The consultation process

Author Credentials

Author: Andrew Golden, MS4, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

Author: Keme Carter, MD, University of Chicago

Editor: Matthew Tews, DO, MS, Medical College of Wisconsin

Last Update: 2016

Introduction

Communication breakdowns are common sources of medical errors. In fact, as high as 70% of medical errors have been attributed to failures in effective communication. Communication happens in various forms throughout the emergency department; one common type is the consultation, or one provider seeking formal recommendations from another provider regarding the care of a patient. Forty percent of all ED visits require at least one consultation by emergency medicine providers.

In the emergency department, four types of consultations have been described:

- “Immediate critical interventions” include consultations to physicians for management of an emergency outside of the scope of practice of an emergency medicine physician. An example of this includes consulting an interventional cardiologist for potential reperfusion therapy in a patient with a STEMI.

- Procedural interventions include consultations for procedures outside of the scope of practice of an emergency medicine physician. An example of this includes consulting orthopedic surgeons for a complicated fracture reduction.

- “In-person evaluation and management inquiry” includes consultations for diagnosis or management of a patient. An example of this includes consulting an endocrinologist for evaluation and management of a patient with a new diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

- “Remote evaluation and management inquiry,” or telemedicine, includes consultations for diagnosis or management of a patient, although not through an in-person encounter. An example of this includes rural emergency medicine physicians consulting with neurosurgical subspecialists at a tertiary care hospital regarding surgical management of a patient’s subdural hematoma.

Curbside consultations, or unstructured consultations, whereby a consultant is asked to provide recommendations regarding the care of a patient without formal assessment and communication, have historically been a common practice in medicine. However, when compared to formal consultations, curbside consultations can adversely affect patient care and have been characterized as a “high-risk type of interaction”. According to an article by Burden et al, curbside consultations:

- Often result in the communication of inaccurate or incomplete information

- Alter management advice for patients in 60% of cases

With this in mind, it is essential for students to learn effective communication skills, especially regarding formal consultation practices from the emergency department. The following sections will introduce you to a standardized approach to calling a consultation, common pitfalls of ineffective consultations, and the skills necessary to become an effective physician consultant.

Educational Objectives

At the end of this section, learners should be able to:

- Define the terms consultation and curbside consultation

- Detail the adverse consequences associated with curbside consultations

- Identify components of an effective consultation, including an organizational structure

- Perform a consultation using a standardized model

- List common pitfalls for students in calling consultations

- Describe the skills, attitudes, and behaviors of an effective consultant provider

Framework of an Effective Consultation

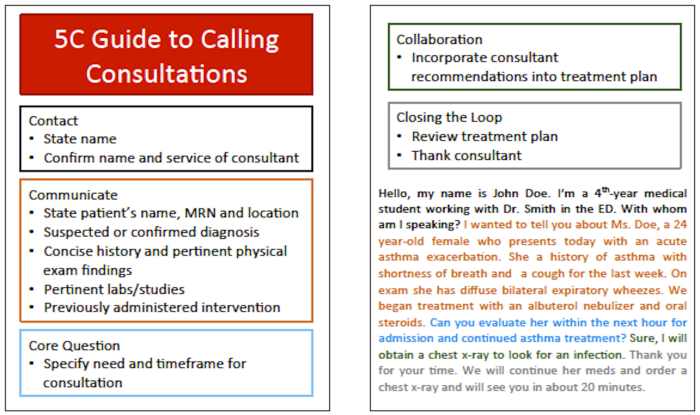

Few models have been formally validated in the literature to aid providers in structuring consultations. The model that has been most rigorously studied is the “5 Cs of Consultation.” This model serves as a framework on which to build a consultation presentation to a consultant physician. The following table lists each of the 5 Cs, as well as describes the specific information that should be included in that section when talking with a consultant.

| CONSULTATION COMPONENTS | SPECIFIC INFORMATION |

| Contact |

|

| Communicate |

|

| Core Question |

|

| Collaborate |

|

| Close the Loop |

|

For an example consultation or an added resource to use during your clinical rotations, print out the following pocket card.

Consultation Examples

The following videos provide examples of a poor consultation and a consultation that follows the 5 Cs framework.

In this first video, notice the items that are absent, incomplete, or ineffectively communicated during the consultation requested by the intern. Additionally, notice the attitudes and behaviors demonstrated by the consultant that negatively contributed to the encounter.

During this video of a poor consultation encounter, you should have observed the following items.

- The intern did not clearly identify the patient’s name, medical record number, or location.

- The intern did not identify the name and role of the consultant.

- The intern did not present many details of the patient’s case, including the working diagnosis and the interventions the team has previously attempted.

- The intern did not ask a specific core question.

- The intern did not establish a timeframe in which the consultant should evaluate the patient.

- The consultant requested a curbside consultation.

- The consultant was very distracted during the phone conversation.

- The consultant made assumptions about the current management of the patient without asking for specific information.

- There was minimal collaboration and a failure to summarize the care plan between the two providers.

In the second video, appreciate how effective the communication between providers is, as many of the above issues have been resolved or improved.

Pitfalls of Consultations

While there is little empirical evidence to support the major pitfalls students encounter in calling consultations, there are a few large mistakes that have are commonly observed.

- Lack of a core question: When requesting any consultation, it is important to have an identifiable question that the consulting service is asked to answer. Generally, it is best to think about how you are going to present your patient’s case, especially the core question, prior to calling a consultation. These questions can be very specific, such as, “I am requesting a consultation from the gastroenterology service to perform an endoscopy on this patient with life-threatening upper GI bleeding.” They can also be somewhat broader, such as, “I am requesting a consultation from the pulmonary service to provide further recommendations for management and outpatient follow up for this patient’s severe asthma.” When formulating a core question, be critical and deliberate in identifying specifically what the consultant service would add to a patient’s care.

- Extensive case presentation: During the conversation try to avoid including information in presentations that exceeds the information needed by the consultant. To overcome this mistake, students should recognize the pertinent information consultant services would request while simultaneously leaving extraneous information out of a presentation.

- Forgetting to close the loop: Before ending any consultation, it is essential to review the immediate next-steps in evaluating and managing the patient while in the emergency department. This serves to remind both parties of their responsibilities and end the conversation moving toward a common goal for the patient. Additionally, thanking a consultant for their time and contribution is professional and important in continuing to enhance interprofessional collaboration in healthcare.

Becoming a Good Consultant

Many students who rotate through the emergency department will ultimately pursue career options in other medical specialties and will serve as consultants to providers seeking their expertise. Therefore, it is important to not only understand the components of how to effectively call consultations, but also the skills, attitudes, and behaviors of effective consultants.

A study by Sibert et al found the following nine items to be important in developing an effective consultant-referring provider relationship:

- Identification of reason for consultation

- Taking into account the referring physician characteristics

- Determining the urgency of the request

- Looking for additional pertinent information

- Specifying relevant communication depending on the urgency of the request

- Providing consultation reports that are easy to read, concise, with fewer than 6 specific recommendations

- Maintaining mutual respect and cooperation

- Clarifying the consultant and referring physician’s respective roles in patient care

- Providing continuous medical education without condescension

Conclusion

Effective interprofessional communication and collaboration lead to safer patient care and enhance workplace satisfaction. Consultation communication skills must be learned and practiced so that ineffective consultation behaviors are not perpetuated. Using the 5 Cs framework when calling a consultation facilitates the effective transfer of medical information between providers on an interdisciplinary team.

References

- Burden M, Sarcone E, Keniston A, Statland B, Taub JA, Allyn RL, et al. Prospective comparison of curbside versus formal consultations. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):31–5.

- Carter K, Golden A, Martin S, Donlan S, Hock S, Babcock C, et al. Results from the First Year of Implementation of CONSULT: Consultation with Novel Methods and Simulation for UME Longitudinal Training. West J Emerg Med. 2015 Nov;16(6):845–50.

- Chan T, Orlich D, Kulasegaram K, Sherbino J. Understanding communication between emergency and consulting physicians: a qualitative study that describes and defines the essential elements of the emergency department consultation-referral process for the junior learner. Can J Emerg Med. 2013 Jan;15(01):42–51.

- Chan TM, Wallner C, Swoboda TK, Leone KA, Kessler C. Assessing Interpersonal and Communication Skills in Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(12):1390–402.

- Cheung DS, Kelly JJ, Beach C, Berkeley RP, Bitterman RA, Broida RI, et al. Improving Handoffs in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;55(2):171–80.

- Eisenberg EM, Murphy AG, Sutcliffe K, Wears R, Schenkel S, Perry S, et al. Communication in Emergency Medicine: Implications for Patient Safety. Commun Monogr. 2005;72(4):390–413.

- Horwitz LI, Meredith T, Schuur JD, Shah NR, Kulkarni RG, Jenq GY. Dropping the Baton: A Qualitative Analysis of Failures During the Transition From Emergency Department to Inpatient Care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009 Jun;53(6):701–10.e4.

- Kessler CS, Afshar Y, Sardar G, Yudkowsky R, Ankel F, Schwartz A. A prospective, randomized, controlled study demonstrating a novel, effective model of transfer of care between physicians: the 5 Cs of consultation. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;19(8):968–74.

- Kessler CS, Asrow A, Beach C, Cheung D, Fairbanks RJ, Lammers JC, et al. The taxonomy of emergency department consultations–results of an expert consensus panel. Ann Emerg Med. 2013 Feb;61(2):161–6.

- Kessler CS, Chan T, Loeb JM, Malka ST. I’m Clear, You’re Clear, We’re All Clear: Improving Consultation Communication Skills in Undergraduate Medical Education. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013 Apr 24;88(6).

- Kessler CS, Kalapurayil PS, Yudkowsky R, Schwartz A. Validity evidence for a new checklist evaluating consultations, the 5Cs model. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2012 Oct;87(10):1408–12.

- Kessler CS, Kutka BM, Badillo C. Consultation in the emergency department: a qualitative analysis and review. J Emerg Med. 2012 Jun;42(6):704–11.

- Maughan BC, Lei L, Cydulka RK. ED handoffs: observed practices and communication errors. Am J Emerg Med. 2011 Jun;29(5):502–11.

- Sibert L, Lachkar A, Grise P, Charlin B, Lechevallier J, Weber J. Communication between consultants and referring physicians: a qualitative study to define learning and assessment objectives in a specialty residency program. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(1):15–9.

- Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004 Feb;79(2):186–94.

- Woods RA, Lee R, Ospina MB, Blitz S, Lari H, Bullard MJ, et al. Consultation outcomes in the emergency department: exploring rates and complexity. CJEM. 2008 Jan;10(1):25–31.