Neck Trauma

Author Credentials

Author: Nicholas E. Kman, MD OSU Wexner Medical Center Department of Emergency Medicine

Editor: Nur-Ain Nadir. MD, Kaiser Permanente Central Valley Modesto & Chris Fowler, DO, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Last Updated: November 2019

Case Study

You are working in the Emergency Department when you take an EMS report. The EMS provider sounds anxious on the phone and states, “We are 4 minutes out with a gun shot wound to the neck. The patient has gurgling, spontaneous respirations and there are bubbles coming out of his anterior neck wounds. His blood pressure is 80/40 and O2 sat is 88%. See you soon!”

As you walk to the trauma bay, you start going over in your head the management of neck trauma and preparing your airway equipment…

Objectives:

Upon finishing this module, the student will be able to:

- Describe the approach to blunt neck trauma

- Describe the approach to penetrating neck trauma

- Describe the approach to Cervical Spine Trauma

- Review Principles of ATLS as they pertain to neck trauma.

- Define the role of diagnostic tests in assessing neck trauma

Introduction

Neck trauma poses a challenge to emergency providers secondary to the large amount vital structures that occupy a very small amount of real estate. The airway, vascular system, neurological system, and gastrointestinal tract are all found in this small area and can all be involved in a seemingly innocuous injury. Additionally, spinal injuries must always be considered in patients with multiple injuries, either blunt or penetrating.

Acute laryngeal trauma is a rare and potentially lethal injury. It is classified as either blunt or penetrating, according to the mechanism of injury. Blunt trauma is more common than penetrating trauma. Motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) are the most common cause of blunt laryngeal trauma and these often occurs in the setting of multi-system trauma. Gunshot or stab injuries are the most common cause of penetrating laryngeal trauma.

Handling patients with neck trauma is of great importance. Excessive manipulation and inadequate immobilization of neck injured patients may cause additional neurologic damage and worsen the patient’s outcome. According to ATLS, at least 5% of patients with spine injury experience the onset of neurologic symptoms or the worsening of preexisting symptoms after reaching the ED. This chapter will describe neck injuries as they relate to the injured patient.

Initial Actions and Primary Survey

Assessing a patient for neck trauma begins with the primary survey. As with all of your patients, your assessment should always begin with addressing airway, breathing and circulation. Each problem is addressed prior to moving to the next priority (ie, manage airway prior to treating hemorrhage). Notice that addressing the cervical spine occurs immediately with A (airway) and is also assessed with the neurologic exam that is done as a part of D (disability) and the secondary survey

A: Airway Maintenance with CERVICAL SPINE protection- Securing an airway is especially important in suspected laryngotracheal injury. That said, attempts to align the spine for the purpose of immobilization on the backboard are not recommended if they cause pain.

B: Breathing and Ventilation

C: Circulation with hemorrhage control / shock assessment. Bleeding should be controlled with pressure rather than blind clamping.

D: Disability: Neurological status

E: Exposure/Environmental control

Presentation

This section will describe the classic “textbook” presentations with relevant history and physical. When we can, we will comment on the sensitivity or specificity of any findings. We will also make note of any features that can be used to rule-in (pathognomonic) or rule-out the disease process, if such exist. We will also note any variations on the normal presentation.

Cervical Spine and Neck Injury Overview

Neck trauma is usually divided into two categories, blunt and penetrating trauma.

- Blunt Trauma-may result in crushed larynx, tracheal disruption, expanding hematoma, esophageal leak.

- Penetrating trauma-may result in injury to major vascular structures, pharynx, larynx, trachea, esophagus

Physical Exam may be misleading as neck trauma may show subtle symptoms and signs prior to airway obstruction or physiologic decompensation. Some pearls follow below

Obstruction secondary to trauma may be due to direct trauma to larynx or neck or from an expanding hematoma/swelling from a nearby structure

Document the patient’s history and physical examination so as to establish a baseline for any changes in the patient’s neurologic status. [4, 10]

Physical exam findings that suggests a compromise of the airway include:

- inspiratory stridor (supraglottic)

- stridor (subglottic)

- muffled voice

- difficulty handling secretions.

Wounds that violate the platysma need to be evaluated further to rule out injury to underlying injury. Blindly probing is contraindicated as it may dislodge a clot and cause massive hemorrhage.

Quick assessment of neurologic status done as part of primary survey in “Disability”.

Cervical Spine Injuries:

The spinal column consists of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae. There are 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, and 5 lumbar vertebrae, as well as the sacrum and the coccyx. The spinal cord contains three important tracts: the corticospinal tract, the spinothalamic tract, and the dorsal columns, and injuries to these tracts can cause neurologic deficits.

Some important facts about cervical spine fractures include:

- 55% of spinal injuries are cervical. The cervical spine is the most vulnerable to injury because of its mobility and exposure.

- 10% of patients with C-spine fractures will have a second noncontiguous vertebral fracture

- 5% of brain injuries have an associated C-spine injury.

Now on to some definitions. A complete spinal cord injury is complete loss of motor and sensation below the level of injury, and an incomplete spinal cord injury still retains some level of function below the level of injury.

Spinal cord injury may be categorized by severity as follows:

- Incomplete paraplegia (incomplete thoracic injury)

- Complete paraplegia (complete thoracic injury)

- Incomplete quadriplegia (incomplete cervical injury)

- Complete quadriplegia (complete cervical injury)

Patients with a spinal cord injury can present with both motor and neurologic deficits. The paralysis is a flaccid paralysis in the acute setting. There are also some classic spinal cord injury patterns that clinicians should be familiar with as these patients may have a normal CT of the spine.

- Central Cord Syndrome

- Mechanism- extension injury

- Affects motor more than sensory

- Affects upper extremities more than lower extremities

- Affects distal extremity more than proximal

- Anterior Cord Syndrome

- Mechanism: Flexion injury

- Preserved proprioception and vibration sense intact below level of injury

- Loss of motor function, sense of light touch, pain and temperature below the level of injury

- Brown-Sequard Syndrome (hemi-cord injury)

- Mechanism: Classically penetrating trauma

- Ipsilateral loss of motor function, and the ability to sense vibration and proprioception

- Controlateral loss of motor and temperature

Another complication associated with spinal cord injury is neurogenic shock. This is a distributive shock which is thought to be caused by the acute loss of sympathetic tone due to spinal cord injury, classically above T5. This can cause hypotension and a relative bradycardia.

Cervical spine and spinal cord injuries should be suspected in any patient with neck pain and/or neurologic deficits. Fortunately, a couple of clinical decision rules have been developed to help clinicians figure out if a patient requires cervical spine imaging. A popular rules is the NEXUS criteria for C-Spine imaging.

NEXUS Criteria for C –Spine imaging

- Patient requires imaging if any of the following is present:

- Focal neurologic deficit

- Midline C-spine tenderness to palpation

- Altered level of consciousness

- Patient is intoxicated

- Distracting injury is present

Penetrating Neck Trauma Presentation:

Penetrating trauma has a high rate of serious injury given the large amount of vital structures enclosed in a small amount of area. Any penetrating injury that violates the platysma is at high risk for injury to underlying tissue and necessitates further evaluation.

Before going forward to the different presentations, the Emergency Medicine clinician must be familiar with hard and soft signs on physical exam that the patient has a serious injury. In particular, it is important to note that patients with any of the hard signs should be taken expeditiously to the operating room for definitive management.

- Hard Signs

- Airway compromise

- Expanding or pulsatile hematoma

- Active, brisk bleeding

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Hematemesis

- Neurologic deficit

- Massive subcutaneous emphysema

- Air bubbling through wound

- Soft Signs

- Hemoptysis

- Oropharyngeal blood

- Dyspnea

- Dysphagia

- Dysphonia

- Nonexpanding hematoma

- Chest tube air-leak

- Subcutaneous or mediastinal air

- Vascular bruit or thrill

- Crepitus

Classically, penetrating trauma has been broken up into three zones to help clinicians decide the next diagnostic and therapeutic steps.

The three zones and their diagnostic management are:

- Zone III-

- Anatomy: Above angle of mandible.

- Diagnosis: Angiography

- Zone II-

- Anatomay: Angle of mandible to the cricoid.

- Diagnosis: Explore, observe, consider dopper and CTA

- Zone I-

- Anatomy: below cricoid cartilage

- Diagnosis: Angiography, highest mortality, EGD, esophagoscop

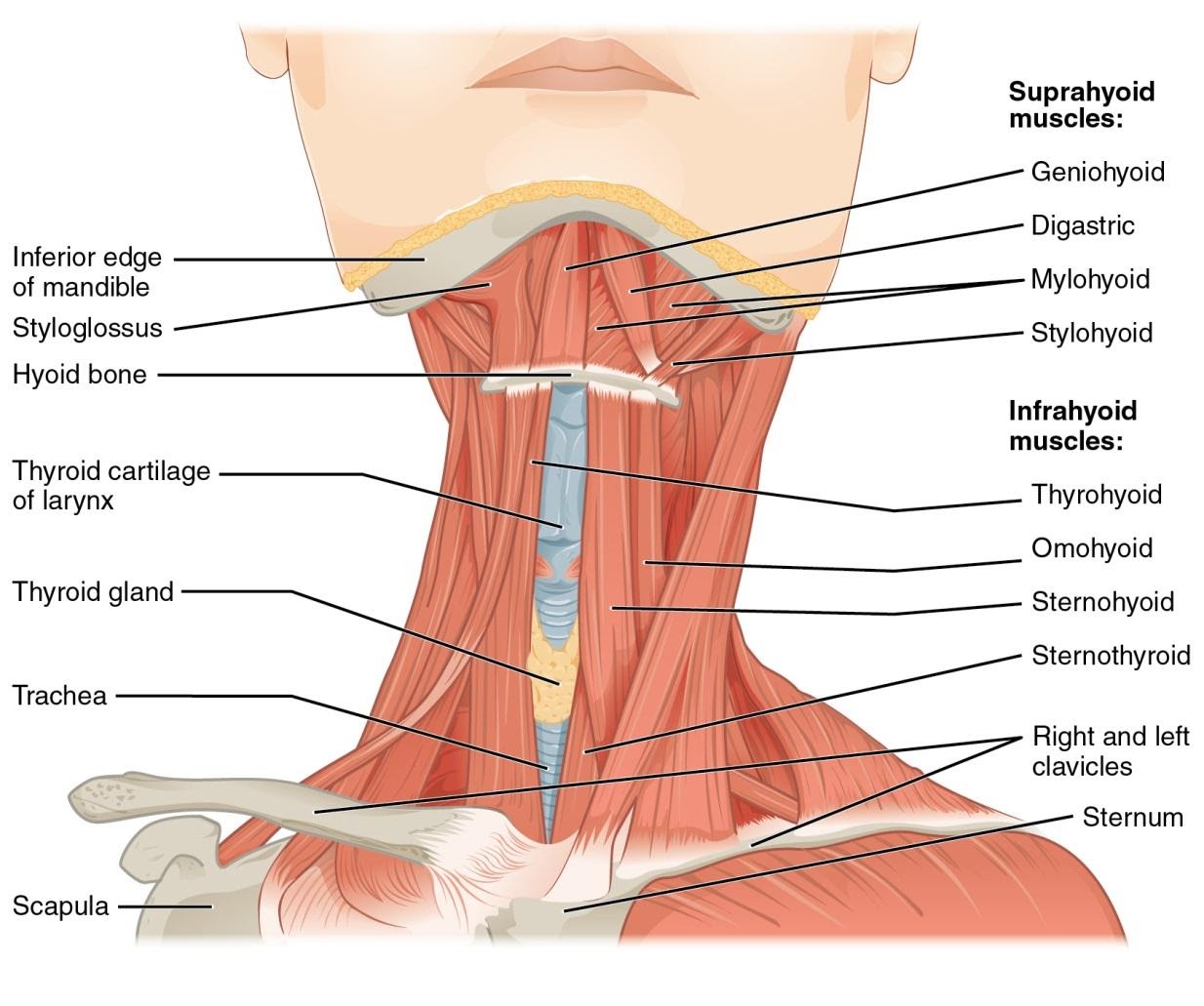

Figure 1. Anatomy of the neck. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1110_Muscle_of_the_Anterior_Neck.jpg

It is important to note that some trauma centers have moved away from using the “zones” in penetrating neck trauma, and have instead used a zone free or “no-zone” approach with using CTA of the neck as first line diagnostic imaging. Please use the practice that is standard at your trauma center. The following is from a recent UptoDate article. “The no-zone approach is relatively new and evidence about its effectiveness is limited. One potential problem is the limitations of MDCT-A for detecting pharyngoesophageal injuries, which are potentially life-threatening if missed. Given the controversies about the management of PNI [penetrating neck injury], limited evidence base, and variability in resources and experience, decisions about whether to use a selective, zone-based management approach or a no-zone approach will vary by local expertise and resources and are likely to remain institution-specific for the time being.” 12

On physical exam, it is important not to blindly probe any wounds in the neck because you may dislodge a clot that was preventing a major hemorrhage, provoking exsanguination.

Blunt Neck Trauma Presentation:

History

As with all traumatic injuries a full and accurate history is going to aid in determining further diagnostic test and will direct management. Practitioners should ask about the mechanism of the accident, use of restraint or airbag deployment, and associated injuries. Blunt neck trauma can result in laryngeal trauma, such as tears and possibly crush injury and are frequently associated with MVCs. Penetrating injury related to GSW or stab wounds are going to inflict a different pattern of injury. Assaults, sports related injuries and clothesline-type injuries are also common

Children can also present with neck injury, less likely to be penetrating. These mechanisms can occur during MVCs but bicycle accidents, clothesline injuries and injury sustained during falls are common.

Hanging is another mechanism of injury in neck trauma. Ligature suffocation, choking, and excessive manipulation of the cervical spine in a distracted manner are common among hanging patients. During a hanging there is increased pressure on jugular veins which prevents venous return from brain resulting in LOC. Unconscious patient falls with weight against ligature, compressing trachea and restricting airflow to lungs and asphyxiation follows. If there is sufficient force during a hanging there can be spinal cord compromise.

Physical

A detailed physical exam is necessary in neck trauma patients. Because the intricate nature of the anatomy of the neck, numerous vital structures can be disrupted. Internal anatomy can be difficult to assess.

Looking for the following is crucial:

- Inspiratory stridor (supraglottic) or expiratory stridor (subglottic)

- Muffled voice

- Difficulty handling secretions or hemoptysis

- Ecchymosis

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Absent thyroid prominence

- Neck or facial crepitus

- Cartilaginous step off

- Expanding hematoma

Early findings may be subtle and frequent re-evaluation is necessary. Examination of neck wounds should be approached carefully. Violation of the platysma muscle should lead to further evaluation. Probing of the wound may be dangerous, because a vascular structure that has ceased to bleed may resume.

Diagnostic Testing

This section will make special note of any testing which can be used to rule-in or rule-out the disease process. We will include any clinical scoring systems that are applicable as well.

- Lab Tests:

- May consider obtaining a trauma panel including CBC, chemistry panel, PT/INR, type and screen and VBG/ABG in the setting of significant injury, but are not diagnostic of laryngotracheal trauma

- Neck Trauma Diagnostic Measures:

- Larynx – CT is gold standard. CT angiography may be incorporated if vascular injury suspected.

- Laryngoscopy should be considered with changes in phonation

- Fiberoptic laryngoscopy is an excellent way to evaluate the supraglottic and glottic larynx; it has limitations in evaluating the subglottic area. Examination is best performed with the patient in the upright position to prevent obscuring of the anatomy by the tongue base. [3]

- Remember that patients initially presenting with a stable-appearing airway may progress to airway obstruction secondary to swelling. Unstable patients or patients with impending airway obstruction should not be sent to the CT scanner [3]

- Cervical spine- CT of the c- spine is standard of care for assessing the cervical spine, it is more sensitive and specific that c-spine xrays.. Clinical decision rules have been developed to see whether patients with neck trauma need neck imaging. The most commonly used rule is the NEXUS criteria for C- Spine imaging[4] The NEXUS criteria follow below:

- Patient requires imaging of the cervical spine if any of the following is present:

- Focal neurologic deficit

- Midline C-spine tenderness to palpation

- Altered level of consciousness

- Patient is intoxicated

- Distracting injury is present

- Esophagus – endoscopy can be used to evaluate for esophageal injury.

- Vascular Injury-Angiography if active bleed or pulse deficit; blood in the GI tract, hoarseness, subcutaneous air, or respiratory distress

- Surgical exploration is also a diagnostic option for laryngeal, esophageal and vascular injuries.

Prehospital Treatment

- Prehospital care should focus on maintaining an airway.

- Definite airway only when necessary.

- Partial airway injuries may lead to complete obstruction during intubation.

- Hemorrhage controlled with direct pressure only.

- Spine immobilization secondary to airway maintenance and control of bleeding in patients who are neurologically intact.

- Massive hemorrhage from a cervical vascular injury may kill more quickly than a suboptial airway (MARCH).

- Cervical Spine Immobilization in low velocity, penetrating neck trauma may not be necessary and may be detrimental [11].

ED Treatment

- General measures: ABCs- Perform primary survey (ABCDEs) and identify and address all life-threats [4]

- Securing an airway is essential in suspected laryngotracheal injury

- Cervical spine must be secured and immobilized

- The rest of the treatment is based on the location of injury or zone*. If the patient is stable, awake flexible fiberoptic examination can be performed; if minimal trauma visualized, oral intubation can be attempted

- If attempts at oral intubation fail or are unsafe due to significant trauma, a surgical airway is required. Formal tracheotomy is preferred over cricothyrotomy but if patient is unstable, a cricothyrotomy should be attempted [2,3]

- Laryngeal mask airways (LMA) are contraindicated, as they can occlude the airway and may also ventilate air through mucosal defects in the larynx to the neck. [3]

- Control bleeding with direct pressure- if platysma is violated do not probe

- Using a foley has been described to tamponade bleeding from neck wounds

- Perform secondary survey (head to toe exam) with a focused neck examination

- Foreign bodies should be removed in the operating room

- Early consultation is imperative. If surgery is required, the goal should be to conserve all viable structures [5]

- Uncontrolled hemorrhage, shock not responding to resuscitation, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, airway compression, and airway communication with wound (as evidenced by bubbling) are all indications for immediate surgical intervention.

- Surgical methods vary based on the type of injury. In one review of pediatric patients, Tracheotomy (16 procedures), laryngeal suturing (13 procedures), and laryngeal fracture repair (10 procedures) were the most frequent procedures identified. [6]

* The no-zone approach is relatively new and evidence about its effectiveness is limited. It is important to note the limitation of CTA for detecting pharyngoesophageal injuries, which are potentially life-threatening if missed. Given the controversy about the management of the zones in penetrating neck trauma, limited evidence base, and variability in resources and experience, decisions about whether to use a selective, zone-based management approach or a no-zone approach will vary by local expertise and resources and are likely to remain institution-dependent.

Cervical Spine Treatment

Attend to life-threatening injuries first, minimizing movement of the spinal column. Establish and maintain proper immobilization of the patient until vertebral fractures and spinal cord injuries have been excluded. Obtain early consultation with a neurosurgeon and/or orthopedic surgeon whenever a spinal injury is detected. [4]

At present, there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of steroids in spinal cord injury. [4]

Esophageal Injury Treatment

- Delay in diagnosis and repair of esophageal injuries associated with increased mortality because of mediastinitis.

- Surgery is performed less than 24 hours after injury, survival rate >90%.

- Surgery is performed >24 hours after injury, it is just 65%.

- Delay in diagnosis and repair of esophageal injuries associated with increased mortality because of mediastinitis.

- Surgery is performed less than 24 hours after injury, survival rate >90%.

- Surgery is performed >24 hours after injury, it is just 65%. [11]

Neurogenic Shock Treatment

The patient with neurogenic shock will be hypotensive because of massive vasodilation and a relative bradycardia due to loss of sympathetic tone. Treatment will include aggressive fluid hydration to fill the new enlarged vascular space and vasopressors as needed. Dopamine, phenylephrine and norepinephrine have all been successfully used in the treatment of neurogenic shock.

Disposition

- All patients with known injury to the laryngotracheal complex should be admitted for observation for at least 24–48 h with serial examination. [3]

- Cervical spine injury requires continuous immobilization of the entire patient with a semi-rigid cervical collar, head immobilization, backboard, tape, and straps before and during transfer to a definitive-care facility. [4]

Prognosis

- 78% of patients who received early treatment had good voice outcomes [2]

- Nearly 90% of all patients had a good result for deglutition.

- Expedient evaluation, treatment and management often result in favorable outcomes especially with blunt laryngeal trauma

Pearls and Pitfalls

- A high index of suspicion is need to detect subtle laryngotracheal injuries, especially in the multi-system trauma patient

- Airway management may be difficult

- Early detection and treatment leads to good outcomes

- Cervical spine injuries above C6 can result in partial or total loss of respiratory function.

- Pitfalls [4]:

- An inadequate secondary assessment may result in the failure to recognize a spinal cord injury.

- Patients with a diminished level of consciousness or intoxication are often difficult to assess for the presence of spinal cord injury. These patients require repeat assessment once initial life-threatening injuries have been managed.

- Patients being transported to a trauma center may have unrecognized spinal injuries and should be maintained in complete spinal immobilization.

Case Study Resolution

The patient arrives to the Emergency Department in frank respiratory distress with gurgling respirations and bubbles coming out of the anterior neck wounds. The patient is emergently intubated and the team notes the multiple hard signs in this patient with penetrating neck trauma. The trauma surgeon is at bedside and takes the patient expeditiously to the operating room. You walk to the family waiting room to discuss the patient’s condition with his family while thanking your lucky stars that this difficult intubation did not go south…

Figures

Figure 2: Self-inflicted knife laceration to neck. Patient intubated orotracheally to protect airway. Used with permission from Dr. Colin Kaide, Ohio State University Department of Emergency Medicine.

Figure 3: Shotgun pellet wounds diffusely to head and neck. Patient had penetrating neck wound causing laryngeal injury and airway compromise. Used with permission from Dr. Howard Werman, Ohio State University Department of Emergency Medicine.

Figure 4: Gunshot wound to the neck with hematoma causing airway compromise. Patient intubated for airway protection. Used with permission from Dr. Colin Kaide, Ohio State University Department of Emergency Medicine.

References

A short list of important articles with the PubMed links / ID.

- Lee, WT.; Eliashar, R.; Eliachar, I. “Acute external laryngotracheal trauma: diagnosis and management.” ENT: Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, v. 85 issue 3, 2006, p. 179-84.

- Butler, AP.; Wood, BP.; O’Rourke, AK.; Porubsky, ES. “Acute external laryngeal trauma: experience with 112 patients.” Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, v. 114 issue 5, 2005, p. 361-8.

- Comer, BT.; Gal, TJ. “Recognition and management of the spectrum of acute laryngeal trauma.” Journal of Emergency Medicine, v. 43 issue 5, 2012, p. e289-93.

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. ATLS: 9th edition. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- Smith, DF., et al. “Complete traumatic laryngotracheal disruption–a case report and review.” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, v. 73 issue 12, 2009, p. 1817-20.

- Sidell, D.; Mendelsohn, AH.; Shapiro, NL.; St John, M. “Management and outcomes of laryngeal injuries in the pediatric population.” Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology, v. 120 issue 12, 2011, p. 787-95.

- Heidegger, T. “Videos in clinical medicine. Fiber optic intubation.” New England journal of medicine, v. 364 issue 20, 2011, p. e42.

- Hsiao, J.; Pacheco-Fowler, V. “Videos in clinical medicine. Cricothyroidotomy.” New England journal of medicine, v. 358 issue 22, 2008, p. e25

- Gray, H. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1918.

- Ibraheem K, Khan M, Rhee P, Azim A, O'Keeffe T, Tang A, Kulvatunyou N, Joseph B. "No zone" approach in penetrating neck trauma reduces unnecessary computed tomography angiography and negative explorations. J Surg Res. 2018 Jan;221:113-120. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.08.033. Epub 2017 Sep 18. PubMed PMID: 29229116.

- Burgess, C A (02/2012). "An evidence based review of the assessment and management of penetrating neck trauma". Clinical otolaryngology(1749-4478), 37(1), p. 44.

- Newton, K, Moreira M, Bachur R, “Penetrating neck injuries: Initial evaluation and management” UpToDate Jan 2020 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/penetrating-neck-injuries-initial-evaluation-and-management?search=pentrating%20neck%20injury&source=search_result&selectedTitle=3~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=3#H810134564