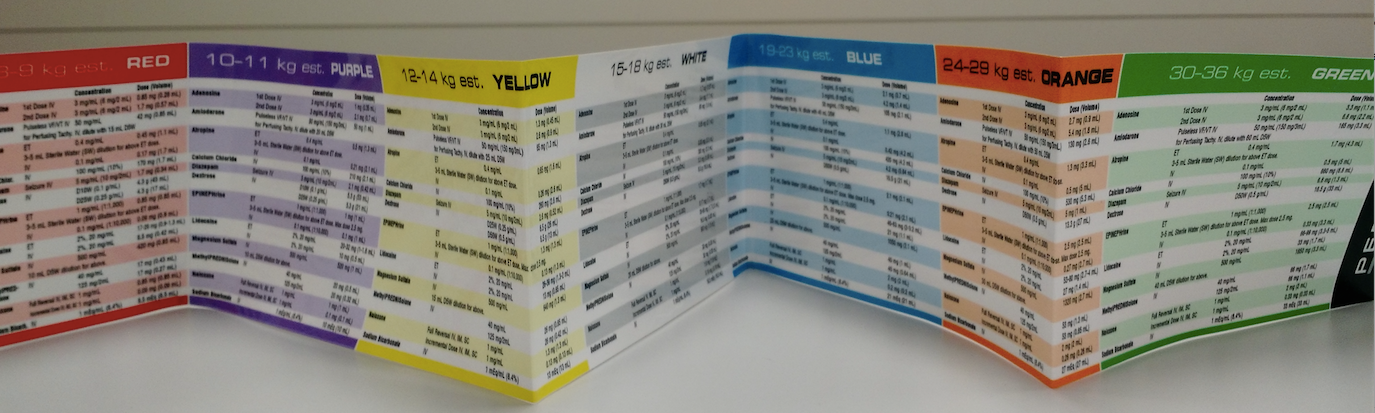

What is the correct dose of epinephrine? Administering the proper dosage of medications in pediatrics requires the patient’s weight. However, in emergency situations there is often not enough time to weigh the patient. PALS supports the use of the Broselow pediatric emergency tape to reduce errors involved in calculating correct dosages. The tape displays emergency resuscitation medication dosages based on a child’s length. It is easy and quick to use.

Below is a picture of the Broselow tape:

The dose of epinephrine is .01 mg/kg or 0.1 ml/kg of the 1:10,000 concentration given IV/IO, repeated every 3-5 minutes. If the initial dose is not effective, additional doses should be given at the same dose. High-dose epinephrine does not increase survival.

In situations where IV or IO access is not available, epinephrine 1:1,000 can be given via the endotracheal tube. The dose is 0.1mg/kg or 0.1ml/kg. A normal saline flush is instilled after the epinephrine.

After one round of epinephrine your patient regains pulses and you are able to secure a definitive airway.

Labs and Ancillary testing

While of limited value in the initial phases of cardiac resuscitation, the following labs may be useful later to help determine the etiology of the arrest: CBC, CMP, lactic acid, UA. Consider an arterial or venous blood gas to assess for acid/base status as well as a toxicology panel if clinical concern exists. Consider an ammonia level to look for any toxins or inborn errors of metabolism. A chest radiograph is useful to screen for congenital heart defects and to confirm correct endotracheal position.

Results

You consider a large differential diagnosis including: sepsis, severe metabolic derangements, toxins/drugs, inborn errors of metabolism, congenital heart disease, and non-accidental injuries.

Chest radiograph is without any cardiomegaly or vascular congestion to suggest a congenital heart disorder. Labs show low bicarbonate but otherwise no severe electrolyte abnormalities. Urine analysis showed no evidence of infection. Toxicology panel is normal. No clinical or historical evidence to suggest traumatic injury. You remember neonates are prone to serious bacterial infections. This patient’s mother tested positive for group B strep but never received proper prophylactic antibiotic treatment. With a high suspicion for sepsis you initiate fluid resuscitation, and start broad spectrum antibiotics. You also successfully perform a lumbar puncture, obtain blood cultures, and admit the patient to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Final diagnosis: Septic shock which ultimately led to respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse.

Case Pearls

- Cardiac arrest in the pediatric population is most often secondary to respiratory arrest and shock. Recognizing ill children early and intervening quickly improves outcomes.

- Venous access can be difficult in pediatrics and attempts at vascular access should not interrupt chest compressions or ventilatory support

- Pediatric patients should receive both chest compressions and ventilatory support rather than chest compression-only CPR

- Weight based resuscitation tapes can be a valuable resource in critically ill infants and children

References

- American Heart Association. Web-based Integrated Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary and Emergency Cardiovascular Care – Part 12. Pediatric advanced life support. https://eccguidelines.heart.org/index.php/circulation/cpr-ecc-guidelines-2/part-12-pediatric-advanced-life-support/ (Accessed on December 15, 2015).

- López-Herce J, García C, Domínguez P, et al. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2005; 21:807.

- de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, et al. Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2015; 132:S526

- Schindler MB, Bohn D, Cox PN, et al. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac or respiratory arrest in children. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:1473.

- Young KD, Seidel JS. Pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a collective review. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 33:195.

Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support Techniques

Authors: Shannon MacRitchie, DO, EM Resident, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Daniel Mielnicki, MD, Assistant Professor of EM, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Editor: S. Margaret Paik, MD, FAAP FACEP , The University of Chicago